Part 5: The only game, really

It might be wise at this point to underline what should already be obvious: this article is written from the point of view of a fan base – the kind of subset that is often politely dismissed as “small but vocal” – that was by now more than wary of Star Wars games and deeply disappointed about the corresponding lack of attention to the legacy titles and investment in new experiences.

It’s a point of view that gets underrepresented in LucasArts retrospectives despite arguably being the one more equipped to evaluate the studio’s thirty-year history as a whole (as opposed to the view that the company’s enduring contributions to the world were Knights of the Old Republic and Battlefront), but it would be a mistake to frame it as the view of the rank-and-file gamer of the time, or even of today. People were and are buying those Star Wars games, after all. “Star Wars Interactive” as a company identity wasn’t exactly working out badly for anyone maintaining the ledger book.

(Even Star Wars fatigue ascribed to the developers, who are to state the obvious individuals rather than a hivemind, may have been over-speculated, with Mike Stemmle pointing out that he himself harbored a desire to play in the Star Wars universe over his long career at LucasArts, eventually getting to do so fifteen years in by sheer “inertia” after Sam & Max 2 fell apart.)

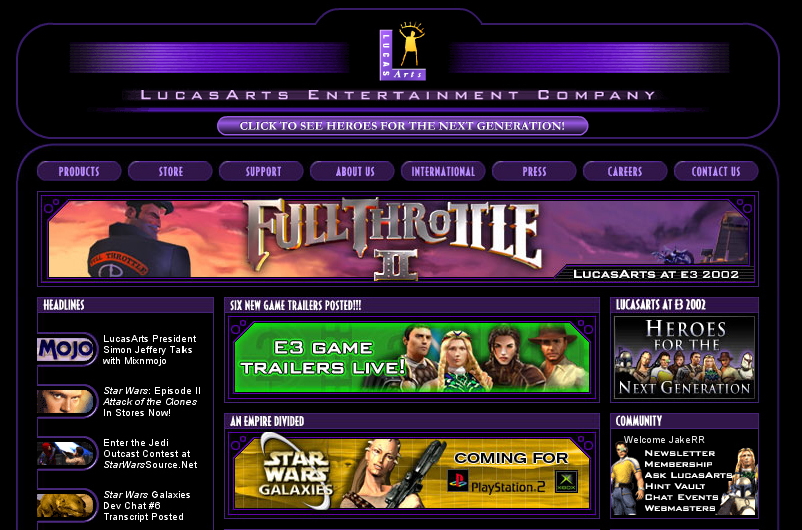

When the LucasArts lineup was revealed at E3 2002, Mixnmojo’s coverage was wide, but the aim of its most genuine excitement was narrow. The site was pleased and intrigued to see the original titles on display, particularly Planet Moon’s Armed & Dangerous, but there seemed to be little in the way of a real valentine to the fans, and we were a little too sculpted by past antics to muster much optimism for most internal projects, even the ones that potentially deserved more of our support. On the other hand, LucasArts would go on to mostly validate the most skeptical view of their inhouse titles. Of the Star Wars games, the most promising ones were pointedly the work of third parties, such as BioWare or Factor 5.

You would think that a sequel to Full Throttle would have garnered a similar amount of excitement as a sequel to Sam & Max Hit the Road (which, absent from E3, would not be announced until August 2002) around here, but Full Throttle: Hell on Wheels had a number of factors working against it. The first was protectiveness on the part of the original’s audience. A recurring objection was that Full Throttle 2 wasn’t even a graphic adventure – the response from the community to its unveiling as an “action/adventure” hybrid, to release on Xbox and PS2 as well as PC, made this quite clear.

As we’ve seen, Full Throttle 2’s genre-melding was rationalized internally as the only way to get the prospect to the stage of a green light, but the notoriously conservative adventure crowd wasn’t as tolerant of this direction as the developers had doubtless hoped would be the case. Those who would object to this characterization of at least the most vocal adventure gamer contingent as uncharitable or exaggerated are encouraged to look through the archives of the Adventure Gamers and Just Adventure forums from the time and get back to me.

“Action/adventure” in truth is a term that has been demonstrated to mean pretty much: anything. For adventure game fans, though, it carried connotations of impurity. Certainly, Full Throttle 2 was not going to be a point ‘n click game like the original, and that was enough to disregard the title outright in the minds of some. (It is a testament to this stubborn mindset that the control scheme and even the move to 3D had alone been enough to make some purists dismiss Grim Fandango and the fourth Monkey Island, which were full-blooded adventure games, out of hand.)

Even the wider press detected a lack of confidence in LucasArts turning to an, as Eurogamer put it, “old fashioned level based approach” with Hell on Wheels. And while Full Throttle as a universe is arguably quite suited to a sequel that blends genre mechanics more aggressively (goodness knows the action sequences attempted in SCUMM the first go round weren’t unconditional successes), it still meant that all the talk from LucasArts about revitalizing old properties really only came down to a single project where traditional graphic adventures were concerned: Sam & Max 2.

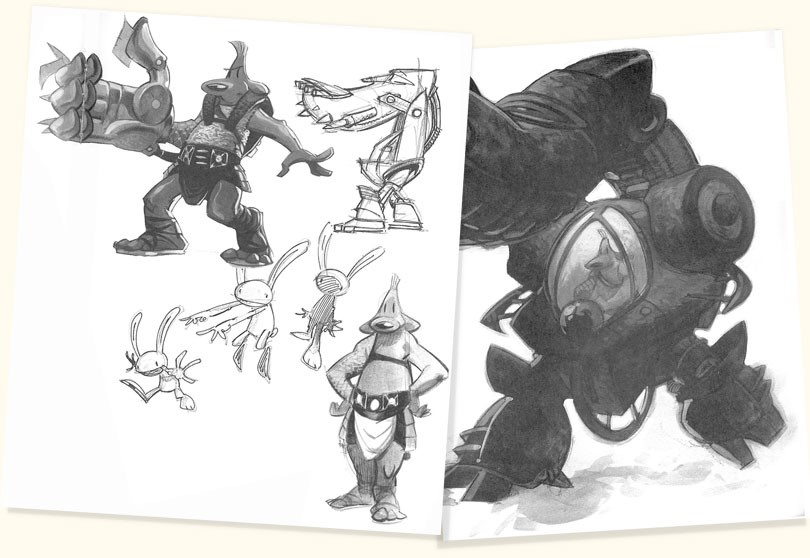

Full Throttle 2 also suffered from not having the support of its original creator. While Tim Schafer, who by then had already founded Double Fine Productions and was well into Psychonauts, didn’t explicitly denounce the sequel to his 1995 hit, it was made clear enough that he wasn’t entirely comfortable with it existing without so much as the courtesy of seeking his blessing – if it should exist at all. In contrast, Steve Purcell was enthusiastic about Sam & Max 2, which saw the return of Hit the Road’s Mike Stemmle as its project leader. (As pointed out, Hit the Road’s co-project leader Sean Clark, perhaps the only other proven adventure designer still on hand, was assigned to Full Throttle 2 at the expense of a more complete reunion.) Purcell himself had by then left LucasArts for a day job at Pixar, but he served a reasonably active role on Sam & Max 2 as a consultant, generating quite a bit of concept art and in general providing constant, valuable feedback on artwork, storylines and dialog. "Everything benefits when Steve's involved," says Stemmle of Purcell's input. "He's one of the better 'yes, and' guys I know."

Yet another mark against Full Throttle 2 was the death of its lead character’s voice actor, Roy Conrad, while Sam & Max 2 would deliver on the return of Bill Farmer and Nick Jameson for the title characters. Finally, Hell on Wheels simply wasn’t looking all that good. It was routinely mocked as Hell on Eyes by those put off by the early screenshots, and it seemed to be suffering from internal development problems that were endemic at the time. At any rate, it was running overschedule; the word from the grapevine was that it was facing down a six month delay after missing milestones.

As it was for the developers building it, Sam & Max 2 was for the fans an oasis, that elusive sequel that seemed like it was being made for the right reasons, by the right people. Its announcement was an especially unexpected treat for the Sam & Max faithful for its timing, as it had come off the heels of two sizable blows for the cult property it represented a revival of. A Sam & Max animated series produced in the late 90s was cancelled after only one season despite garnering a Gemini award, while a space-themed Sam & Max console game attempted by Justin Chin’s start-up, Infinite Machine, in 2001 - already eight years after Hit the Road - shared the premature death of the studio itself.

Around the same time, an animated Sam & Max short called “Our Bewildering Universe” appeared on the internet without explanation. Bearing the label “Lightsource Studios,” the Flash video was the work of a small team including Steve Purcell and another ex-LucasArts artist, Gary Winnick. It was a wonderful but confusing bit of Sam & Max content, as it was unclear what broader interests the one-off was related to. Eventually it came out that it was intended as part of a pitch reel for a weekly flash cartoon site that never actually got off the ground.

After all those Sam & Max near-misses, LucasArts’ announcement of Freelance Police seemed to signal the end of the characters’ string of bad luck, and in the hands of Stemmle’s team and under the guidance of Purcell himself, it appeared the odds of dragging the characters into the 21st century with their souls intact were as high as they were ever going to be. As Mixnmojo noted when it had nothing to go on but the game’s pedigree and Jeffery's aside that Stemmle had been sitting on ideas for a Hit the Road sequel for years, the motivation “at least sounds like the opposite of milking a franchise.”

All of which is to emphasize that Sam & Max 2 was, by the explicit admission of Mojo after its cancellation, “the last original game –and the only game really –anyone around here was genuinely interested in seeing.” From the studio the site ostensibly existed to write coverage for. It was a telling revelation of the growing disconnect between Mixnmojo and LucasArts that was in effect well before the atomic bomb that would sunder the relationship irreversibly.

And perhaps that consternation was a two-way street. “I just suspect there are people at LucasArts who don't like the site very much,” commented Jake in the aftermath. “There were the ‘anonymous’ forum posts a long while back about how Mojo is a totally biased rage machine and secretly actually hates LucasArts, despite its constant dedicated coverage for years.”

Another conflict was LucasArts’ ignorant and tone-deaf cease and desist against the then-nascent ScummVM – the painstakingly built and perfectly legal software that made old LucasArts adventure games compatible on modern operating systems. The still-invaluable solution amounted to fans doing the work of keeping LucasArts classics runnable when the studio couldn’t be bothered with stewardship itself. This effort was monumental, as it required reverse-engineering the games, while a LucasArts that was merely north of indifferent to its library could have done something similar much more easily due to access to the source code. Their energies in that direction were abortive at best.

The threat of legal action came to naught, but only after four years of gratuitous grief for the ScummVM crew. Today, Disney/Lucasfilm is only too happy to make use of the open-source software for their own benefit -- official releases of LucasArts SCUMM games through GOG and Steam come bundled with ScummVM as the default launcher, allowing the games to be sold on platforms they weren’t even written for without the property holder having had to lift a finger or spend one thin dime to make that happen.

But while relations weren’t always silky smooth between the studio and its catalogue’s most loyal devotees, Sam & Max 2’s announcement press release, coverage of which broke the record for most comments on a Mixnmojo news post, saw LucasArts speaking the fans’ language:

"Sam & Max Hit the Road is a classic and as close to being a signature game as any LucasArts has ever done," says Simon Jeffery, president of LucasArts "The Sam & Max sequel, much like the recently announced Full Throttle II, perfectly complements LucasArts' renowned adventure game legacy and lends further support to the company's commitment to investing in and developing more of our original properties.

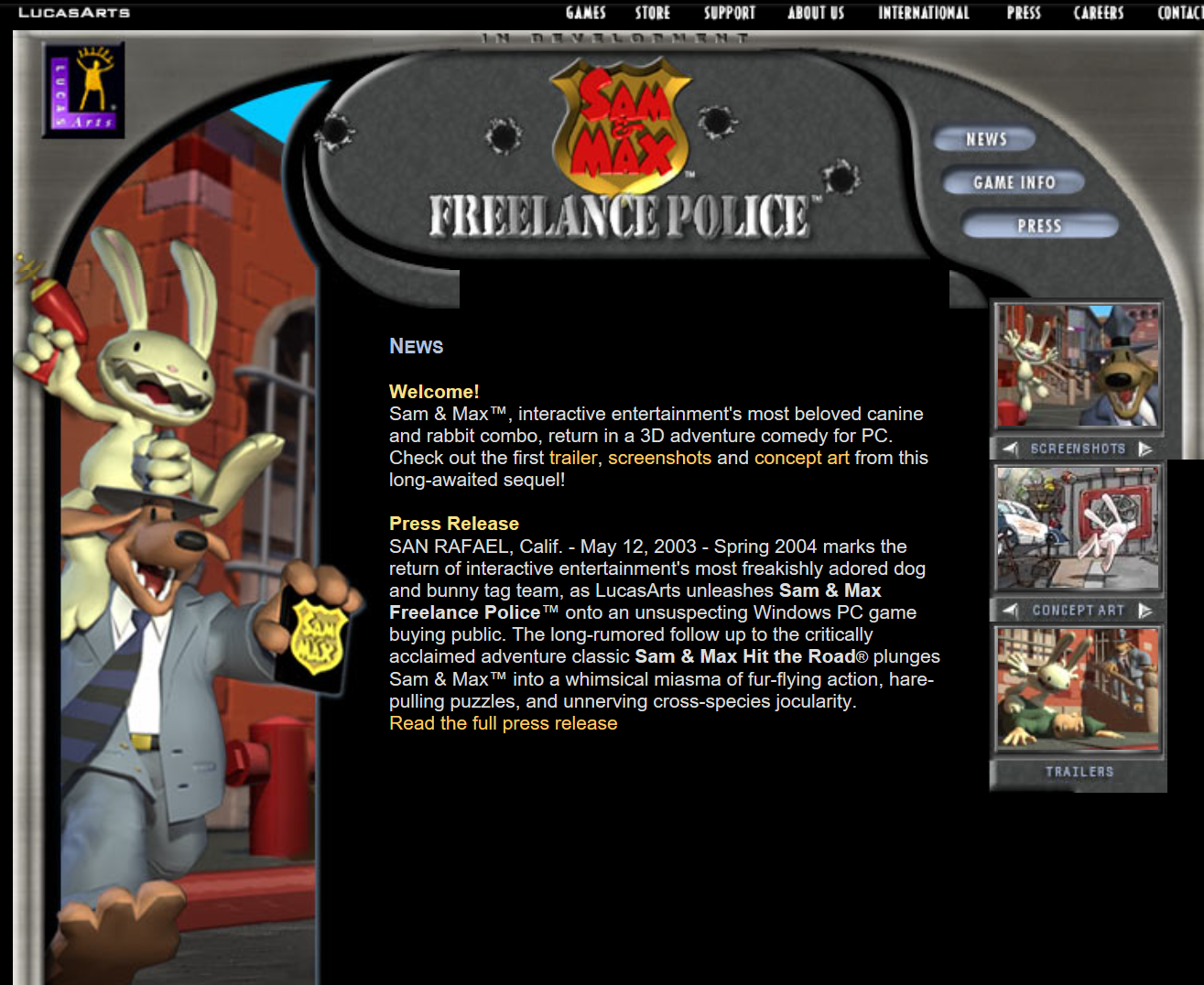

The problem with Sam & Max 2 was that it was the very last of the slate’s original games. Its projected release was still very far away (Spring 2004), and we had precious little to go on while we waited, other than the enticing promise that it would be the first LucasArts adventure game to sport real-time 3D presentation while restoring point ‘n click gameplay, as opposed to the pre-rendered, direct control approach of the studio’s earliest 3D adventure forays, Grim Fandango and Escape from Monkey Island.

Most of LucasArts’ upcoming projects had some substantial media to whet appetites with, but what we had in this case was: an internet splash screen, two screenshots (which would more accurately be called proof-of-concept renders and not entirely representative of the game’s eventual look), some concept art, and a lot of evasive PR-speak.

Image one and two: The first two “screenshots”. Image three: The official project web site for Sam & Max 2. Note the pluralization of the “Trailers” category, a promise which was never made good on. Kinda like the actual game.

And so we would have to wait, and occupy ourselves with the other titles that LucasArts had in the works. And hey, some of them looked pretty good!

- Page 1 Introduction/Justification

- Page 2 Part 1: Star Wars Interactive

- Page 3 Part 2: Brain Drain

- Page 4 Part 3: Simon Says

- Page 5 Part 4: A Welcome Oasis

- Page 6 Part 5: “The only game, really"

- Page 7 Part 6: Spot the Pattern

- Page 8 Part 7: “The smoothest project I ever worked on”

- Page 9 Part 8: General Shut-Uppery

- Page 10 Part 9: “I mean, kickass we got Slashdotted”

- Page 11 Part 10: Telltale Now

- Page 12 Parting Reflections

- Page 13 Appendix: Sources and Acknowledgements

The International House of Mojo