Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

March 3rd, 2004 was a Wednesday, and in its morning hours a brief addition was silently made to the LucasArts.com press release section:

Those two dispassionate sentences proved to have a mondo half-life that in some respects has yet to decay. The phrase “marketplace realities” devolved into cant amongst adventure gamers and remains an entrenched addition to the Mojo vernacular, wheeled out as a jaded bit of seasoning to the coverage of bad news to this day.

The reaction was immediate and unfiltered. That morning, the Mixnmojo staff appropriately sounded off first, publishing a front page editorial that put their raw but considered feelings into words. Reading it again all this time later, one can sense the note of resignation, and with the advantage of knowing what happened next, the dispatch functions as a farewell of sorts from the site.

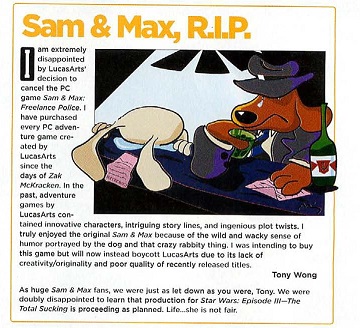

The editorial in its original form ended by listing the emails of Michael A. Nelson, Mary Bihr and Randy Breen, encouraging readers to contact LucasArts directly with their feelings rather than waste time on the feckless gesture of signing the nevertheless inevitable internet petition. Just as ordained was SaveSamAndMax.com, which at the time served as one of the better hubs for all known media related to the title. As Freelance Police had been made available for pre-order on Amazon.com.uk, a number of fans even took the trouble of placing an order for a game they knew did not and would not exist, just for the optics of making the product page rise in the rankings.

In 2004, 32,000 people bitched impotently about a canceled adventure game. Fifteen years later, 1.5 million people bitched impotently about a tits-and-dragons HBO series. I think we all know in our hearts which was the more pathetic.

The simultaneous editorial on Adventure Gamers penned by Evan Dickens was measured and melancholy, and like the Mojo piece takes on the strange character of a divorce being finalized. And like the Mojo piece, the real froth was to be found beneath the article.

Partially preserved in various archived comment chains and forum threads, the howling from the furious multitude was, as an impressed Steve Purcell would note later, “amazing to behold.” Expressing in the same interview that the fan reaction spared him the need to vent public frustration, he also remarked of the fury, “I'd never want to cross those folks.” To the fans’ credit, the tone of their disappointment could be civil, but it would be entirely disingenuous to pretend that it wasn’t often radioactive.

Based on the more extreme comments, it’s hard to imagine what those three inboxes were receiving during the first twenty-four hours - it would have been nice to have gotten a hold of those folks just for their memories of how that Wednesday morning went. At any rate, it’s safe to say LucasArts found itself on the receiving end of a scintillating correspondence or two. Before long, the executives’ emails were removed from Mojo and Adventure Gamers at Ronda Scott’s request. Fans were instead directed to email their concerns to a more general PR address, with assurances that their feedback would be forwarded to the appropriate parties rather than simply discarded. Ronda also responded to the originator of the online petition, who made a point of keeping her informed every time it crossed one of its milestones:

We are aware of the online petitions and I have received your numerous updates. As you can imagine, this was not an easy decision for LucasArts to make. We are reading the many emails being sent in and management is fully informed of the number and sentiment of these messages. I personally very much have always appreciated the support from the many fans of our adventure games and regret that the current games market led to this decision. Rest assured, your voices are being heard.

Purcell, who already maintained a comfortable relationship with the fan base, reached out to Mixnmojo to issue that statement of his own:

LucasArts' sudden decision to stop production on Sam & Max is mystifying. Sam & Max was on schedule and coming together beautifully.

I couldn't have been more pleased with the quality of the writing, gameplay, hilarious animation and the gorgeous 3D world that Mike Stemmle's team has created. The rug has been pulled out from under this brilliant team who've so expertly retooled Sam & Max for the 21st century.

I'm extremely frustrated and disappointed especially for the team who have devoted so much effort and creativity to Sam & Max. It's a shame to think that their accomplishments, as well as the goodwill that has been growing in the gaming press toward this project, will all go to waste due to this shortsighted decision.

Thanks everyone, for continuing to make your feelings known.

Purcell’s comments were welcomed but of course stoked the fire by being the first to advance the corroborated assertion that quality issues did not factor into the decision, upping the level of the tragedy in the fans’ minds. As we’ve seen, Purcell explained in retrospect that he felt the need to speak up on behalf of the team and dispel the natural assumption that the game’s demise was the result of concerns with the caliber of the product itself.

(Purcell’s contention in his statement that the game was on schedule would seem in contradiction with the known delay referenced earlier. Beyond the fact that Purcell wasn’t an internal member of the team, this can be explained by the fact that the schedule had internally been revised to reflect the slip from Spring 2004 to Fall 2004, making the game on schedule under the adjusted, and indeed published – it appears in the GamePro preview – release window.)

Although in less of a position to express it openly, impressed too was the team of the game. All of the developers I talked to confirm that they well remember the outcry, citing it as a silver lining in an otherwise gloomy period at the office. It meant something to them that people on the outside cared. Richard Sun even proudly bought a “Save Sam & Max” T-shirt – part of the avalanche of indignant fan art that ensued – depicting Max wielding a bazooka.

The next day, the Mixnmojo staff took to the front page again to reflect on the hubbub, seemingly surprised themselves by what had been unleashed by their fellow aggrieved, and now past tense, LEC followers. Years of pent-up frustration at the direction LucasArts was taking, and which Sam & Max 2 was meant to relieve, had gone the way of Chernobyl, and a wider audience took notice of the meltdown. “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted” noted Jake wryly, a reference to the fact that a Mixnmojo editorial would not have had such reach under normal circumstances. In fact, traffic to the widely circulated reaction piece was so high that it “owned” Mojo’s humble server (which was comically frail during the best of times); a mirror had to be hosted elsewhere.

Michael A. Nelson passed away in 2017, and we were no more successful in making contact with Mary Bihr than we were with Randy Breen. Consequently, we were unable to obtain comment for the reasoning or pressures behind the decision from the horses’ mouths (if, I feel it’s important to stress, it was even their decision). But Ronda Scott, for all her sympathy toward the fans, has a take that possibly echoed that of the powers-that-be:

I don't remember the specific day but I remember knowing that fans would be disappointed. And, since I knew people like Jake Rodkin and Spaff personally, I think I heard some of that first-hand. But still, to me -- do not take this as the general office sentiment -- it's a company, not a charity. And the fan base was small. PC gaming was on the rapid decline. People outside of companies are allowed to have opinions but the reality of the business was what it was. I felt worse for the devs who had their project canceled and had to have been facing the idea that their genre's time had come and gone.

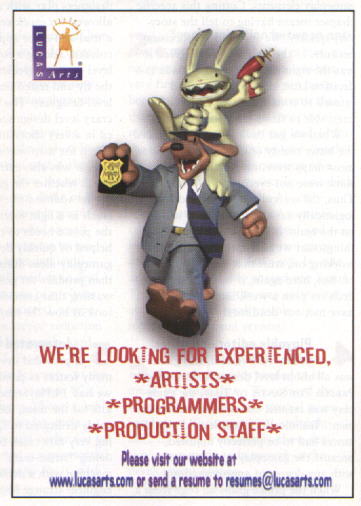

The situation was not without its bleak amusements. As gone over previously, the cancellation had been so sudden even internally that new magazine previews and most of the screenshots showed up only after the fact; all signs point to that long-dormant marketing machine being just about to hit full swing when the axe fell. Appallingly, one of those fashionably late April magazines included a recruitment ad for LucasArts – starring Sam and Max!

While the event came and passed in a wink of time for gaming media as a whole – sites like Gamespot or IGN did little more than dutifully acknowledge the press release as a news item – and most of LucasArts’ modern audience went right back to anticipating the release of Obsidian Entertainment’s Knights of the Old Republic II (which was rushed out to make the holiday season, though unlike with Armed & Dangerous this wouldn’t hurt sales), the inconsolability of the vanquished game’s audience would not be so fleeting. In the silo’d corners of the internet where that audience made home, the madness continued for quite some time, and an explosion of deranged creativity resulted.

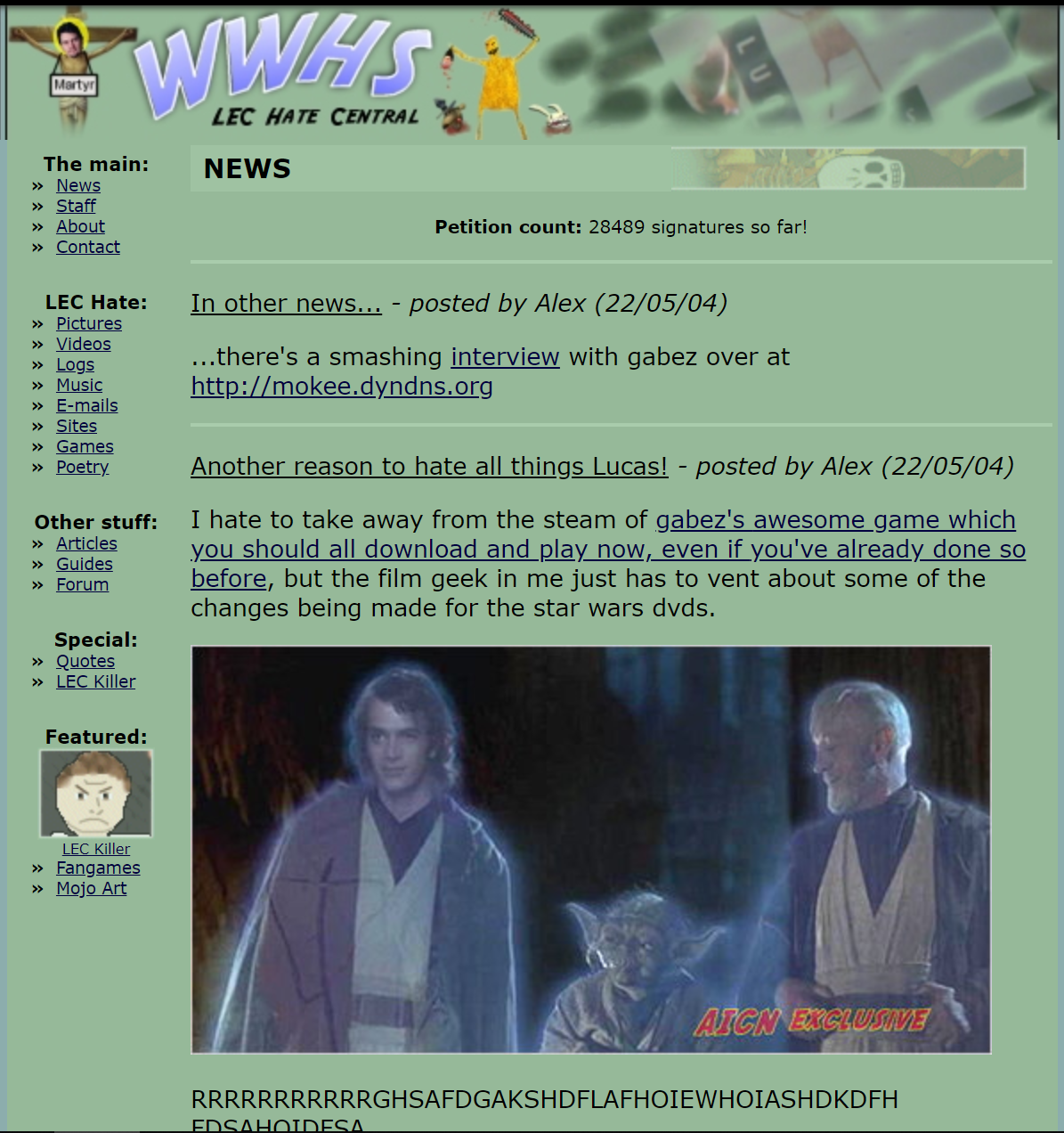

The most striking example of this was a web site called The Wibble Wobble Hat Stand. Originally created by Mixnmojo staffer Gabez years earlier as a self-contained adventure fan site, it was reinvented in the wake of Sam & Max 2’s cancellation to become a repository for LucasArts “hate art”. Most of this took the form of crudely Photoshop’d images or slaphappy videos (“Yeah, I used to love playing with Truespace,” recalls staffer elTee with unwarranted shame), but there were some genuinely consummate entries.

The crown jewel was a fan game that Gabez himself impressively threw together in The Games Factory. (And if you know what that is, you’re very old indeed.) Called LEC Killer, the sublimely ramshackle, mission-based game has you controlling an unhinged LucasArts fan who infiltrates the studio to exact vengeance. To give you an idea of the tone this masterpiece is pitched at, Simon Jeffery (who was often jokingly referred to as a martyr on Mixnmojo after he stepped down as president) is depicted as a crucified Christ figure, while Mike Nelson is a corporate suit in a Darth Vader helmet. Do not hesitate; play it now. It won’t necessarily run on your PC, and if it does you may encounter showstopping bugs, or for all I know a kernel rootkit. In other words, it’s still more stable than RTX: Red Rock.

So, okay, the tsunami of bile that raged throughout the spring and summer months of 2004 was often lacking in perspective and could be more than a little juvenile, but the pain behind it was authentic. And for all its absurdity, the fever pitch demonstrated something kind of poignant. After all, that sustained level of emotion is only possible from a crowd that deeply cared; heartbreak is never that ugly unless the love was real in the first place. What the out-of-hand reaction underlines is that it was the most loyal, passionate and entrenched fans that LEC decided it was willing to lose out of temporary convenience. While more detached analysts would go on to uncritically label later LEC transitions or its official closing as “the end of an era”, it was really this moment that the page was being turned. Everything that came after was just the slow process of powering down.

Perhaps this is a coerced comparison, but I remember experiencing déjà vu years later when Conan O’Brien was deposed by NBC as the fifth host of The Tonight Show. There was a similar groundswell from outraged fans who turned Conan into folk hero in the online sphere, accompanied by an outpouring of unhinged fan art. There were similar themes between the two stories, including the framing of the matter as mainstream versus niche or establishment versus fringe, and the significance of the web as a platform of rescue after traditional outlets had gone sour for the respective talents. As with Sam & Max 2, the actual subject (an adventure game, a talk show) may have been a silly thing to focus so much energy on, but there was something visceral about the loyalty on display, and you had the sense of a certain audience departing along with the talent LEC/NBC was cutting loose.

A number of longtime Mixnmojo staffers moved on from the site in short order. This included Jake Rodkin, James ‘Spaff’ Spafford, Andrew “telarium” Langley, Doug “tabacco” Tabacco and Dave “Metallus” Eggers. Together with a few fellow game journalists, including Adventure Gamers regulars like Marek Bronstring and Chris Remo, they founded Idle Thumbs, a gaming webzine that eventually morphed into a respected podcast network. Later on, and in some cases simultaneously, these folks would be working in the industry they once wrote about; in two years’ time, most of the Mojo expatriates would be part of the staff at Telltale Games. Today, Jake works at Valve while Spaff has become the Ronda Scott of Tim Schafer’s Double Fine Productions.

For those that remained, there was an uneasy question hanging over this web site. “What are we still here for?” Mixnmojo was ostensibly a LucasArts fan hub, but the more-dutiful-than-engaged coverage of non-original games had increasingly been posturing, a way of killing time while waiting for the real products of interest – particularly the one snatched out of our hands at the last minute. Aside from the then still-forthcoming release of Double Fine’s Psychonauts, there wasn’t much on the horizon for Mojo to feign excitement about for the remainder of 2004, and the more distant future didn’t seem any more awash with hope to our permanently jaded eyes.

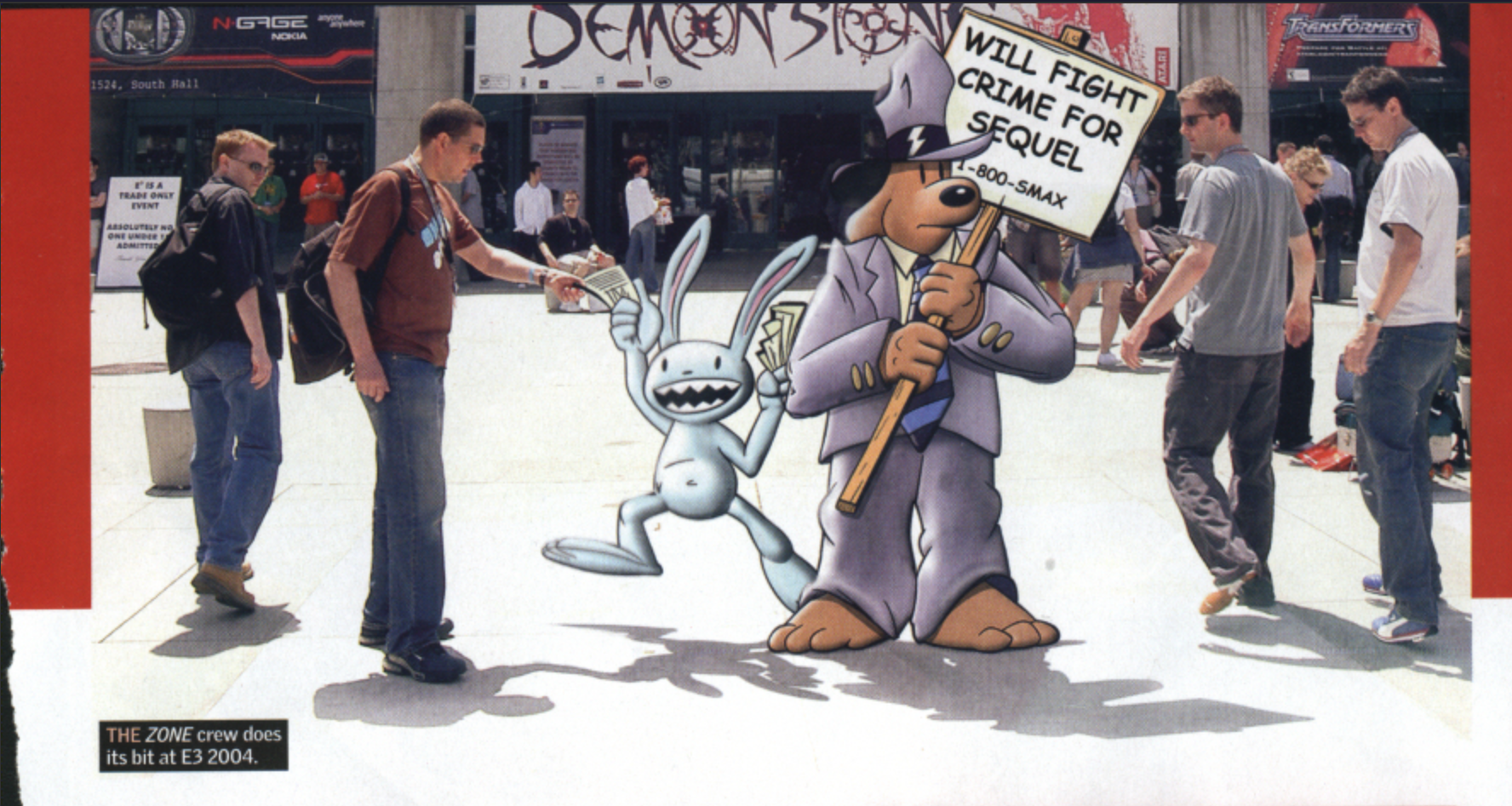

A very awkward E3 2004 did see LucasArts unveiling Mercenaries, a third person shooter by Pandemic that had been rumored in the preceding months (under the working title Free Agent) and might have been a more intriguing product under other circumstances. But considering that it essentially looked like Armed & Dangerous Minus and the bombshell was a few short weeks in the rearview mirror, we weren’t much in the mood to work up enthusiasm for an also-ran shooter. Interestingly, though, someone at Pandemic or LucasArts saw fit to sneak a reference to the Sam & Max debacle into the game’s cutscenes.

(In an almost laughable marathon of bad news, Psychonauts received a cancellation of sorts itself at the end of March 2004 when Microsoft opted to drop it from its line-up. Fortunately for the self-owned platformer, it would find another publisher six months later in Majesco Games; it was finally released after a particularly lengthy development in Spring 2005. At the time of this writing, its much-anticipated sequel is scheduled for release in 2021. In an O’Henry twist, it is being released by Microsoft Studios after some publisher switches of its own.)

A particularly bemusing episode did keep us occupied for a while and is an obligatory footnote in any history of Sam & Max 2. Toward the end of 2004, out of nowhere, a German-based publisher sprang forth and immediately caused a stir with reckless and provocative insinuations about the destiny of the shelved Sam & Max 2 assets. The company was called Bad Brain Entertainment, and its founder and CEO was named Wolfgang Kierdorf.

Despite no games industry background, Kierdorf made loud noises to the effect that he was plotting to buy Sam & Max 2 from LucasArts so that he could get it finished himself. Simultaneously, he unveiled a slate of supposedly upcoming in-house adventure games, and signed on as the publisher for Bill Tiller’s LucasArts-style adventure A Vampyre Story.

It took no longer than January 2005 for the bad joke to get its punch line. The Sam & Max 2 talk proved to be only that, Bad Brain and Tiller later parted ways when it was clear that the fly-by-night publisher didn’t actually have money, and, oh yeah, that line-up of games was soon admitted to having been made up on the spot.

The whole thing was a surreal bit of commotion for a fan base that really didn’t need to be jerked around any more than it had been, as Jake expressed in an Adventure Gamers forum thread reflecting on the weirdness. Once the frustration died down, however, the comedy of the situation found a certain cynical appreciation, and to this day Kierdorf is still a fondly remembered character in the annals of Mojo lore. A situation that is oversold or otherwise not as it seems might still occasionally be described as a person or company “pulling a Kierdorf,” and despite any accusations of insanity we are inviting by admitting so, we hope to warm our hands by the fire of that particular memory for many a year to come.

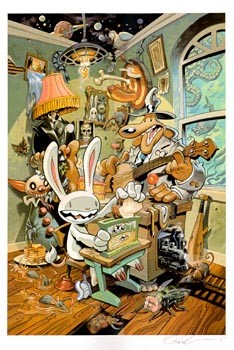

The eighteen-month period between the cancellation and Telltale’s turn with the Sam & Max license wasn’t entirely without event for Purcell’s characters outside of the interactive space. Very quietly, the web presence of a Gary Winnick-founded company called Tantrum Entertainment started selling a pair of signed, poster-sized Sam & Max art prints. A gorgeous, deranged moment of Sam and Max in their office was captured in a piece dubbed “Something’s Not Right Here,” while the other was a blow-up of an old Sam & Max strip from an issue of The Adventurer that parodied the LucasArts’ western shooter Outlaws.

Winnick and Purcell, the latter operating under the label “Spudvision” (which would later be the name for the artist’s web presence), were apparently plotting a broader collaboration through the startup, including some sort of comic collection, but whatever they were up to never actually happened. Nevertheless, those posters were real enough and look great on my wall, so I consider the lapsed affair a net profit.

If the objective was saving Sam & Max 2, the ultimate impotence of the fan outcry came with a degree of self-awareness. A proposed picketing outside of LEC was ridiculed out of existence; a few giggles were had over a facetious heist pulled at E3 2004 (which was attended by a cross-section of Adventure Gamers and Mixnmojo staffers) in which a near-microscopic Max sticker was slapped on the wall of the LucasArts display booth; the attitude of the fan art was as defeatist as it was furious.

The late Randy Sluganski of Just Adventure wrote an op-ed arguing that Sam & Max 2 was the most important game of E3 due to the fallout it caused and the specter it raised in the corridors of the expo, but at the end of the day, while we suspect the online furor was a good deal more than any of the muckety-mucks at LEC had bargained for, the lack of action taken in response is proof enough that they were unfazed by it.

But while the fans had no hope of convincing LucasArts to reverse its decision, and while the embittered jangling they set off did not resonate nearly as much in “the real world” as in their margins of cyberspace, neither was the noise they were making happening entirely in an echo chamber. As indicated, their voices were being heard clearly enough by those perhaps who needed to hear them most – the developers who had been working on the game.

Among those was a subset for whom the fan response was an inspiration to try to accomplish themselves what LucasArts in its stultified final decade lacked the vision to follow through on.

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo