- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

Introduction/Justification

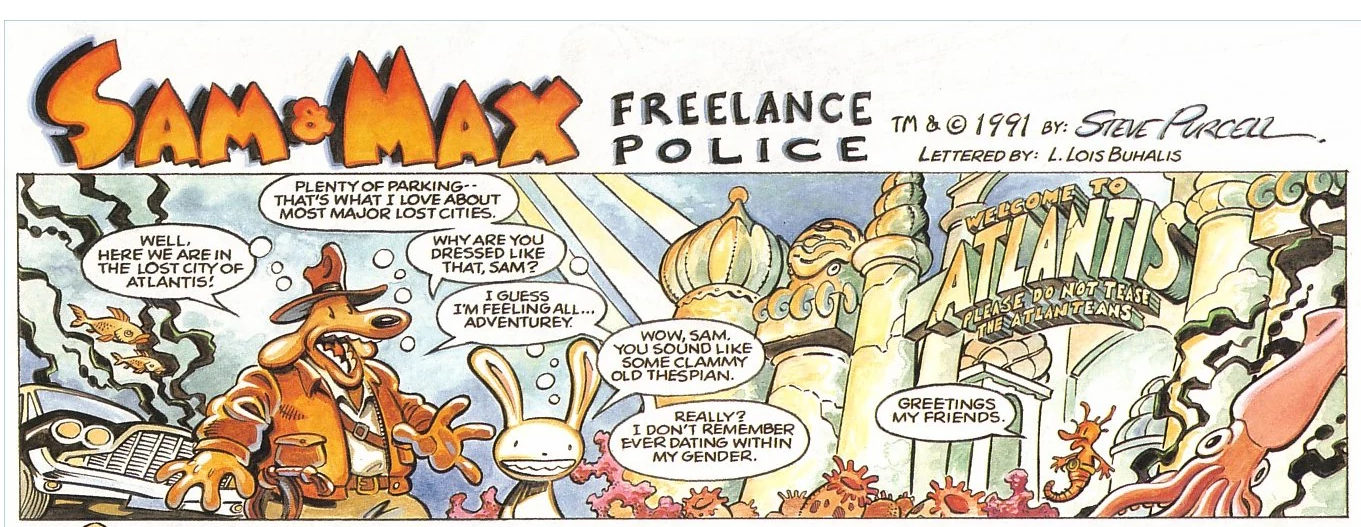

There were a lot of reasons not to write this feature. First of all, Sam & Max: Freelance Police is old news. Real old news. Fifteen Sixteen-year-old news, as a matter of fact. Few things can possibly appear more pointless than holding vigil for a cancelled computer game a decade and a half after the fact. A family of psychiatrists could retire on whatever disease drives Mixnmojo’s neurotic inability to move on.

Even without that distance, the credibility of a perspective from which the game’s demise is especially worthy of grief would seem a challenge to argue for. The wound inflicted on the Sam & Max fan base in the spring of 2004 was more than reversed when Telltale Games was founded, licensed Steve Purcell’s characters, and started making its own Sam & Max games with much of the cancelled game’s disbanded team. Which was almost immediately.

The fact of the matter is, things worked out. While what happened to Sam & Max 2 sucked, and it represented a colossal, appalling waste of talent and effort, we’ve got more to show with Telltale’s subsequent three “seasons” (effectively three full-sized adventure games, each better than the last), and the attendant Sam & Max resurgence in a general sense (taking the form of new and re-released strips, a home video release of the animated series, various merchandising and more) than we ever would have gotten out of turn-of-the-century LucasArts.

For even if Sam & Max 2 had been released to success, LucasArts was at that point bound past backing out to becoming The Star Wars Licensing Office, Please Hold. In retrospect, and perhaps even in the moment for those capable of reading the situation with the proper cynicism, it was never in the cards for the company as it existed by that juncture to reclaim its status as an exceptional development studio, much less furnish Purcell’s underground comic strip an interactive future -- however affectionately the morally ambiguous crimefighters may have been coupled with the division’s early history.

Besides which, what the hell else is for there to learn? Fifteen years was plenty of time for any retrospectives to come out (and there have been some good ones), or for any last bits of media to reach sunlight, or for any handwringing that fans can still find the energy for to claim potency or solicit commiseration. Our own messy but exhaustive informational round-up article, published years ago, seemed as close to a final word on the subject as anybody in its brutally limited audience could reasonably expect.

And yet here I am, dutifully marking the latest anniversary. But as you’ve probably gleaned from the page count, I’m not just here to lay another bouquet on the grave. I think there remain a few assumptions to correct, and more substantially I think there remains a story to be told. Sam & Max 2 may be a dead horse in terms of its own, self-contained history, but there’s a bigger history it plugs into - an overarching saga as pertains to LucasArts, Telltale, perhaps the industry as a whole and, in a self-interested but nonetheless profound sense, this web site.

It’s a context that hasn’t been fully appreciated or examined, even by the most well-meaning and researched of LucasArts retrospectives, a bundle of which were published in the wake of the studio’s effective shuttering in 2013. Take this excellent piece by Game Informer chronicling the last decade of the company, which, far from acknowledging the fallen graphic adventure as a turning point, fails to mention the project whatsoever, preferring instead to chart the studio’s decline almost exclusively in relation to its Star Wars products. But as a repudiation of its own legacy, LucasArts’ cancellation of Sam & Max 2 was a defining act and a flashpoint moment, the nucleus of a lot more than what has ever been collected in one place, and I think the passage of time has only made this comprehensive reading more credible.

The forces that initiated Sam & Max 2 and the circumstances which felled it in many respects tell the story of LucasArts as a whole. It was a studio that began with an almost fairy tale like existence, its initial decade characterized by unfettered creativity, a near-absence of pre-existing IP and an unusually relaxed fiscal culture. (“Don’t lose money” is how designer Noah Falstein remembered George Lucas setting revenue expectations for the division.)

Its second decade saw its negotiated entry into the real world, where the maximization of profits finally had to be given more than cursory consideration -- a voyage that access to the Star Wars property certainly aided in navigating. It was a decade of mounting identity crisis, an attempt to strike a balance between product that was a reliable moneymaker and the ethos of bold invention that the company was built on.

By its third and final decade, which Sam & Max 2 was significantly greenlit at the start of, the fight had a clear winner, and the years that remained were a slow, undignified but certain transition to the company’s final form as a logotype in Bob Iger’s billfold.

If it represented an end point for LucasArts, Sam & Max 2’s cancellation was just as convincingly an impetus for a number of subsequent endeavors. The most obvious is Telltale Games, but there is room to argue for a larger, cascading effect. What Telltale was abetting in was no less than the mainstreaming of a digital marketplace, a now dominant platform which has allowed developers to meet a niche audience directly and nimbly, turning games that were nonstarters under rigid, outdated business models into modest yet viable business propositions. Telltale did not alone popularize digital distribution, but it certainly led by example when it came to forging a sustainable template for interactive stories.

You can’t, for example, realistically separate what Double Fine was able to achieve with their historic Kickstarter (and what that in itself forecast) and the foundation Telltale had laid with their earliest direct-to-customer successes. And since there is no Telltale without the demise of Sam & Max: Freelance Police, which reputedly began its life with a pitch by its team to distribute Sam & Max “cases” over the web, the thesis that this saga commenced with unrest in the Balkans at LucasArts has some merit. And it would be difficult to even begin to explain, to the few who would care, how the game’s fate impacted Mixnmojo, which also exists in its current form as a fairly direct consequence of the events of 2004, including the dispersal of most of its original staffers into the games industry itself.

In other words, it’s all related. While the following ten (!) pages of disaster tourism are rife with my own speculation, the facts make a case that Sam & Max 2, however niche a topic unto itself, was a catalyst, a splash, one with wide-ranging reverberations that are felt to this day, even if they have not necessarily been understood in relation to one sacrificed point ‘n click adventure game.

As part of the research for this article, new interviews were conducted with various members of the Sam & Max: Freelance Police team and other relevant players whom we were able to track down and successfully hassle into tearing off the scabs. I thank everyone who participated for their time and their candor, which proved crucial in allowing a story to emerge that feels more complete and closer to the truth than any version that had been pieced together before.

That story, as I see it, begins in the 1990s.

The International House of Mojo