Part 10: Telltale Now

The cancellation press release concluded with the statement that “There are currently no plans to reduce staff.” It took as long as seven weeks for the mass layoffs to commence. Affected personnel included Sean Clark, the latest veteran (in his case, of fifteen years) to depart the company. Among the Freelance Police team let go was Randy Tudor, who remembers that he was out the door within "only a couple of days, I think," and that the workforce reduction was carried out with roughly the amount of grace you'd presume. "After the cancellation, I was again assured that my job was secure, but I think I knew by then this was bullshit. When the axe came down, we were only given a short time to pack our stuff before being escorted from the building."

A new president, Jim Ward, was appointed in May, and as would become tradition with regime changes, further layoffs followed and would characterize the rest of the year as LEC transitioned to its next phase of bad faith course correction. The history of LucasArts from this point forward, however, is beyond the scope of this article.

Some employees jumped before being pushed, but voluntarily or not key members of the Freelance Police team dispersed quickly after the game collapsed. Exceptions included Mike Stemmle, who stuck around a few months longer to write dialog for Star Wars games until his number was called, and Steve Chen, who had only just returned to LucasArts for Freelance Police after having worked on the initial two years of Psychonauts’ unusually long development cycle. (Chen was part of the original band of Grim Fandango vets who had followed Tim Schafer on his new venture.) Summarizes the designer: “LucasArts was essentially rebooted from the ground up."

Dan Connors, Kevin Bruner, and Troy Molander (another LEC disbursal who seems to have kept a lower profile) founded Telltale Games in April 2004 as CEO, CTO and COO respectively. Among their first employees were Brendan Q. Ferguson, who had worked as a programmer/writer/designer on Freelance Police, and Graham Annable, who served as the studio’s first Creative Director. The startup came to our attention in June 2004 with the launch of its web site. In its initial form, it consisted of little more than a running staff blog largely authored by Ferguson, and the following self-description:

Telltale Games has heard the cry for entertaining, visually appealing, character-rich, cinematic games and we're preparing for a rapid response!

Telltale's extensive game production experience has culminated in technologies and production processes that enable Telltale to build and release several quality game "episodes" per year, bringing licenses from notable authors, game designers, comic books, and cartoons to the on-line audience.

We're putting our years of experience into serving short helpings of mind-bending puzzles involving your favorite characters, and introducing new ones you're sure to love. And at a value which will have gamers, from the hardcore to the casual, coming back for more! Combining our story-telling, puzzle-crafting talent with our proprietary technology, we'll deliver the interactive, cinematic experience you've been longing for!

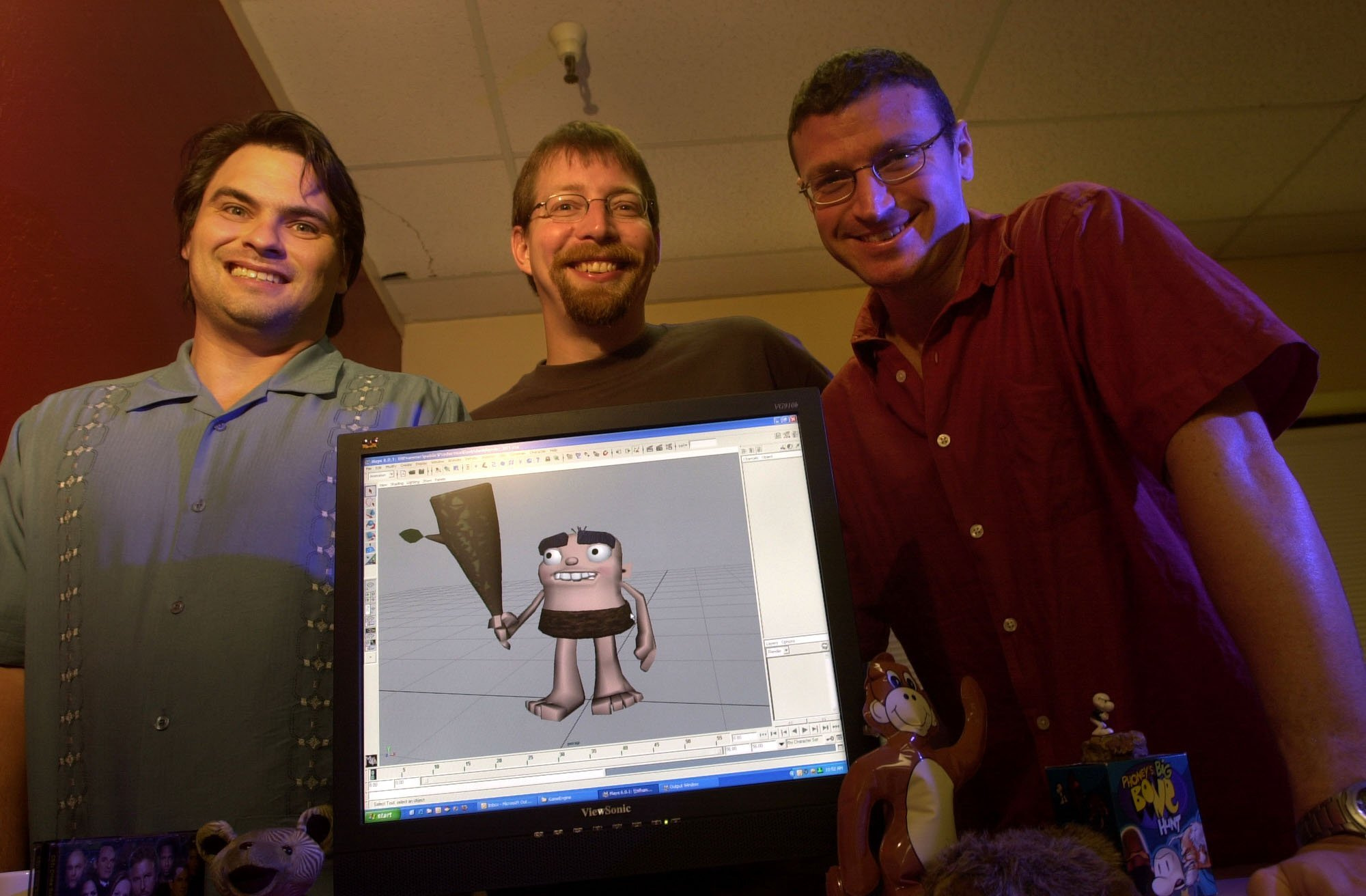

The first real sense of Telltale’s vision came in October when Adventure Gamers ran a profile of the up-and-coming studio. Clear in its goals from day one, the oven-fresh company (possibly six men at the moment) summarized its aspiration to become the games industry equivalent of a television studio. Although they made no Kierdorf-like promises, the inevitable speculation that Telltale could eventually make new Sam & Max games (as opposed to somehow trying to finish Freelance Police, which was LucasArts-owned even if the characters were not) erupted immediately. While largely a fan-generated concept, the idea of Telltale as a kind of successor studio to LucasArts was encouraged by their continued hiring of many LucasArts veterans as they staffed up.

Wish fulfillment didn’t prove to be outside of the studio’s capacity. After the rights to Sam & Max lapsed back to its creator in May 2005, Steve Purcell quickly hammered out a deal with Telltale, the personnel of which he knew from experience he could trust with the characters. The agreement was announced on September 15th, 2005, and aside from the predictable uncertainty about digitally-distributed episodes voiced by the fiercely traditionalist adventure crowd, there was much rejoicing.

While fans awaited the games themselves, they were kept placated with new merchandise – including a T-shirt design by Purcell which debuted the characters’ now hoodless DeSoto squad car – as well as a new Sam & Max web comic published through the Telltale site. There were also Telltale’s first few releases to busy ourselves with.

Unsurprisingly, it turned out that Telltale had designs on Purcell’s license from the start. That Sam & Max was not their debut game was largely a matter of waiting out the expiration date on LEC’s hold on the license while getting their technology, specifically the propriety engine that would power all of their products (The Telltale Tool), off the ground. Telltale’s first release was a poker simulator called Telltale Texas Hold’em (February 2005) – effectively a test of their toolset that they opted to make public – followed by two episodes (the first in September 2005, the second in April of 2006) of a regrettably abandoned adaptation of Jeff Smith’s Bone comic that properly unveiled their 3D adventure engine, which among other things gave us a glimpse of what the gameplay of Freelance Police might have been like.

Though digital self-publishing was Telltale’s focus, they also signed on to become Ubisoft’s latest developer of the CSI game franchise, which gave them access to their first high profile license. CSI: 3 Dimensions of Murder would be released on store shelves by Ubisoft in March 2006. Despite being a retail game, it is structured into five cases (as were the previous, non-Telltale CSI games) and was developed on much the same sort of production schedule as the studio’s own episodic releases.

With their initial games, it wasn’t just their engine that Telltale was trying to perfect, but their business model. The lessons learned from Bone in terms of the episodic strategy (game lengths, price points, and the release schedule were the major factors still being figured out) would be brought to bear on their most awaited project. It was with Sam & Max that they would debut the fundamentals they would become known for, namely the idea of serialized games as TV-like “seasons” released on a monthly (or in any case, reliable) basis. At the time they were calling their delivery system Telltale Now, and it proved to be an enormously successful and influential solution to making narrative games for properties that were considered too niche to flourish at retail. Though most people today associate Telltale with The Walking Dead, Batman or The Wolf Among Us, the vanguard was Sam & Max.

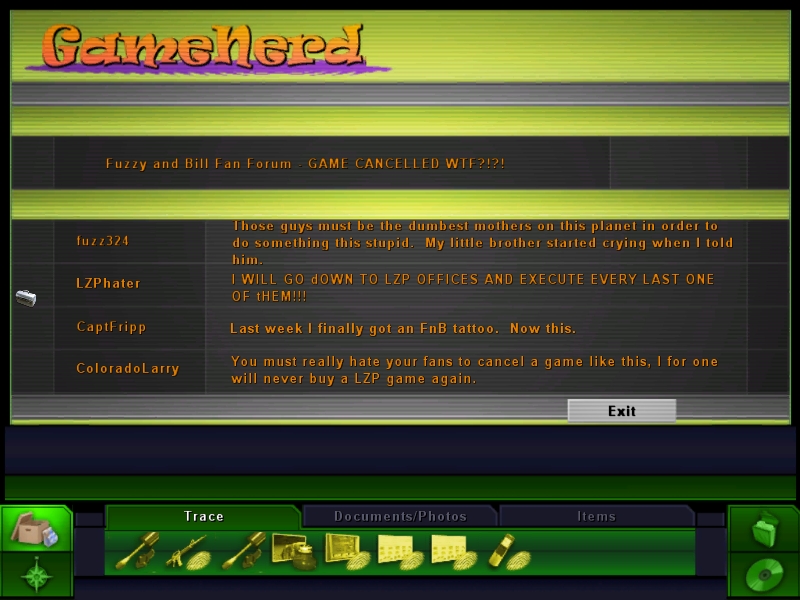

As much as Telltale was about moving forward, it is interesting how present the ghost of Freelance Police remained in its offices during those exciting early years. The most obvious artifact of this is the second case of CSI: 3 Dimensions of Murder, in which the player must investigate a homicide at an E3-like trade show. The storyline is transparent and shameless in its referential commentary, even featuring analogues for its own developers. The marketing character “Maya Nyugen” is certainly named after Telltale (and formerly LucasArts) artist Mai Nguyen, and the game designer character “Craig Landers” is clearly a play on Greg Land, another LucasArts defector who was the project lead on the CSI games at Telltale. The case’s story refers to a niche but beloved comic book franchise called Fuzzy & Bill which was abandoned by a fictional game studio in favor of the more mainstream Gutwrench III. It’s kind of amazing how unsubtle the whole thing is.

No strangers to self-referential humor themselves, Sam and Max would comment on their recently bumpy past in their own Telltale episodes. In the series’ ubiquitous office location, atop a filing cabinet is a cardboard box dated 3-3-04. (“I remember that case,” says Sam if the player interacts with the background prop. “Particularly gruesome.”) In the first season’s second episode, Max refers to the level of the duo’s popularity as being of an “internet petition” pitch, and in the second episode of Season 2, Sam finds “a fully playable beta of Sam & Max Freelance Police” amidst a lost and found pile on Easter Island. Whatever coyness those winks might represent evaporated completely by Poker Night 2 (2013), in which Sam, acting as an acknowledged vessel for Stemmle himself, can be heard to blatantly rattle off the plot synopsis of Freelance Police in close to a point-blank way, with only some substituted nouns to stave off litigation. Sam’s divulgences can be found as a laid out narrative here.

Telltale would debut their first Sam & Max episode in October 2006, and the first public glimpse of their take on the license would come in the form of this E3 2006 trailer:

It’s interesting to compare this trailer to the one LucasArts debuted only three E3s prior. That Telltale’s project had a lower budget was evident, and this first look suffered a little bit from the impression of imitation actors by a fan base that had not yet gotten accustomed to the new voice artists.

(To get into the weeds a bit on the VO talent: Both characters were voiced in this trailer by David Nowlin, a Telltale mainstay since portraying the protagonist of Bone. Nowlin would remain Telltale’s interpreter of Sam for the full duration, while Max underwent some recasts, first with another Telltale go-to, Andrew Chaikin, often credited by his stage name Kid Beyond. Chaikin can be heard as Max in the pilot episode – Culture Shock – only, as temporary health issues impacted his availability in the non-adjustable episodic schedule. He was thereafter replaced by William Kasten and then Dave Boat, while Chaikin would remain otherwise ubiquitous in Telltale’s catalogue until the very end, Sam & Max supporting characters included. As for why Bill Farmer and Nick Jameson were not tapped, it is believed that it was too difficult or expensive for the modestly financed Telltale to secure them for the sustained schedule an episodic game requires. Telltale relied predominantly on local, Bay Area talent for their games.)

Telltale would go on to make three seasons worth of Sam & Max games, and it was universally acknowledged that they improved with each outing. Some would argue – myself included – that the final season, Sam & Max: The Devil’s Playhouse, was the crown jewel of the Telltale catalogue and up there with the best of LucasArts’ graphic adventure games. Telltale’s happenstantial love-bomb to alienated LucasArts fans would peak with another revival, Tales of Monkey Island, among a clutch of other endearing niche properties like Homestar Runner. (Technically, the fifth Monkey Island game was the only revival of LucasArts IP at the hands of Telltale, since LEC was never the owner of Sam & Max as a property – Lucasfilm only controls Sam & Max Hit the Road and their unfinished sequel to it.) It was during these seemingly halcyon years that many former Mojo staff, including Jake, Metallus, telarium and tabacco, served out their Telltale stints.

To delve any further into the history of Telltale Games would require a devoted article of comparable scope to this one. For similar reasons, I must elide coverage of the ultimately unfulfilled promise LucasArts was faintly showing during this period. (Tales coincided with “special edition” releases of the first two Monkey Island games produced by LucasArts itself.) But I do want to work in, as an amusing aside, the fact that the Lucasfilm web site at one point mistakenly included a screenshot from Telltale’s Sam & Max game, rather than their own, as part of a snapshot of the game studio’s proud back catalogue.

For the purposes of this article, I wanted to underline two things about Telltale. For Mixnmojo, the arrival of the studio onto the scene was not just a boon, but a lifeboat. With pretty much nothing to cover out of LucasArts after 2004, the site entered (and perhaps never left) a clumsy period of identity crisis that included shifting and diversifying its targets of coverage, all with the disadvantage of the original staff having split for greener pastures.

Telltale was in a way the centerpiece of the evolving Mojo charter, though the releases of Double Fine, Autumn Moon (Bill Tiller’s studio), Crackpot Entertainment (Larry Ahern and Mike Levine), and Ron Gilbert were equally crucial justifications for keeping the plane flying. In simple terms, Mixnmojo reconfigured from covering LucasArts to games made by LucasArts vets that had earned our interest, but to this day I believe it was Telltale’s reliably regular activity that kept us engaged enough to see this transition through. I’m not convinced we would have held together otherwise.

The second point is the level of influence that Telltale had on the overall resurgence of the graphic adventure that happened in its wake, as well as on episodic gaming. That influence is undisputed, its extent less so. Mike Stemmle would be on the modest side of that debate:

I don't think it's going far enough. I'd also like unwarranted credit for personal computers, Candy Crush, and pumpkin spice lattes.

Seriously, the digital download revolution was going to happen. I'm just happy that Dan and Kev had the foresight to ride the wave.

That is likely the truth, though it is also true that, in the words of Kevin Bruner, Telltale was “a direct reaction to the cancellation." But the point is taken: As clear as the case may be for an unambiguous impact where Telltale’s founding or little Mixnmojo is concerned, Freelance Police’s broader influence is harder to nail down. It’s probably going too far to suggest that Telltale was single-handedly responsible for the genre’s humble comeback of sorts that the last fifteen years have seen fit to grant it, but the studio’s role in demonstrating that the online space combined with alternative business models was the genre’s salvation was...let's settle on non-negligible.

And while Telltale did not crowdsource its games, the Kickstarter craze that this last decade and a half has also seen is surely an extension of this revolution. The runaway success of the Double Fine Adventure Kickstarter from 2012 is seen, with good reason, as the most influential example amongst countless successful crowdfunding campaigns for independent adventure games that followed, whether they be remakes (Leisure Suit Larry, Shadowgate) or original games from genre icons (Ron Gilbert’s Thimbleweed Park, Bill Tiller’s Duke Grabowski) as well as from plucky indies. But it wasn’t the first, and neither did it happen in a vacuum.

The acceptance of crowdsourcing as a viable method of financing niche entertainment was a critical but individual part of a broader (and continuing) epiphany that occurred about how narrative games fit into the changing media landscape – a landscape where middlemen can be more easily obviated, and where the audience and the artists aiming for them can transact more directly. Apparently, it’s a world more suited to adventure games than the less flexible structures of the nineties and early 2000s, and Telltale must be credited with helping to make that undeniable.

In the case of Sam & Max, one of the many things that Telltale provided was an end of story, both for fans and developers, after LucasArts had so callously hit the pause button on the duo’s exploits. I asked Stemmle, who would join up with Telltale in time to participate in their third and final Sam & Max season, whether he felt a sense of closure at being able to reunite with the characters.

Sooooooo much closure. Closure the likes of which cannot be imagined. I even got to use my rejected love theme from Hit the Road. Now THAT'S closure.

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo