Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

“Despite LucasArts’ secretive ways, total lack of information, and general shut-uppery about Freelance Police, I’m still looking forward to it more than anything else they had at the show.”

So wrote Jake in Mixnmojo’s original preview of Freelance Police from E3 2003, annoyed by what seemed to be a gratuitous media and informational blackout, especially by comparison to the blitz that comes with most announced games at trade shows -- and this game had been announced nine months earlier.

Improvement on this front was slow. On the inside, the production of Freelance Police may have been a creative frenzy, the shrouded fruits of which would have sent the fan base into fits of joy, but on the outside there remained frustratingly little tangible information and pretty much zilch in the audio/visual department. The significant exception, of course, was the aforementioned E3 2003 trailer:

The reaction was uniformly positive despite how little it actually illuminated. The purpose of the video seemed largely to unveil Sam and Max’s transition to 3D. (Even this had some asterisks, as neither of the characters’ 3D models were yet final. The media that surfaced later showed off more refinement, complete with bump-mapped skin for Sam and the correction of Max’s triangular teeth.) And with no genuine gameplay footage or even screenshots in sight, LucasArts was still opting to play things irksomely close to the vest.

Still, what we did get made a positive impression, and the trailer certainly kicked up less concern than Full Throttle 2’s released media. The animation was fantastic, the voices spot-on, and the spirit and humor of Purcell’s creation most definitely intact. As the most circulated artifact of the game’s truncated publicity campaign, it served to generate a good deal of excitement and convince all but the most hardheaded reactionary that this was going to be a return to form worthy of a day one purchase.

At the time, one might have thought the trailer signaled that the dam had at last burst and that marketing proper for the game had now commenced. In fact, the torture continued, and relief wouldn’t arrive until 2003 wound down. The truth is no doubt that the game was simply not far enough along yet to make a screenshot deluge possible in the Spring of 2003, but for fans it felt somehow like a deliberate shunning. In the context of what else was going on at LucasArts, the infrequent news we would get on Freelance Police was both tonic and torment, and its relative absence may have helped sap some goodwill for the more prominently displayed original games from an audience feeling neglected.

In that light, it’s understandable that the cancellation of Full Throttle 2 in August fomented some worry among jittery members of the community. Was Sam & Max 2 going to be next? For the most part, the fans reassured themselves that the two projects were in completely different situations, and that was nothing but true. Fears of the worst were further diminished with the inclusion of Hit the Road and the Freelance Police trailer on that Armed & Dangerous pre-order disc – an offer from online game retailers which became public in October and seemed to indicate that the hype machine was at last revving up – then inflamed again when Simon Jeffery stepped down.

Though it would not come from official channels, November brought an exciting development in the form of an account of one of the Freelance Police recording sessions. The source was a member of the impressively still-active Something Awful forums named Justin who claimed to have been able to attend a day-long session due to his friendship with an engineer at “Margarita Mix” in Hollywood, where the recordings were taking place. The original Something Awful forum thread no longer appears to exist, but a copy of the text can be found here, in the Adventure Gamers forum archive.

(Unfortunately, this copy does not preserve the media that originally appeared throughout the write-up that put the author’s veracity beyond doubt. This included photographs as well as a voice mail greeting that the author got Bill Farmer to record for his cell phone. The latter at least got circulated enough at the time that the file survives; listen to it here.)

The account offers a number of enjoyable anecdotes, vague tidbits about settings, mini-game descriptions, sample jokes, and a reference to a 400-page script (representing only one third of the projected dialog) that the all-day session was picking up in the middle of. The most exciting part was the author’s claim that Stemmle had played him a promo that was meant to be released in the near future and featured an appearance from the project leader himself. This fun bit of marketing nonsense, which probably would have found itself under that “Trailers” section of the web site, wormed its way online decades later and can be watched below:

What’s included in this article represents every shred of Freelance Police media known to exist on the web, though Stemmle has recently said “I have all the cutscenes on DVDs here at home.” Alas, it would probably take Mickey Mouse himself pre-emptively indemnifying folks from legal repercussions to get any surviving assets related to the title out in the open. It will surprise no one that my attempt to get in touch with Lucasfilm/Disney for this article, much less negotiate blanket immunity on behalf of anyone who hypothetically has material to share, found no purchase.

In December, LucasArts.com launched an online survey that sent fans into a fit of speculation. Sam & Max and adventure games in general were primary topics, and opinions were canvassed for on such provocative matters as the appeal of mini-games and the palatability digital distribution. Again, this was before the major significance of either to the title was well known on the outside.

In the moment, the Mixnmojo reaction to the questionnaire was bemusement and even excitement, but in retrospect it seems that the implications ought to have been ominous. The most extreme interpretation is that LucasArts had recruited a marketing firm to gather “data” that would confirm whatever biases they had about the project’s viability. Or maybe it was an innocuous bit of information-gathering after all. “It does sound familiar,” says Stemmle when I bring up the survey today. “I think it was something Dan put together. The timing of it may have just been... unfortunate.”

It wouldn’t be until the new year that things finally began to get more tangible. The fact that Spring 2004 remained the projected release window despite the relative quiet up to that point sent a pretty clear signal that a delay was in the offing (note the “Summerish” release advertised at the end of the above video), but this implication – hardly uncommon with games – seemed subordinate to the arrival of hard information at long last. First on the scene was an interview with Stemmle by CVG in January. Due to its age and brevity, I’ll reprint the text in its entirety:

They're back. Tumbling out of the mystery vortex and on to our hard drives, Sam and Max, perennial slapstick/wisecrack heroes and investigators of obscure Americana, are about to jam their wet noses straight back into our lives.

We cornered Michael Stemmle, director of all Sam & Max-related activities at LucasArts, offered him a box of Snuckies Pecan Candy and a sample of Sasquatch hair and he had all this to say...

How would you describe Sam & Max: Freelance Police to someone who hasn't heard of the dog and rabbit crime-fighting duo before?

Sam is a dog. He wears a suit, and has been known to play the banjo... Badly. Max is a naked, hyperkinetic rabbity thing. Together, they upset the apple cart of crime as the Freelance Police, a vaguely sanctioned, rarely discussed branch of the criminal justice system.

Are you confident that this move into 3D will be more successful than the recently cancelled Full Throttle sequel?

I don't know if 3D has much to do with the success or failure of any game. But I do know that Sam and Max look great in 3D.

How will the control system work now that the game is in 3D? Compared to how it played in the original point 'n' click adventure?

Pretty darned well. All we've done is taken the old 2D point 'n' click system, and replaced the '2' with a '3'. OK, I hear there was also some programming involved, but that's the essence of it.

Will there be mini-games as in the first game?

Will there be mini-games? Will there be mini-games? There'll be more mini-games than you can shake a genetically altered lab rat at, you young whippersnapper! And that's a good thing, because one of our dozen or so mini-games actually revolves around the shaking of genetically altered lab rats. In space. In 3D.

Can you tell us anything about the story for Sam & Max: Freelance Police?

The story of Sam & Max: Freelance Police is really six stories, loosely held together by a thrilling über-plot. The individual stories are wide-ranging cases of the Freelance Police, featuring exotic locales (such as a low-rent space station, and a lame-ass neopagan desert bacchanal) and freakish bad guys (like an exceptionally honked-off Miss Congeniality, and a rogue artificial intelligence made out of tortilla chips).

We're trying to keep the über-plot under wraps for now, but suffice to say it features all the barely plausible grandeur that fans have come to expect from Sam and Max.

Will any characters from the first game make a reappearance?

Besides Sam and Max, the only other character who's officially returning is Flint Paper, the Freelance Police's rough 'n' tumble private detective neighbour. He actually plays a critical role in the über-plot.

What's your favourite bit in the game so far?

Our Jump, Jive, and Flail mini-game. I never suspected that Max would be so light on his feet.

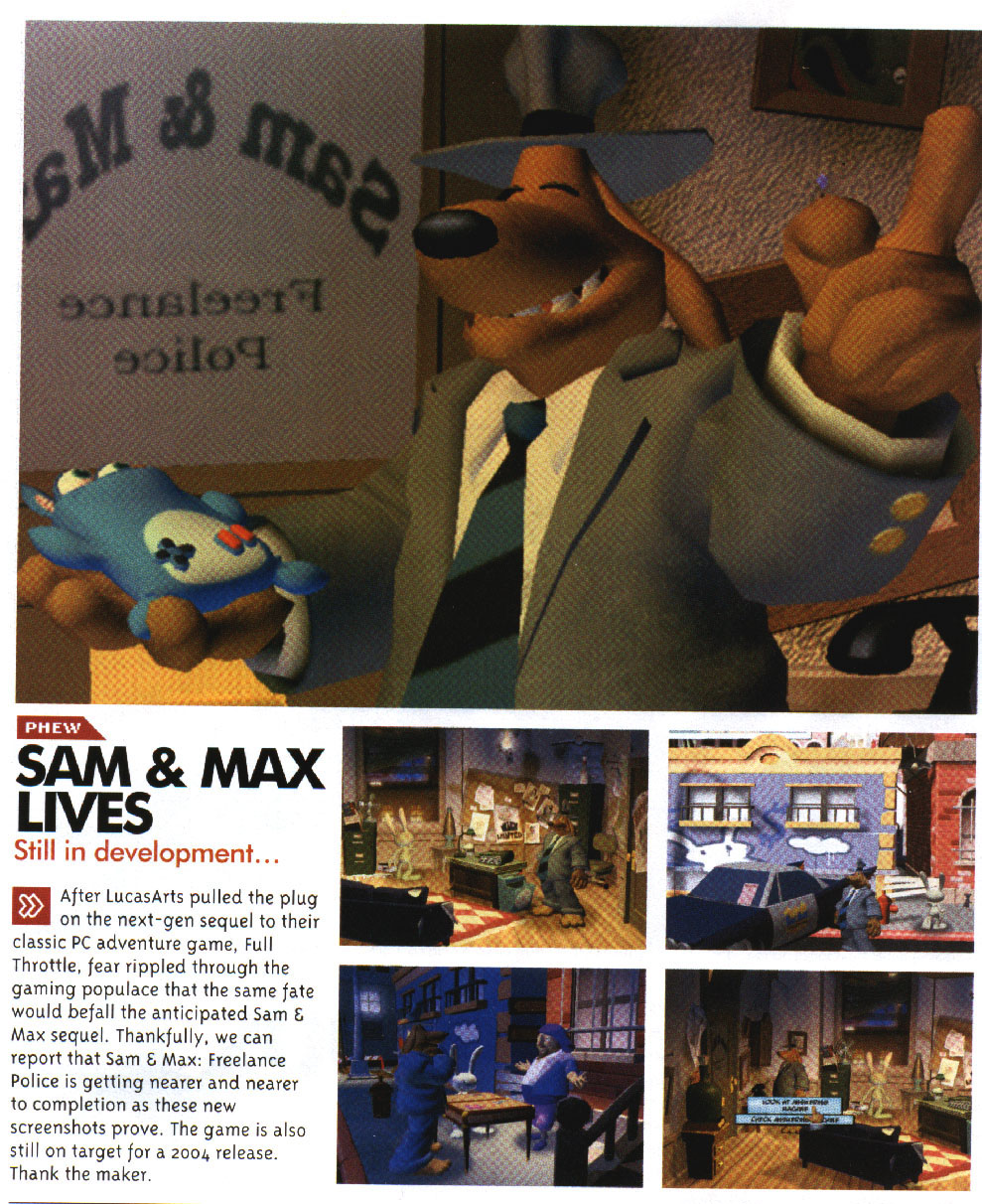

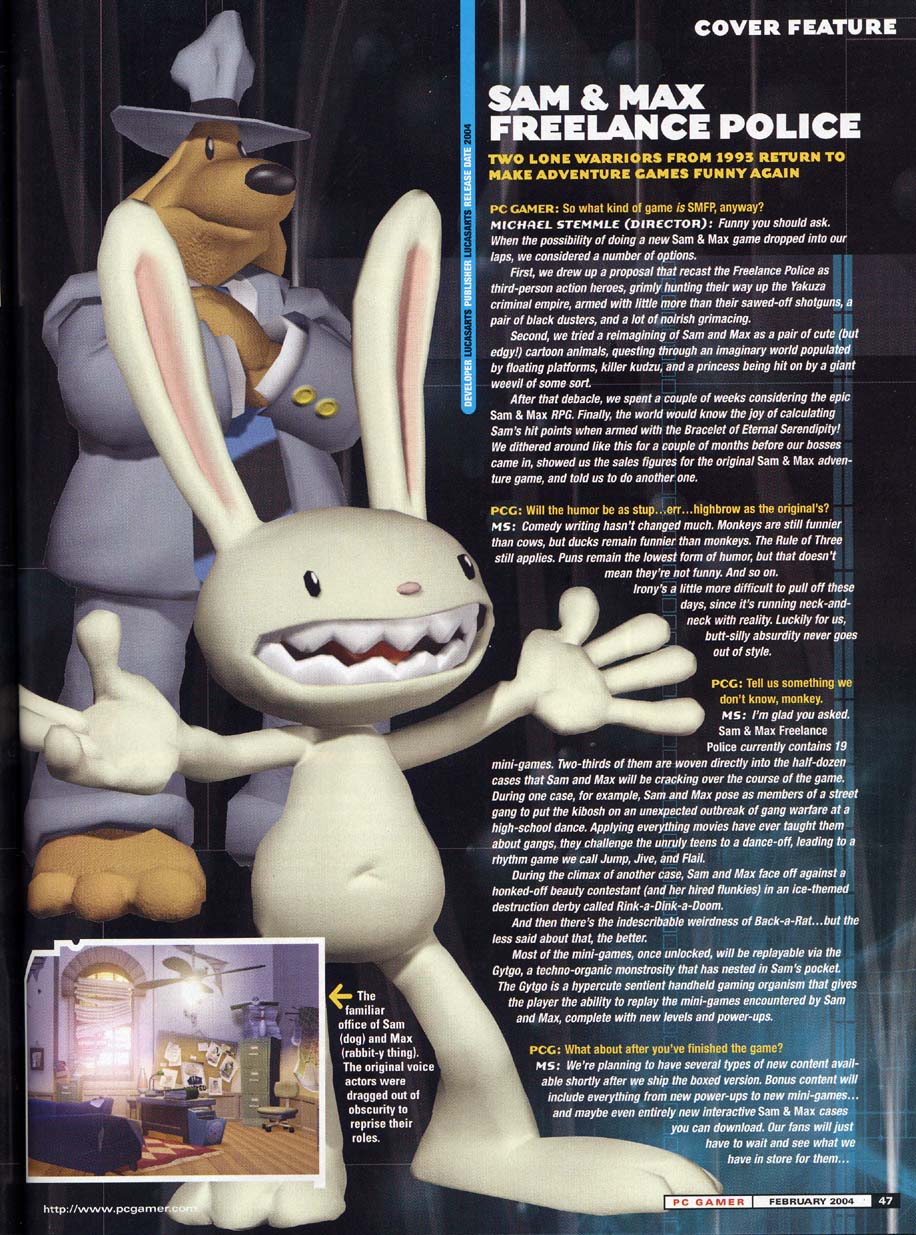

The next week came with a preview by PC Gamer, the print version of which appeared as a cover feature in its February 2004 issue. In other words, the first proper magazine preview was published mere weeks before the game’s cancellation (and amidst the commercial failure of Wrath Unleashed). A scan of the preview can be found on the left.

Only a few days later, the newly relaunched Sam & Max.net (which was part of the same network as Mixnmojo and was run by some of the same folks – specifically Jake and Metallus) was thrown a bone courtesy of Ronda Scott in the form of a gorgeous, high resolution (2550 x 1650) version of the environment render of Sam and Max’s office (it also appears in tiny form in the PC Gamer preview) as it [would have] appeared in Freelance Police.

The beginning of February saw the emergence of another magazine preview, this one from the Australian magazine Hyper. It contained the very first in-game screenshots of Freelance Police, and despite the blurry quality via the scan that soon circulated, it sent fans into a blissful tizzy down to the most trivial details, including the reprisal of Sam’s paw as the mouse cursor – a testament to how starved we were.

The screenshots also spawned a little bit of good-natured controversy. Although earlier quotes from LucasArts pointed to the game employing a real-time 3D point ‘n click engine (the first of its kind from the studio), this was never unambiguously declared, and the less-than-ideal quality of the magazine scan kept the matter unresolved, leading some to air the suspicion that Freelance Police would after all feature pre-rendered 3D environments, not unlike Grim Fandango or Escape from Monkey Island.

No less than Mike Stemmle stepped in to helpfully clear the matter up. On February 10th – again, weeks before the plug was pulled – Sam & Max.net published the following write-in from the game’s project leader:

Actually, it’s full motion video with a toon shader; you just can't tell from those scanned screenshots you’ve been seeing. What’s missing from those shots is the surround smell technology and the motion-captured animation of a naked midget in a rabbit costume.

Kidding.

For the record, Sam & Max Freelance Police uses an honest-to-George real-time 3D renderer. Its “so-pretty-it-must-be-pre-rendered” look is achieved via a precarious balance of shaders, bump maps, lightmaps, and a little thing we like to call “sweet, sweet lovin’.”

It was all terribly exciting. It was also the last bit of information that would come out before the game got cancelled on March 3rd.

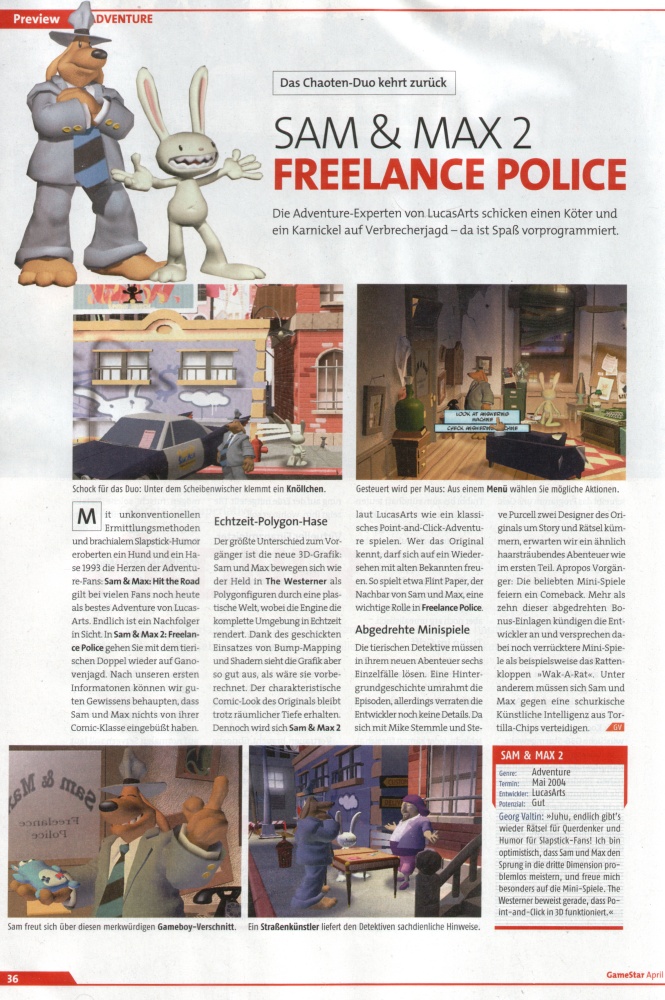

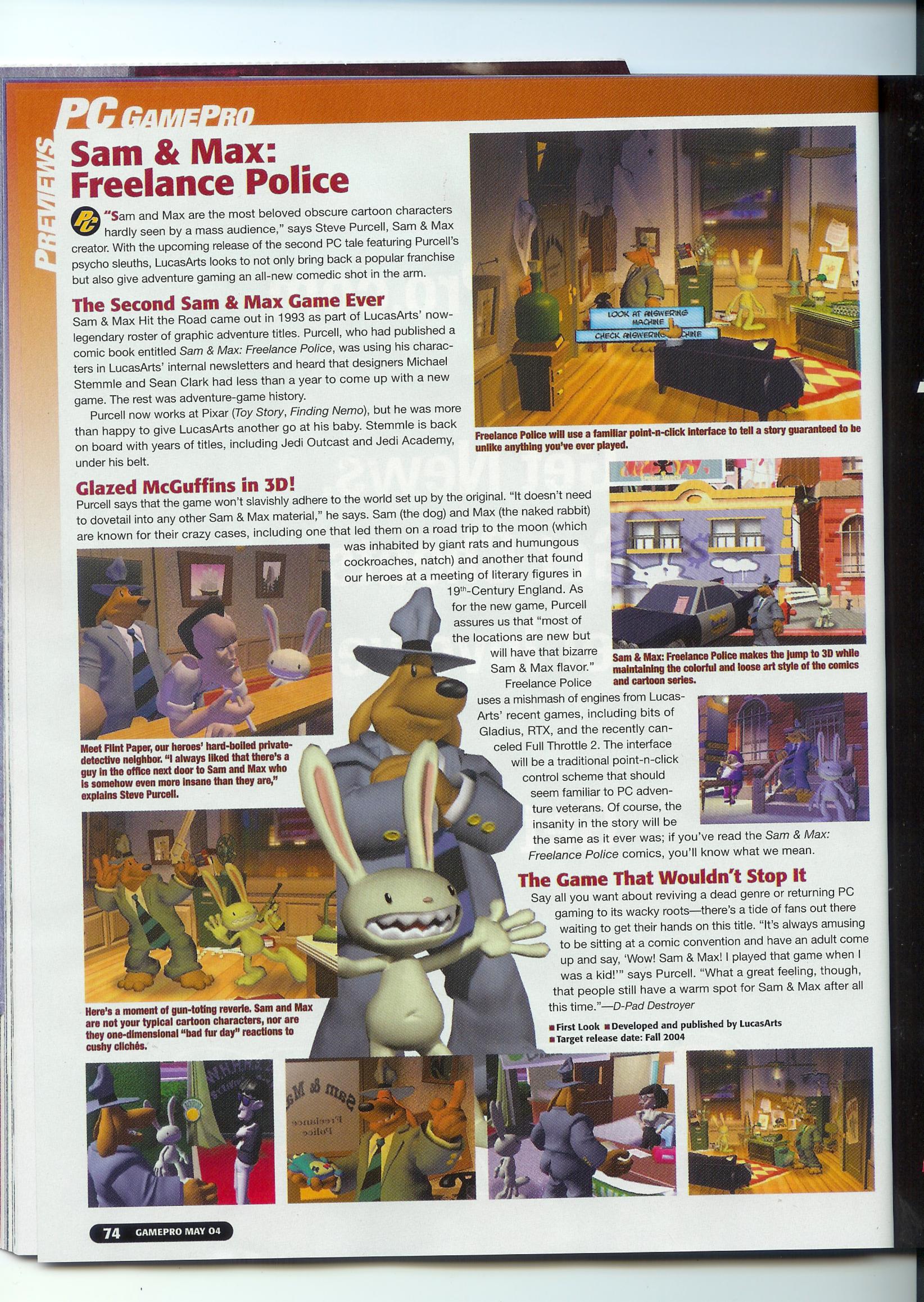

Ironically, magazine previews would continue to emerge in April and even May, breathlessly promoting the game as though it was still on the way. This is of course an artifact of the delays between writing and publishing that are intrinsic to print media running on a monthly schedule, but even accounting for that it betrays how abrupt the decision must have been. (The high-quality screenshots that appeared around this time were sourced from the online presence of the German magazine Gamestar, and are therefore, and despite the awkward timing, official releases shared by LucasArts to the press for publicity purposes.) We’ll explore that surrealism a bit more on the next page, which will cover the fan reaction.

Below are scans of the final three magazine previews. The May preview, you’ll note, adjusts the release window from Spring to Fall 2004.

RIGHT: From the May 2004 issue of GamePro.

The suddenness of the cancellation begs the question of how smoothly development could really have been going. There seemed to be no common denominator between the portrayal of the game’s progress by the team (both at the time and in retrospect) and the decision to shut it all down. Only the tiniest pushback against the utopian picture of the game’s production came out of the new interviews I conducted for this article, and I point out that the team members were by and large frank and unskittish when sharing their memories.

Dan Connors opines that willful compartmentalization may have played a role in shielding the team from whatever hostility toward the project might have been brewing upstairs, but this is no smoking gun, and would only seem to reinforce the unanimous perception that the project’s difficulties were external rather than internal. That the game had fallen behind by several months, which had been acknowledged within the studio and was long self-evident from the outside, is really the only thing one can grab onto. “Candidly, Freelance Police was starting to run over budget and slip its schedule,” affirms Stemmle. “Nothing catastrophic, but it was going to require some serious closing work to get it out the door.” It remains an exceedingly unsatisfactory explanation for terminating the project.

The question that was stammered by heartbroken fans at the time therefore seems every ounce as valid today: Why would it make business sense for LEC to scrap a game in which so many resources were already invested, and in the absence of acute quality problems such as those Full Throttle 2 suffered? Even if the rudderless (recall that there was no president at the time, though the incipient one might have already been weighing in) brain trust had convinced themselves that the game couldn’t turn a profit, the investment thus far was spent money; wouldn’t losses at least be mitigated by getting the thing released to do whatever business it was going to?

Perhaps the mistake is assuming that there must be an obvious, logical answer to this at all, though Kevin Bruner makes the point that in terms of the company’s finances, there was a wider picture beyond whether or not Sam & Max 2 in and of itself was a profitable proposition: “Remember, it’s not just about this one game, but also about the best use of the studio as a whole, and adventure games stopped making sense for them at that time.” The message, then, is that the game wasn’t so much seen as a bomb in the making but simply too small potatoes to bother with when there was real money to be made elsewhere. Some of LucasArts’ best talent was working on Sam & Max 2, and the management wanted all operating pieces on the board allocated to Star Wars projects now and not tomorrow.

That the developers were caught unaware is hardly a failing on their part. If we’re supposed to believe that the team was engaged in some kind of group denial about whatever internal atmosphere was putting Freelance Police in the crosshairs, then the fan base was certainly no less guilty of dismissing unfavorable winds. Re-reading the reactions to the various mishaps of 2003 that have been covered, Mixnmojo’s overall attitude might be described as recklessly blasé rather than overly concerned.

As much as the string of flops, or the cancellation of Full Throttle 2, or the fateful departure of champion Simon Jeffery, raised hackles on an individual basis, faith in common sense precluded any prediction that this could all culminate in some panic-driven, knee-jerk decision wholly independent of problems with development itself. Jonathan Sgro’s perspective could have been a copy/paste of the mindset fans were expressing in their commentary: “I think we were wary after FT2 was canned, but SM2 was a better product and so close to completion. It seemed silly to cancel it.”

The remainder of the high-quality screenshots that LucasArts provided to GameStar magazine. The top-left screenshot is our only peek at the game’s point ‘n click interface.

I tried to get a sense from the developers of what the last days of the project were like, and if there was anything in hindsight that should have made what came less surprising. Stemmle insists that, as the fans have always believed, the cancellation was “Totally sudden. No foreshadowing. Not even any twoshadowing.” That doesn’t mean his bosses weren’t ready with peer-reviewed “studies” to justify it as a business decision. Speaking now, Stemmle refers to a surreal meeting that he has brought up a few times in the past:

All I know is that I was brought into a small meeting room, and told in no uncertain terms that the entire European adventure game market had literally disappeared. There were 100,000 of them one year, and the next, nada. To this day, I wonder if the game was cancelled due to a rounding error, or some sort of half-assed European preview of the Rapture.

It’s unclear whether or not he’s being facetious here, but I’m inclined to believe that it’s not far from the truth, because a separate meeting that Dan Connors remembers isn’t appreciably less farcical. Freelance Police’s producer recalls that at the end of one work day “they invited me to a meeting at Lucasfilm with LucasArts publishing and some LucasFilm folks where a Kellogg Business School grad student explained how downloadable games wouldn’t be viable for 10 years.” Yikes.

However partisan or nonpartisan we might imagine these geniuses were being with their arithmetic, the bottom line is that LucasArts suddenly convinced themselves, quite late in the game, and pointedly after all those non-Star Wars misfires, that the numbers just weren’t gonna crunch for Sam & Max 2, gosh darn it. Speaking on camera to GamePro during his time at Telltale, Stemmle was admirably philosophical when describing the perceived viability of adventure games at that time, but you sense this diplomacy is a tad forced when he concludes, “I don’t know too much about the number stuff.”

As for how the word actually came down to the development pit, it all sounds fairly prosaic, which didn’t stop it from being traumatic enough that it was partially blocked out by those most affected. “They probably told me and me and Mike told the team. It likely sucked immensely,” says Connors as though he was a third party. Bruner had this to say about how the team was informed, and to my question about whether any lobbying against the decision occurred:

I think we were told by Steve Dauterman* (if I recall correctly). We were all obviously disappointed but it was clear the decision had been made. I think the team was experienced enough to understand that “lobbying” for anything wouldn’t do any good. There wasn’t a lot of malice, just disappointment.

Derek Sakai remembers it like this:

I came into work one morning and it was pretty much "This is what's happening". I had no idea leading up to that point that there was even any discussion of the project being potentially cancelled.

[…]

I just remember being very disappointed since we were so close to being done and couldn't really understand at the time why such a drastic decision was being made so suddenly.

Graham Annable:

It was one meeting. They called us all in to a conference room and told us they were pulling the plug on the project. It was presented as not a reflection of our effort but more a reality of where the games market was at. I think the managers who delivered the news were legitimately sincere about how sorry they were but it still felt like a horrible gut punch at the time. It hurt to not have them support us all the way through to the end, regardless of what the market appeal was deemed to be.

Steven Chen:

When the project was cancelled Mike pulled the team into a conference room and just said that we were stopping development and that management felt that the fans of the genre while passionate about it were not growing in number and that it wouldn’t be financially viable to release it. Cancelling a game well into development is a hard thing to do. People put their heart and soul into a it and there’s no way to not have it be a huge downer for everyone.

Purcell, being a level removed from the production office, received the bad news from Stemmle. As recounted in Telltale’s “Summer of Sam & Max” web feature in 2007:

Steve remembers getting a cryptic email from Mike asking him to stop by the office. "Of course that was right at the moment when things had seemed to be cruising along without a hitch. That's how that kind of thing always seems to go." So how did Steve feel about the cancellation? "I've worked on projects that have gotten cancelled before so I think I took it pretty well. I felt worse for the crew, who had a lot more of their time invested than me. I knew that the public might automatically assume the game had been in trouble so I issued an official comment to let fans know the game itself was in good shape--that the decision was strictly a marketing choice."

The creator of Sam & Max also remembered that the team "gallantly continued working on the game like the musicians on the Titanic," which is exactly what the developers at Double Fine did one month later when Psychonauts got dropped by its first publisher, to a much happier outcome. The way Richard Sun remembers it, Freelance Police carried on for a few cruel months after its death sentence (“because when the brass took a look they kind of said, ‘oh crap, this is actually pretty damn cool…maybe we should rethink.’ And then decided to kill it anyways”) while others contend the cancellation was final from the hour it was announced. Whatever their true duration, any stubborn efforts to keep toiling away on the executed game were cut off soon enough when individuals were quickly reassigned or worse.

These image grids consist of the remaining “screenshots” to make their way onto the internet, all courtesy of Karen Purdy’s portfolio. The first four images above depict the backstage area of the high school dance in the first episode, where a multi-part puzzle would have taken place. The second row finishes out with more of the DJ tent at the Burning Max festival from the third episode. A minigame would have figured into this sequence.

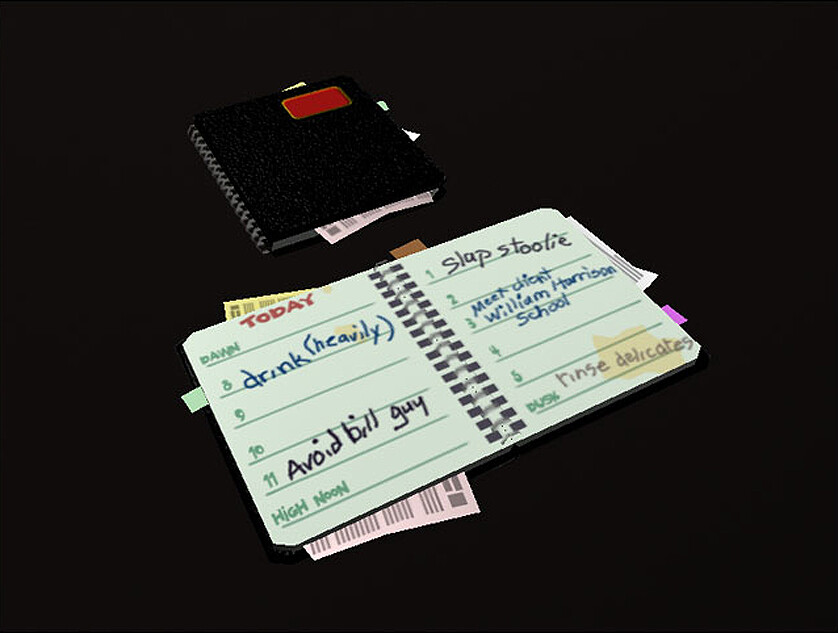

The first row shows the exterior and interior of a warehouse location from the fourth episode. The villain in the distance of the rightmost screenshot, who seems to be the same cat man that appears in the E3 trailer, can only be former child star II Gato Grosso. A precursor to Brady Culture in the Telltale incarnation? The second row appears to consist of a glimpse of Flint Paper’s memo book and his office. Note The Maltese Falcon poster parody above the bed.

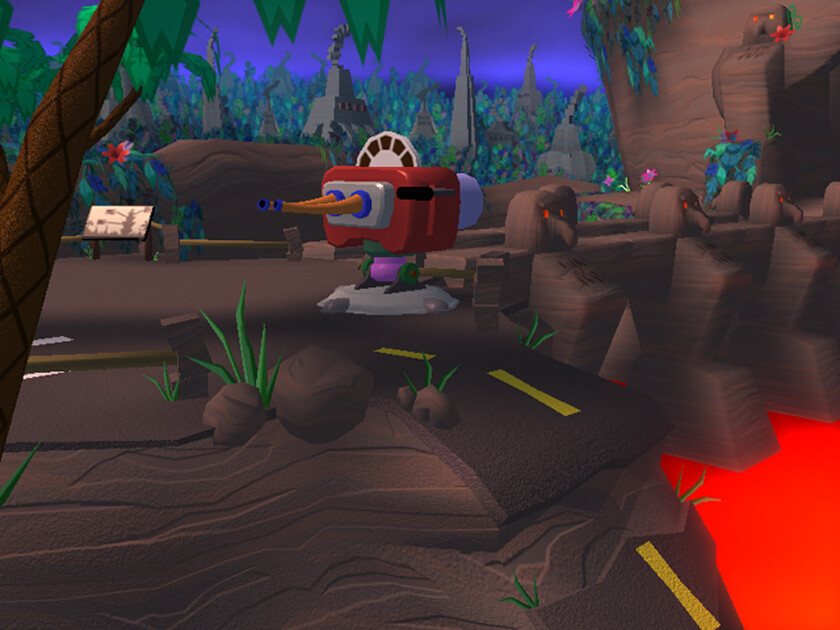

The first row gives us two screenshots of the space station FOOBAR from the fifth episode, and the exterior of a volcano-like spire that serves as the lair of uber villainess Penelope Gwinn in the sixth episode, set in the high priestess’s homeland of “Subarctica”. Sam and Max presumably gain access using that View-Master-looking doohickey. The second row gives us a look inside that spire (the grand climax?) and two additional looks at the recurring bassoonist and his traveling table.

The team, in summary, was understandably frustrated, saddened and demoralized, but they were all professionals about it. No such standards of decorum would alloy the fan reaction.

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo