Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

Like a lot of ills in this world, the blame for what happened to Sam & Max 2 can be laid at the feet of the Star Wars prequels.

I’m only sort of kidding. If you want to understand the terse press release of March 3rd, 2004, you have to get a sense of the LucasArts that existed five years before Freelance Police was even announced, for that’s when a number of critical seeds were planted. The late 90s were a major turning point for LucasArts down to its very identity, and not entirely for the better.

At first blush, it can be hard to say anything too negative about this era. The studio was still putting out some exemplary games, perhaps even its greatest among them. I’m not moved to argue with anyone who would assert that The Curse of Monkey Island (1997) or Grim Fandango (1998) were the best things to ever come out of LucasArts, full-stop. And though the context of the late 90s being a time when the internet became a more accessible luxury must be factored in, one cannot dismiss the fact that this was also the very period where the online fan scene – Mixnmojo included – came into being, as that sort of concentrated obsession isn’t likely to be spawned by a creative enterprise that has completely lost its way. Nevertheless, in concurrence with LucasArts’ continued achievements was a clear trend toward the black hole of Star Wars.

As has become established lore by this point, Lucasfilm Games (the studio’s moniker before a major restructuring in 1990 – and again today, as it seems to have reverted under Disney to its original branding) at first did not touch the Lucasfilm movie properties, and the valuable built-in awareness they came with, as a matter of policy. The idea was to instead license those out to other companies, thereby assuming no overhead and just collecting a check. Since these licensing deals had been hammered out in the early 80s, the original team at Lucasfilm Games couldn’t have made their own Star Wars games during those initial years even if they wanted to.

Internally, the “Games Group,” as the skunkworks division was referred within its uncommonly independent halls of the Lucasfilm empire, invested almost entirely in new properties like Rescue on Fractalus! (1984), Ballblazer (1984), The Eidolon (1985) and Koronis Rift (1985) while it let the likes of Atari develop the earliest Star Wars games. With some ad hoc exceptions to accompany the film releases Labyrinth and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, this policy remained in effect even once the studio made the jump to self-publishing with the seminal Maniac Mansion (1987), which debuted the SCUMM engine. As a work environment, Lucasfilm Games looks from the present-day perspective downright implausible – a vibrant combination of tirelessness and puckishness sustained by the patience of its endowed namesake. It was not, by any stretch, a normal game studio. And while a shift was inevitable, it wasn’t an upgrade. The only thing worse than leaving the inmates to run the asylum, it seems, is leaving it to the professionals.

However untenable that early culture may have been, the aggregate result speaks for itself. The first ten years of the studio’s history produced a catalog that is still legendary for its creative highs. It’s hard to imagine a game as captivatingly strange as Loom (1990), for example, being birthed anywhere else (and certainly not with comparable production values), and envelope-pushing experiments like Habitat (1985) – the first MMORPG – contribute to a picture of Lucasfilm Games as an almost Wonka-like R&D laboratory for interactive entertainment. (And that’s to say nothing of the other divisions, The Graphics Group and Droid Works, which respectively generated minor contributions like Pixar and the world’s first non-linear editing software.) Any reader of this site hardly needs the titles which illustrate the studio’s heyday as something special to be listed out; it will suffice to say that the fourteen graphic adventure games produced under its logo remain the genre’s pantheon and the molten center of everything LucasArts stood for when it built its original fan base.

By the early 90s, the studio relaxed the policy that encouraged this invention and began to indulge in making its own Star Wars games, and from that point forward there may have been no turning back. At first, the Star Wars titles and original titles seemed to coexist in equitable harmony, and in general anyway (the outsourced and unimpressive NES game was a weird choice for recent canonization), those of the former category upheld the studio’s high standard of quality; this was the era of X-Wing and TIE Fighter. A handful of excellent Star Wars games was hardly grounds for complaint, especially when they were being released alongside the likes of Day of the Tentacle (1993) and Sam & Max Hit the Road (1993).

This vintage promotional video, showing off the company’s line-up of 1994, plays like the greatest hits of an era.

But with the vantage of seeing the thirty-year story as a whole, it is evident that some switches can be thrown in but one direction. As seems to happen as a matter of course once a company gets its beak wet on gigantic licenses, the die was now cast, and it was only a question of time before LucasArts became indivisible from the undeniable cash cow they began with a disciplined approach toward.

It’s easy to judge all that milking, and warranted as well. Still, when put into perspective, the overwhelming power of a recognizable brand in the marketplace is downright sobering. The lay of the land is made quite clear when Noah Falstein refers to a conversation he had with the head of Lucas Licensing that “put us in our place.” When the designer mentioned to his colleague how he was encouraged by the growth the video game division seemed to be enjoying, with PGM Pegasus (1986) “breaking records,” he was met with a chuckle and an explanation that Lucasfilm made more money on a single deal to license Star Wars characters for a line of pajamas than the Games Group brought in over a year.

In the clarity of that contrast, an argument presents itself: The initial unavailability of Star Wars to the game developers was a gift from heaven masquerading as a limitation. In terms of preserving creative liveliness, it bought the studio time, forestalling the inevitable. The surpassing eminence that was earned in the 80s (and coasted on later) was not merely an artifact of this grace period, but the result of it. No more than you can unlearn the alphabet, the green eyeshades in Sales were never going to un-see the numbers that Star Wars games – the good as well as subpar – would generate once the padlock was removed, especially in contrast to even their profitable original titles. The rising costs of PC development in an increasingly console-driven marketplace, another current that seemed to flow but one way, could only have promoted this risk-adverse bent.

It’s no unique story. More studied pupils of the history of the games industry can doubtless conjure a number of other examples of a studio’s trajectory after it nabbed its first high profile license which will underline the same pattern. We don’t even have to look past the Mixnmojo sphere to cite other analogues. Ron Gilbert attested to this very phenomenon when he conveyed that Humongous Entertainment was never the same after it put out its first Blue’s Clues title. Despite the modest but reliable successes of Putt-Putt, Freddie Fish and Pajama Sam, the company’s original flagship series, there was simply no comparison in the numbers, and Humongous’s story after that, including the acrimonious dispersion of its founders, is so predictable as to be predefined.

To cite a more recent example, Telltale Games, whatever noises it may have made to the contrary, was never really going to find room again for the types of licenses it cut its teeth on after The Walking Dead redefined expectations. Perhaps the LucasArts arc hurt more for the witness because of the unparalleled creative heights it fell from, as though the studio was somehow too special to fall victim to such routine trappings.

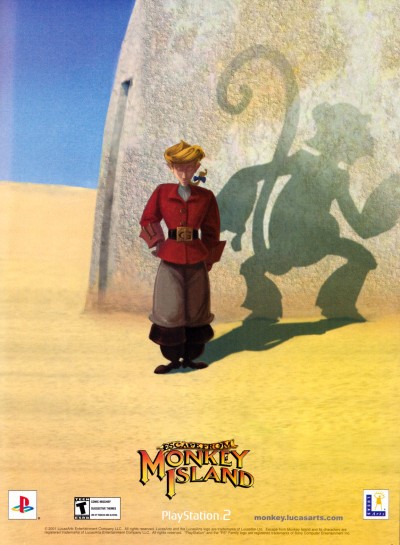

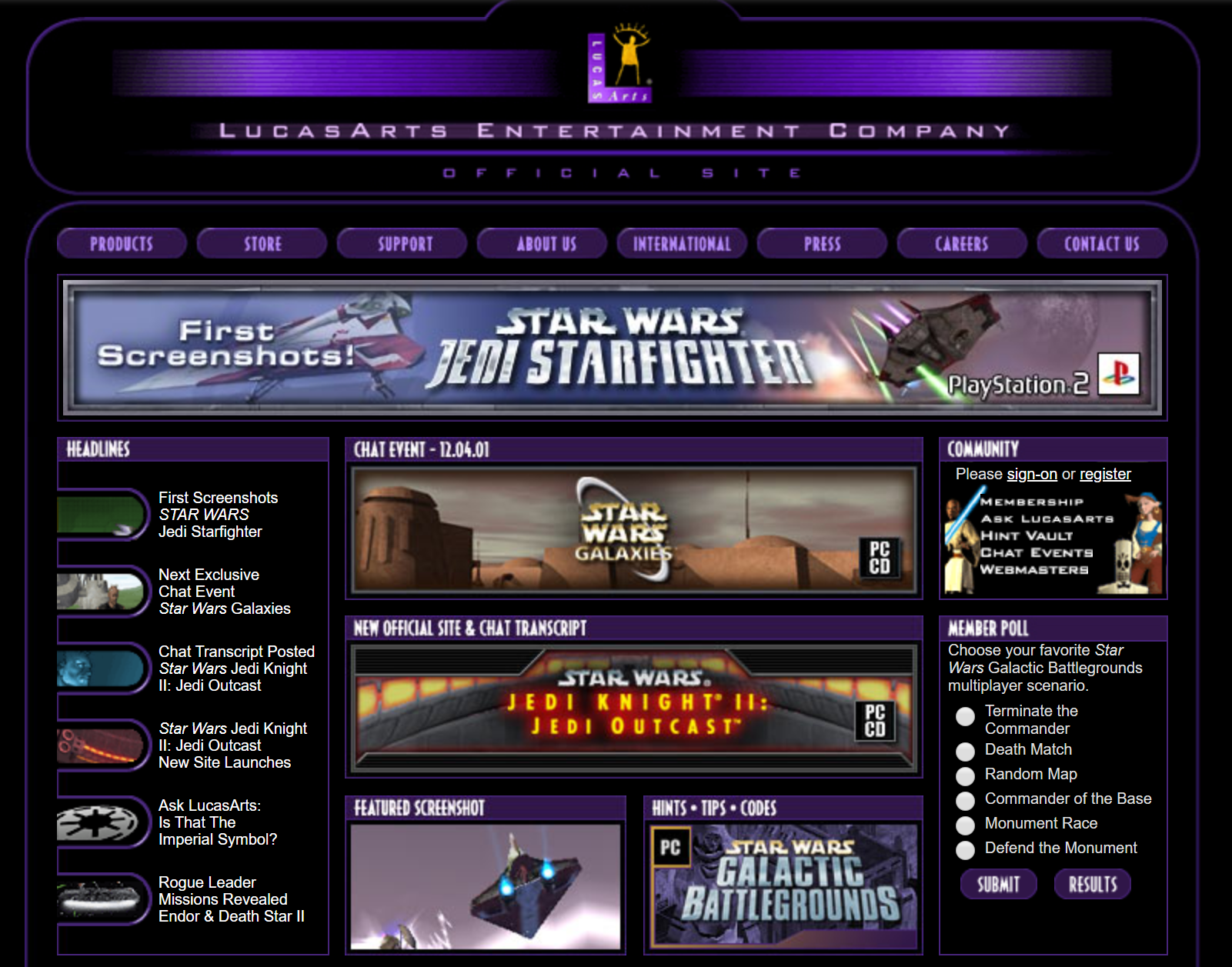

Throughout the 90s, original titles slowly but surely became less frequent at LucasArts (even if, as mentioned, the few adventure games they still deigned to greenlight were home runs), while the company willfully shifted to an identity more or less synonymous with “Star Wars Interactive.” That may have been an obvious destiny from a business perspective, but it represented a fairly drastic departure to anyone who fell in love with the studio for its output during the Skywalker Ranch days. It is difficult to find a nexus between the studio that made Guybrush Threepwood or Bobbin Threadbare and the studio that practically tripped over itself to churn out a Darth Maul kart racer.

If this journey to becoming the video game arm of the Star Wars franchise was an inevitable one for LucasArts, there was certainly a context that allocated it about fifty extra horsepowers: the Star Wars prequel trilogy. George Lucas’s long-anticipated films, the first cinematic content from the monster franchise since 1983’s Return of the Jedi, were at last heading for production, and of course the interactive division of his empire was going to exploit the opportunities it proffered.

And exploit they did, with a vengeance. Even the most die-hard of Star Wars fans would admit that the sheer volume of tie-in games cranked out during this period was: a bit much. But LucasArts President Jack Sorenson, or perhaps the board he answered to (for it’s always been rather ambiguous how much autonomy any LucasArts president, a position which technically didn’t exist until 1993, ever really had), enacted a charter that in the clearest possible terms would triple-down on Star Wars at the expense of anything else.

LucasArts had completed a 180-degree maneuver: They began by shirking Star Wars entirely, evolved toward a fairly balanced approach toward it, and finally embraced it unconditionally, making it all but the company’s identity. “There was definitely a sense that the company was shifting towards a ‘Mostly Star Wars with Just Enough Original Material To Maintain Our Rep’ footing during those years,” agrees Mike Stemmle, the writer/designer who served as Project Lead on Sam & Max 2.

There were consequences to this, and though they may not have been immediate, they became symptomatic in time to make trouble for a certain dog and rabbity-thing when they attempted to stage their long overdue comeback on the computer screens of neglected fans.

But that was still a few years down the road.

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo