Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

As challenging as 2003 may have been for other internal projects, Sam & Max 2 was chugging along, seemingly impervious to or walled off from the catastrophes that were plaguing its sister productions. As Mike Stemmle put it in the first proper retrospective published about the game, from PC Zone’s October 2005 issue: “I can honestly say that it was the smoothest project I ever worked on. Of course, nearly every seat was filled by hot-shot-game-building veterans, so that probably had something to do with it.”

With the superlative in check, the game’s director repeated this sentiment for Retro Micro Games Action Magazine, which ran a nicely crafted retrospective on Full Throttle 2 and Sam & Max 2 in its April 2010 compendium: “Speaking purely from the development perspective, Freelance Police was definitely one of the smoothest projects I was involved with at LucasArts.”

The esteem in which Stemmle held his team in retrospect is consistent with how he presented them in contemporary Sam & Max 2 coverage. The first meaningful preview of the game came in May 2003, in conjunction with E3 and the release of the game’s first and only trailer. At that time, the project was preparing to shift from pre-production to full-swing production, so representative screenshots were still far off. But in his chat with Marek Bronstring of Adventure Gamers, Stemmle nonetheless offered the first material tidbits about the game. He helpfully assigned names to that dream team, some of whom would end up joining or even founding Telltale Games a year later:

Can you introduce us to some of the people on your team?

I'd be happy to. Our lead artist is Derek Sakai, recently returned to LucasArts after an extended hiatus in the Great White North. Our programming effort is being spearheaded by Kevin Bruner, a crafty veteran who knows enough to keep me as far away from the code as humanly possible. Graham Annable is our lead animator and another LucasArts veteran, but he's less crafty and more wily. On the scene designing/mini-game implementation/making sure the game comes together front, Steve Chen has returned to LucasArts from parts unknown to ensure that the finished product is actually fun. Our music is being composed by Mark Griskey, ably abetted by our sound designer, Nick Peck. The whole shebang is being produced by Dan Connors, who's contributing much, MUCH more to this project than his usual bang-up organizational skills. And of course there's Sam and Max's creator, Steve Purcell, who's been feeding us story ideas, cut-scene dialogue, character concepts, free posters, and all-around creative guidance whilst simultaneously holding down a day job at Pixar.

It's a seriously butt-kicking group of folks.

What type of engine are you using for Sam & Max: Freelance Police?

It's a point-and-click adventure game engine that's been cobbled together from parts of engines that are already lying around LucasArts. There's a little bit of the new Full Throttle game in there, along with a hint of Gladius, a smidge of RTX, and even a touch of Obi-Wan. We're trying really really really hard not to create "The Wheel, version 5.0" on this project.

It is retrospectively significant that this E3 2003 preview contains not a whiff about digital distribution. Although this could simply have been a strategic withholding of information, it may speak to the reality that the details were very much up in the air. Stemmle tells us today, “Dan and Kev were definitely enthused about the prospects of digital distribution from day one. My recollection is that it always remained an option right up until the cancellation date.” That it merely “remained an option” despite having been so much part of the project’s inception would suggest that LEC was never entirely sold on the idea.

If the unproven nature of an internet-based release made it a little too radical for LEC’s comfort, the premise of adventure games moving toward bite-sized episodes was not without precedent. Ron Gilbert himself had toyed with the idea in the early 90s (absent the online component, of course), and even then Sam & Max was identified as being particularly well-suited to punchy, digestible adventure games that might be sold at the checkout counter of a retail store.

Steve Purcell recalls briefly brainstorming ideas with Dave Grossman – who would eventually get to work with the characters at Telltale a decade later – for a sequel along these lines shortly after Hit the Road, while Gilbert’s instincts that the genre’s survival would be improved on a smaller scale led him to produce adventure games aimed at children under Humongous Entertainment, which he co-founded with Monkey Island 2 producer Shelley Day. In 2001, the same pair founded what was essentially a successor studio, Hulabee Entertainment, which came closer to bringing Ron’s initial vision to fruition: Among the short-lived studio’s catalogue was Moop and Dreadly in the Treasure on Bing Bong Island, a six-chapter adventure game. Given Hulabee’s web-based tilt, it’s no great leap to imagine that Gilbert was heading for the same conclusion as the Sam & Max 2 team, and at around the same time.

Even after picking the brains of several Freelance Police team members, the details of how the digital distribution idea began and how it evolved remain somewhat murky to me. Kevin Bruner credits Dan Connors with being the person who proposed the idea, and appropriately enough it does seem to be the future founders of Telltale who were most keenly aware that this was a promising and perhaps necessary route for adventure games to merge onto if they hoped to become a going concern at LucasArts once more.

Lead Designer Steven Chen similarly recalls this forward-thinking aspect of the project as elemental, stating bluntly that "Freelance Police was designed to be an episodic game that could expand beyond what was the initial game." In an interesting contrast, the programmers, artists and animators who spoke to me seemed to be fairly oblivious to the downloadable angle, with Graham Annable, Derek Sakai, Jonathan Sgro and Richard Sun all telling me that they were removed from those conversations. Aside from the obvious artifact that was the game’s structure of six smaller “cases” (it’s unclear if “episodes” had entered even internal parlance at that point) as opposed to one full length adventure game, the manner in which the digital pitch would actually manifest come release date was very much a matter of debate until the last day the project remained in production.

The compromise that Freelance Police was headed toward was for it to be both a retail release and digitally distributed simultaneously (a common strategy now, but certainly not then), with the pipeline that was being built for the latter set to be leveraged, it was hoped, for post-release content. The potential for this was open-ended to the point where the establishment of a full-on Telltale-like delivery system might have been eventually possible within LEC itself. Says Connors:

Digital Distribution was a longer term play that likely would have positioned LEC well. It’s a bummer because we were working on a cool streaming download system, with add ons and updates. We were also looking at other channels. I was trying to get Rogue Squadron on to Real Arcade as a proof of concept.

The fact that LucasArts ultimately couldn’t bring themselves to embrace the digital frontier and equivocated with the one foot in, one foot out approach was an issue of, as Connors puts it, falling short of critical mass:

There was always debate about everything because of the number of people and departments that needed to rethink how things should be done. I think the thing that could have saved Sam & Max 2 [is] if we finished and shipped Episode One before the other episodes were done. This became standard at Telltale but at LucasArts they weren’t comfortable unless three episodes were in the bag.

It’s noteworthy that all of this debate was entirely to do with the game’s distribution; the corollary is that the building of the game itself wasn’t a very troubled process. The actual production of Freelance Police was, going by Stemmle’s portrayal, pretty smooth sailing. He doesn’t stand alone. Jonathan Sgro told me much the same thing:

It was smooth. I owe that to Kevin’s technology plan, Dan’s production plan, and a team of great artists. Kevin and I learned from our past projects at LucasArts and focused on tech that was user friendly and built for rapid/smooth development. S&M 2’s downfall was purely due to upper management’s perception of market place realities.

"Yeah, I would have to agree with that," says Randy Tudor. "Things were progressing smoothly and the team was fantastic. If there were internal problems, I wasn’t aware of them." And so the oft-termed “oasis” that was this project was fully exploited by a well-curated team eager to flex their talents on an assignment so different from anything else at the studio. Purcell’s universe was more than just not-Star Wars; it was a vibrant world that reveled in madcap insanity - a sandbox where anything goes.

The work by Annable and his crack team of animators which included Joe White, Yoko Ballard, Mike Dacko and Karin Nestor, seemed to particularly delight the team, and more than one developer had a recollection of a specific animation that made them laugh. Stemmle recalled:

During one meeting, the artists were showing off the latest animations and characters from an episode revolving around a 'Burning Max' festival, which featured, among other things, copious nudity. Unbeknownst to me, one of the many buck-naked models crafted by our cheeky modelers was none other than yours truly. Now, back then I was a lot of things, but an attractive naked man I was not. Soon afterwards, a video clip of my cartoonish naked form doing a sultry dance on the grounds of the festival was making its way through the halls of LucasArts. Although I've since tracked down and obliterated most of these videos, I keep one on my hard drive at home as a reminder to me to stick with my diet.

(Stemmle’s nonconsensual participation as an NPC would have continued a tradition of sorts, as Stemmle and Clark made voice cameos in Hit the Road and visual cameos in Monkey Island 4, where a pair of squabbling chess players were designed as caricatures of the project leaders.) Annable fondly remembers a mid-air somersault by Max created by Yoko Ballard, and Purcell described the routine of being emailed animations by the art team as akin to “receiving a little present every day.”

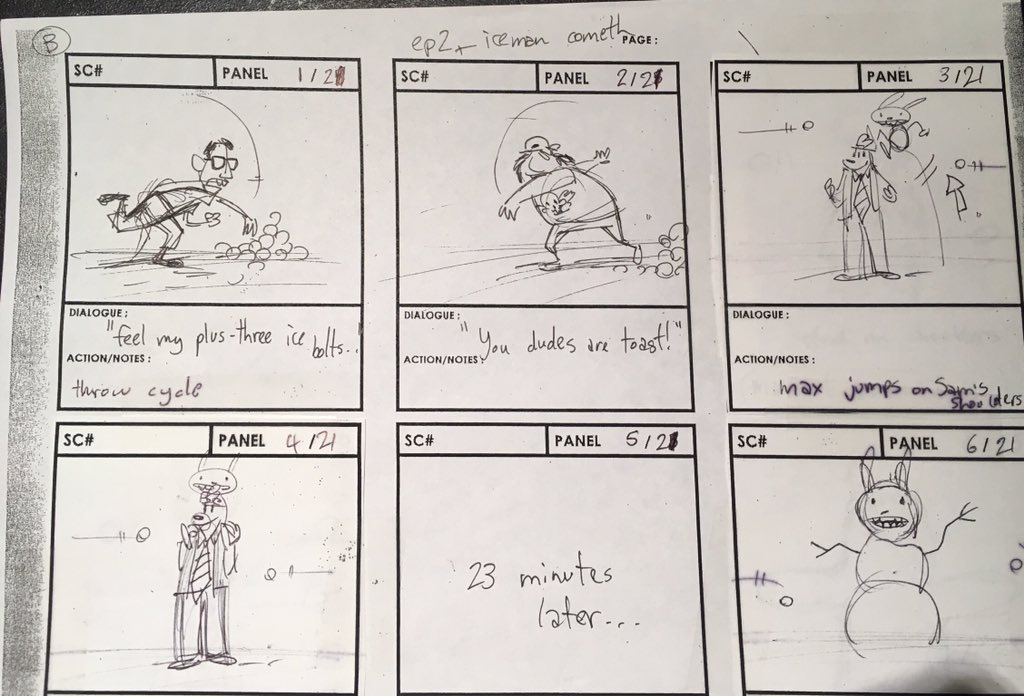

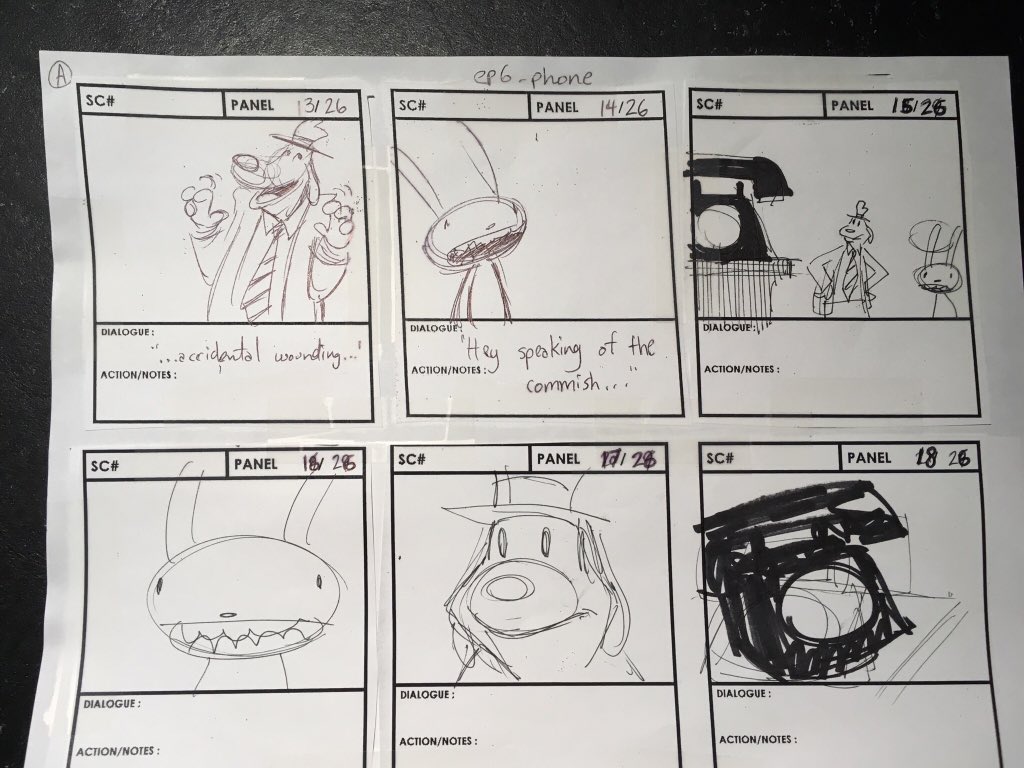

The preceding reference to a Burning Max festival is a tantalizing indication of the kinds of locations – always a hoot in a Sam & Max game – which would have been in store for salivating fans. Like most everything else, info about the storyline(s) of Freelance Police only made its way to the base in dribs and drabs, the majority of it after the cancellation, but we know enough by now to get a high-level idea of what the six cases were about. Here’s what Stemmle remembers of the plot today:

Basically, there were going to be six separate stories with a burbling backstory that would come to the fore in the final chapter. The big story involved the return of the ancient marauding Subarctican civilization (giant Penguins), whose high priestess (a librarian named Penelope Gwinn, get it?) would sacrifice the Chosen One to awake them from their eternal slumber. In a twist, the Chosen One would be Sam, rather than the expected Max.

The opening episode featured a dance off at a high school gym where all the kids started mysteriously acting like extras in West Side Story, as well as a mini-game that could've served as a prototype for Rocket League.

One episode had a Zamboni fight.

One episode took place at a Burning Max festival, and featured the Freelance Police's arch-nemeses, Mann and Sachs.

Another episode brought the Rubber Pants Commandos into play, as they sought out former child star Il Gato Grosso, who was stealing all the city's diapers.

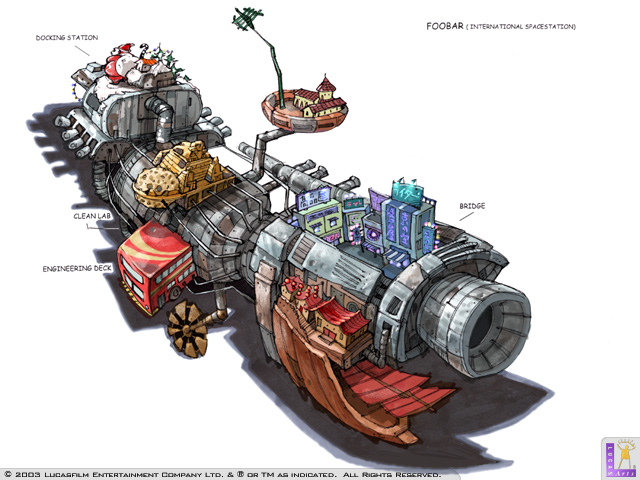

The fifth episode took place on an international space station funded by third world countries, and featured a TRON-like villainous AI protected by a shield of nachos.

And there was a recurring character who played a bassoon. 'Cause I love bassoons and hate animators.

RIGHT: Concept art for the Colfax Pavilion -- the setting of the Winter Festival (in August!) that features in the second episode.

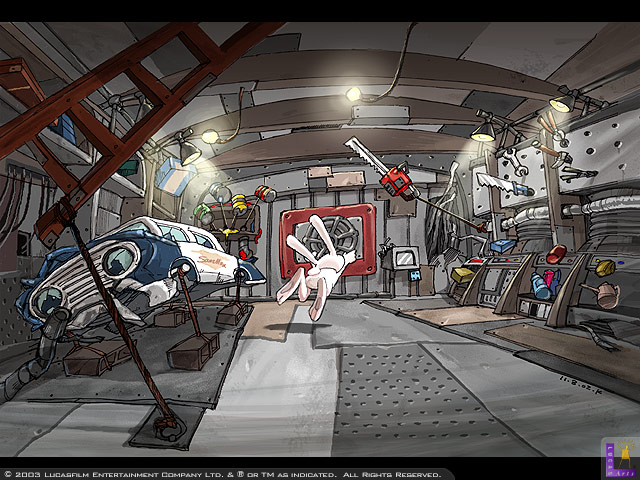

TOP LEFT AND TOP RIGHT: Concept art of “FOOBAR,” the “low rent space station” from the fifth episode. That an episode was set in space may help to explain why Max is seen wielding a ray gun (BOTTOM LEFT) instead of his trademark Luger (BOTTOM RIGHT) in early promotional imagery.

In addition to the inclusion of the Rubber Pants Commandos (a gang of gun-toting babies) from the comics, the game also would have seen the return of Sam and Max’s gumshoe neighbor Flint Paper. A recurring player in the source material, and “appearing” in voice only in Hit the Road, the hardboiled private eye was set to be a supporting character of substance in the sequel. (On the conception of the character, Purcell said: “I always liked that there's a guy in the office next door to Sam and Max who is somehow even more insane than they are.”)

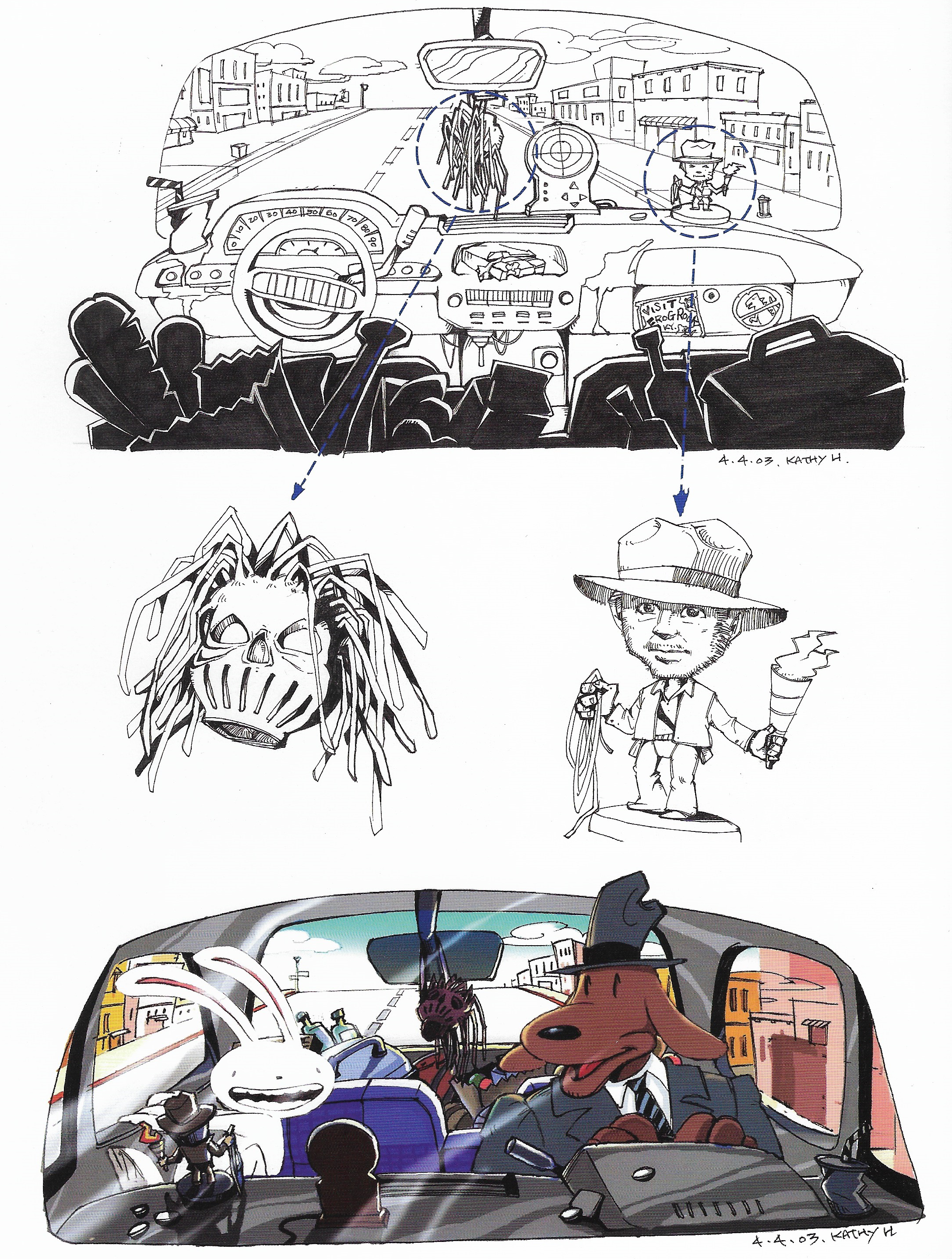

The only glimpse we have of Flint is concept art and a low-res screenshot from a magazine scan. To my lights, the Freelance Police design depicts a rougher-looking Paper akin to that of the comics compared to the round-eyed take Telltale would eventually debut in 2007:

TOP LEFT: Steve Purcell’s concept art of Flint Paper, for Freelance Police, dated January 2003. TOP RIGHT: Telltale’s version of Flint Paper. BOTTOM LEFT: A blurry peek at how Flint looked in-game in Freelance Police. BOTTOM RIGHT: A later piece of concept art of Flint Paper for Freelance Police. This appears to be the one his in-game realization was modeled after.

Structurally and in terms of gameplay, Freelance Police sounds very similar to what Telltale would end up doing with Sam & Max: Season 1 (also six episodes – for whatever reason the magic number), and the team members I talked to seemed to agree with that assessment. From the standpoint of presentation and gameplay, two main differences distinguished what LucasArts was doing and what Telltale would do: mini-games and budget.

Freelance Police would have been utterly jam-packed with mini-games throughout its cases – as many as nineteen, according to one preview. Hit the Road had several mini-games, so it makes sense that they would be seen as a Sam & Max staple, but the sheer volume being planned for the sequel pointed to an agenda. Dan Connors explains: “There was a notion that mini games would make it replayable and more casual. There were neat ideas about virtual awards you could win that could be part of the game.” I find it interesting to imagine how this aspect would have been received by fans had the game ever gotten into their hands. The casting of Real Arcade and its ilk as inspiration in the groping quest to broaden the audience for adventure games seems very much...of its time.

Stemmle remembers that there was some concern about the small scope of the game’s episodic storylines – still novel territory for an adventure game not directed at children – framing the quantity of mini-games as, in part, a fear-based effort to fill out the cases. He now thinks that “we may have been about 39 skoshes too ambitious for our own damn good,” noting that the arcade sequences saddled programmer and fellow Escape from Monkey Island veteran Richard Sun with an unenviable workload.

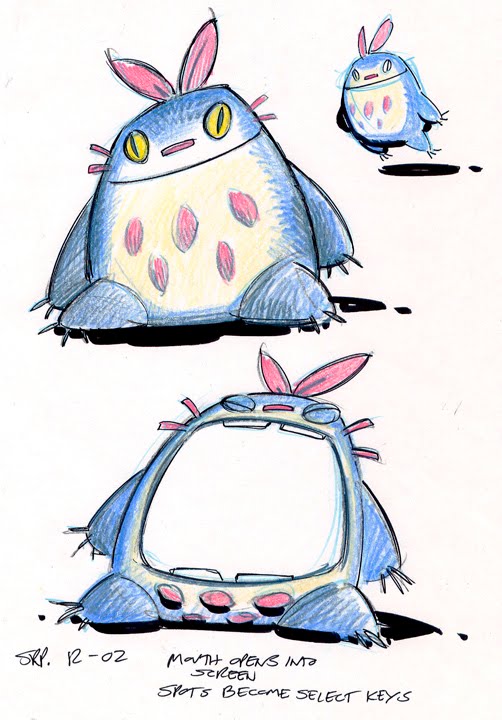

For his part, Sun describes that workload as an enjoyable challenge, though he points out that these segments were mostly in the early stages of implementation, with only a few in a functional prototype state before the plug was pulled. Amusingly, the mini-games would have been collected and replayable via an in-game device called the Gytgo ("Genial Yet Troubling Gaming Organism"), a cross between a Gameboy and a Furby or, as Stemmle put it to PC Gamer, “a techno-organic monstrosity that has nested in Sam's pocket…a hypercute sentient handheld gaming organism that gives the player the ability to replay mini-games encountered by Sam and Max, complete with new levels and power-ups.”

As far as budget, Freelance Police was presumably a modest investment compared to other games being built at LEC, but it was assuredly larger than what’s candidly been described as “shoestring” for Telltale’s initial episodes. This shouldn’t be surprising, as Telltale would have had very little money to throw around in its earliest days, and the LucasArts project furthermore had the benefit of a bedrock of proprietary tools to build upon. Freelance Police was running on a new engine, but one that, as Stemmle indicated in the Adventure Gamers preview, freely borrowed tech from contemporary LEC games. Like GrimE (the Grim Fandango engine that also powered Monkey Island 4), this never-seen engine was based in LUA, but in terms of gameplay, it was SCUMM 3D.

When asked how he would compare the Freelance Police engine with the Telltale Tool, Stemmle ambiguously replies, “I would not.” Steven Chen describes priorities that could just as easily apply to Telltale's subsequent engine: "What I remember most was the animation coordination system, it made it really easy to sequence animations and game events in the game in real-time as we were building it. A very novel idea at the time. Iteration is key in game development and this system made it super easy to try thing out and iterate on them until they were good." Of course, there isn’t a person alive who could better speak to the differences in the respective toolsets than Kevin Bruner, and he says this:

The Telltale Tool was brand new from the ground up. We couldn’t bring any LEC tech with us, and much of the LEC engine was built on top of other LEC tech, such as Render Droid, SMUSH, iMUSE, etc. The LEC game was fancier since it had all that foundation. Freelance Police would have had a lot more variety of game play than the early Telltale games.

That the episodes made with the Telltale Tool were working under heavier constraints is evident enough based on the screenshots we have. Obviously, Freelance Police looks dated – it is an unfinished game built on 2003-2004 tech – and the two games don’t look worlds apart overall, but Freelance Police does seem to have been operating under more advantages in shaders and rendering tools than Telltale could leverage in its infancy two years later. It would arguably take until Telltale’s third and final Sam & Max season in 2010 that they would be able to close the gap and really nail Purcell’s universe in 3D.

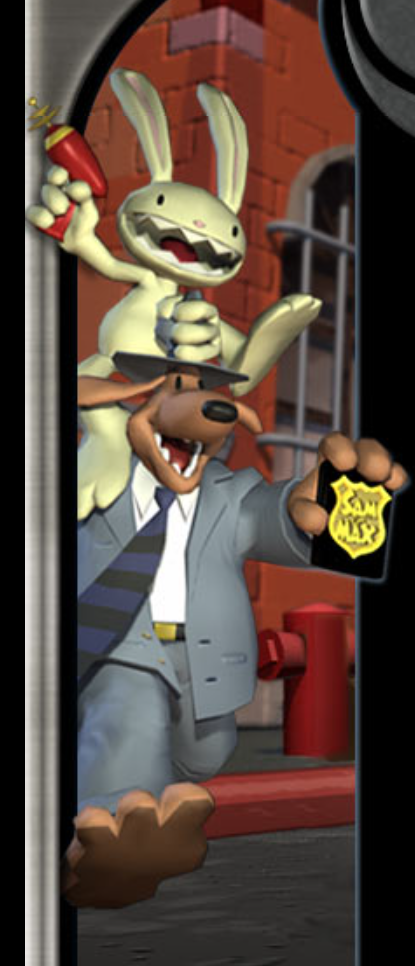

The duo in their office in Freelance Police (LEFT) versus an equivalent screenshot from the first Telltale episode (RIGHT). Though older by two years, the LucasArts version seems ever so slightly fancier, benefitting from moodier lighting effects and more textured character models.

Testimony of the game’s state of competition is inconsistent, with the most extreme rumors at the time indicating that it was as much as ninety percent done. From what I’ve been made to understand, the true figure is somewhere between two-thirds and three-fourths, which still means that Freelance Police was in the home stretch, but it may come as a surprise to fans who assumed the game was down to bug testing that a good six months of full-fledged development remained before it would have reached a shippable state.

Unlike Blizzard’s Warcraft Adventures (unquestionably the most high-profile graphic adventure cancellation before this one), which ended up leaking several years back in the form of a rough but playable-from-start-to-finish build, it seems less clear that Freelance Police was wired together to such an advanced stage. I hasten to point out that I wasn’t able to get any verification on this one way or the other – a failure I detect is owed more to fading memories than to evasiveness.

We do know for a fact that voice work was well underway, with Stemmle estimating that this aspect was about sixty percent completed: “Most of the cut-scenes had been done, but there was a lot in the later episodes that needed to be written/recorded.” The reprisal of Farmer and Jameson was of course the headlining selling point, but Freelance Police would have kept up LucasArts’ high standards from the top to bottom of the cast. Says Stemmle:

I'm not sure if this is widely known, but Penelope Gwinn was played by Emmy-award winning funny lady Alex Borstein. She was a delight. Sgt. Blip was played by Phil Lamarr, another MadTV alum, and a voiceover hero. Also, Mann and Sachs were played by Farmer and Jameson, each doing impersonation of the other. Did I mention that the sessions were fun?

According to Dan Connors, the original idea for that last conceit was to have human opponents Mann and Sacha (described as Sam and Max’s “arch nemeses they never realized they had”) voiced by the actors who portrayed Sam and Max in the animated series (the late Harvey Atkins alongside Robert Tinkler), but were unable to make that happen for budgetary reasons. Bill Farmer himself remembered that sequence as a highlight of the recording sessions when he was interviewed about his experience by the fan site SamAndMax.co.uk:

LucasArts developed a 3D Sam & Max game called Freelance Police. You and Nick reprised your roles and they cancelled the game. I was wondering how far into recording were you?

We recorded for two or three days on that and got quite a bit of stuff done. There was one scene that I remember that I was really hoping would come out where Nick voiced Sam and I voiced Max. Like our brains got switched. That was a fun scene. Incidentally, they never really told me they’d cancelled the game. I didn’t find out until like a year later.

Wow, really?

It was like a month or two between times we went in. We do a large block of this stuff and then we come back because there are thousands of lines in these games, so it takes days and days to do this. We did two or three days and then nothing happened and I’d ask my agent, “Hey, what about the Sam thing, is that coming up any time soon” … ”Well, we haven’t heard” … and we never heard! It was actually through fans online that I found out, “Oh, it was cancelled.”

That’s bizarre!

I was the last to know!

The game’s soundtrack was the duty not of Hit the Road’s celebrated trio (Peter McConnell, Michael Land and Clint Bajakian) nor of the franchise’s future musical custodian Jared Emerson-Johnson, but of Mark Griskey, an internal LEC composer whose credits in those days included Gladius and a whole bunch of Star Wars; his work would be abetted by sound designer Nick Peck. It is a safe bet that iMUSE would have been used to its usual, incomparable effect.

While we sadly have no access to Griskey’s work except, presumably, what you can hear in the E3 2003 trailer and in the Joe White clips (which certainly suggest his compositions were of the jazzy character we associate with Sam & Max), he tells us that the game was going to lean heavily into the noirish influences of the characters, and that he had gotten as far along as scratch tracks. When the plug got pulled, he was negotiating to get as many live instruments as possible into the eventual recordings. These efforts were up against reluctance from the studio to invest in audio production values of the highest grade: “I had a hard time getting anyone to commit to a decent music budget,” he remembers, “and was scrambling to find musicians to work for a modest fee for the mockup tracks and was hoping that we would get approval to go into the studio for more polished final tracks.” While Mark believes he may have the scratch tracks somewhere in his archives, legal restraints prevent him from sharing them.

Although our view of Freelance Police’s development is far from intimate or privileged, there’s been a decent driftnet of information collected over time. Nothing that those intervening fifteen years have brought to light would conflict with Stemmle’s repeatedly laudatory characterization of the project’s crew as a dream team.

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo