Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #3: Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade Second Review

Hi. I'm Jason. Welcome to my review.

Once upon a time, LucasArts (then Lucasfilm Games) neither developed nor published games based on their parent company's high profile movie franchises. It might seem unbelievable that what today could accurately be referred to as "The Star Wars Publisher" was ever capable of abiding that, but the fact is that in the first several years of the company's existence this practice was not only followed, but followed strictly. Lucasfilm would happily license the rights to Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Willow, and other properties out, collect the licensing fee, and let other companies exert the effort and assume the risk. With these film properties off-limits, the young but highly resourceful development studio devoted itself to the creation of new intellectual property that led both to its reputation as a team of creative visionaries as well as the attraction of lifetime fans (although admittedly March 2004 saw a lot of suicides).

Eventually, of course, the inevitable happened. When the third (and at the time, it seemed, final) Indy movie, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, was set to be released in the summer of 1989, it's only natural that the game division, who'd recently entered the realm of self-publishing, would want to take advantage of the event. Two PC games based on the film were ultimately commissioned, one being the awful and instantly forgettable "Action Game" (as it was subtitled), which was developed by a third party, and the other being the "Graphic Adventure," an in-house production and the game in question. Presumably this dual release, a strategy replicated with their next Indy game, was an effort by the company to adequately address both the "adventure" and "action" facets of the title character before such a time existed that the they could cover both bases with a Tomb Raider rip-off. Maybe it was just an attempt to cash in on the movie twice. In any event, while Last Crusade is not the company's virginal experience with a license (they'd developed Labyrinth for Activision a few years before, for example), it was arguably the first prominent example, and certainly the first example in which they were holding the publishing cards.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is a particularly interesting entry because it's the only LucasArts graphic adventure that is directly based upon previously existing source material. While both the removal and invention of story content is liberal, the game does roughly follow the narrative of the motion picture, and was in fact based on its screenplay - the screenplay, and not the finished film, since the game and the movie were parallel productions so that the the adaptation could hit store shelves at the most opportune time. Fans of the film will find many of their favorite moments revisitable in interactive form while playing this game, but at the same time it's an original enough experience that knowing the plot of the movie won't give you an advantage in getting through it. In order to accomplish the feat of making a decent game in what was even back then a challenging development period of seven months, the title was assigned three experienced project leaders: Ron Gilbert, David Fox, and Noah Falstein.

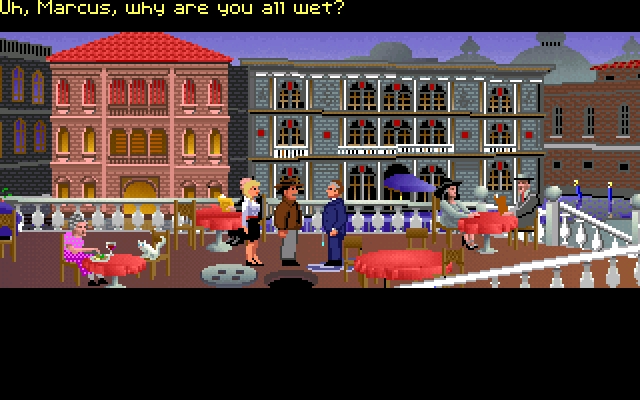

A three-headed creative director could have easily resulted in an unfocused game, but the impressive fact of the matter is that valuable and diverse strengths of the multiple directors seem to have benefited Last Crusade more than stymied its potential. The gameplay and even the tone offers a diversity - there are rather casual shifts between levity and seriousness throughout, yet it somehow never feels too jarring or schizophrenic. After all, a balance of gasps and laughs is one the movies themselves have to manage; it's a part of the license. Additionally, the game's handful of arcade-like sequences are incorporated in such a way that actually makes sense, and despite the over-the-top difficulty of most of them they're rather fun, and actually lend a sufficient degree of "action" to what is a pure graphic adventure. While Indy may spend the majority of his time thinking his way out of situations in this game, he uses his fists and his trademark whip to a fair degree as well. In the modern era, a traditional adventure game has proven to not be the preferred vehicle for this character by the folks running the garage, but I've got to say I think the balance that this game and its immediate successor achieve works a lot better, and is a truer representation of the franchise, than what Infernal Machine or Emperor's Tomb accomplished.

As part of its efforts to jumble things up a bit, the game also periodically breaks away from the usual side-view perspective by interspersing a couple of overhead sections when Indy is exploring large areas, specifically the Venice catacombs, Castle Brunwald, and the airframe of a German zeppelin. Some people have identified these sequences – incorrectly, in my opinion – as "mazes," though I suppose any area with branching paths and the inability to see more than a few feet in front of the character is ostensibly a maze on some level. Unlike the traditional mazes of Zak McKracken, though, these bits are more about exploration or sneaking past Nazis on patrol than figuring out where to go. Though they tend to be pointed to as a badly dated element, and they can certainly get a little too backtrack-heavy and overpopulated with enemies, I must admit I do enjoy these and all of Last Crusade's attempts to mix things up on the whole. The Three Trials finale in particular is immensely satisfying.

The SCUMM engine was noticeably revamped for this game, with a revised (read: reduced) set of verbs and the introduction of highly improved art and animation capabilities. In fact, compare a screenshot of this game to The Secret of Monkey Island and you will see very little difference in the interface aside from the eventually lifted "What is" verb. Whether you're playing the EGA or 256 color version of the game, you can see a substantial jump from the look of Maniac/Zak here. And you can finally "Look at" inventory and environment hotspots now, rather than being limited to reading signs or documents, which in itself invites more interaction with the game world on the player's part.

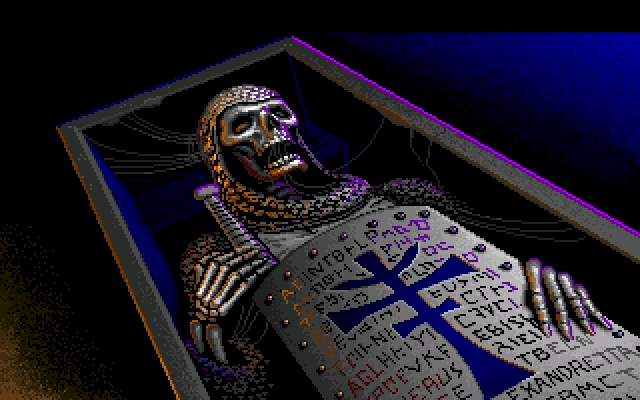

The character animation, barely north of existent in the first two SCUMM games, is also a huge step up - the sight of Jones swinging his whip or exploding as a skeleton courtesy of a fellow named Steve Purcell is still pretty impressive today. This is also the first LucasArts game to employ detailed "close-up" shots that would be hip over the next few projects. These include an up close and personal glimpse of the skeleton of Sir Richard and his shield, a moment that arrives complete with a dramatic chord, creating a moment which may or may not have scared the living snot out of me as kid.

The innovations do not end there. This is also the first LucasArts game to feature the iconic dialog trees, though unlike future games most of the dialogue is not there for fun, but is rather a fiendishly disguised puzzle, and you very much have to pick the "correct" conversation path or face the usually harsh consequences. Still, even if playing through these scenes is often a stressful and trial-and-error based experience, the multiple solutions that they offer is impressive – there's usually a way to talk yourself out of a conflict with an opponent character without resorting to fists.

In fact, something that absolutely must be brought attention, and is something I pointed out about Zak McKracken, is how many alternate ways the designers provided to get you through what is by and large a linear game. Getting my hands on the game's official hintbook, which was tragically an event that only transpired after completing the game the hard way, did a lot to enhance my appreciation for what this game must look like on the drawing board. Who knew there was more than one way to solve so many of the puzzles, or that there were so many nonviolent tactics to get past Nazi guards? There are a ton of alternate solutions in this game that you could never possibly know about with a single playthrough under your belt.

There are even a few sections of the game that you will only see if you take a certain route. Take, for example, Indy's maneuvering across Castle Brunwald's exterior in a lightning storm, which you'd completely skip over if you opt not to exit a room via an open window. For years, I thought the little scene existed only in the game's non-interactive demo. Another example is an lengthy, grueling sequence aboard a zeppelin that can be entirely avoided (or criminally skipped, depending on your perspective) if you had the foresight to swipe a biplane manual in the Venice library earlier on in the game. And if you are sharp enough to give Colonel Vogel the fake diary instead of the real one when he forces Indy to hand it over, there will be no need to swing by Berlin and meet up with Hitler in a classic moment later on in the game. (On balance, this decision robs you of the chance to get a tremendously useful item, as I learned in an agonizing replay that corrected my assumption that I know the game like the back of my hand after all these years.)

The game also introduces "IQ Points," an unobtrusive but somewhat confusing feature which are categorized attempts to tally your puzzle-solving accomplishments in some quantifiable way. This Sierra-like scoring system of sorts might make you feel better about yourself or serve as a motive for subsequent playthroughs, but the values you earn can be nebulous in their maximums and reasons for being awarded, and I don't think anyone cried too much about the fact that Last Crusade's immediate sequel was the only game to retain it.

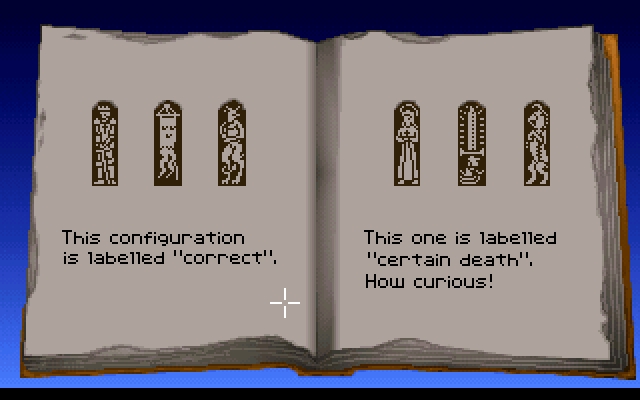

A unique flourish that must be mentioned is a physical companion to the game in the form of Henry Jones' Grail Diary, as featured in both the game and the movie. Coming packaged with the original releases, this rich text is filled with background, hints and even some information that is imperative to knowing which chalice to choose at the end of the game. (This spelled disappointment for those who pirated the game or lost their tome.) More than anything though, the book, penned by Noah Falstein, contains all sorts of fun miscellany and is a work of art in and of itself, remaining one of the coolest "extras" to ever be packaged with a video game. Re-releases of Last Crusade came with a more budget-minded version that sadly lost a lot of material (the original book was between 60-70 pages), and nowadays the most available option is a decidedly less romantic PDF.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade is arguably the last of the pre-Monkey Island SCUMM entries that requires the lens of context to forgive some cruel-minded roughness in the design philosophy. The central issue, despite being a vast improvement from Zak McKracken, is its frustratingly high difficulty. The matter is not improved by the inclusion of death possibilities and dead-ends, with this game being the last intentional example of the latter in a LucasArts adventure game. I have a friend who will never touch this game again because he ran into an unfortunate situation where he needed an easily overlooked wrench that it was no longer possible to retrieve. In experience, consensus sees the graphic adventures they made up to Monkey Island as LucasArts' formative SCUMM titles, and Last Crusade represents the final stone to the river bank of a winning formula. (The simultaneously developed Loom's kind of a different beast altogether, but we'll get into that next month.)

The most common complaints, however, are focused on the action sequences, which are not strictly forgiving in nature. The keyboard-controlled fistfighting element, which is necessary to some degree to get through the game (though as mentioned can be avoided under many circumstances if you're clever about it), can be very difficult to perfect, which poses a problem in some sections, particularly the stretch in the Zepplin scaffolding where there's about a hundred and fifty Nazis too many on guard for the welfare of most people's patience. While most of the time mashing the numbered keys will get you through a fight, this will not help you in every scenario, especially since Indy's stamina does not replenish after each fight. When an adventure game integrates action elements, it's probably appropriate that it does so in a way that doesn't require too much dexterity and practice, and the game slightly fails on that front. (Last Crusade's successor, Fate of Atlantis, addresses this problem by pulling the difficulty of the fights in the complete opposite direction.)

The other action sequences, such as a numpad-abusive aviation bit in a biplane are more fun if not much less difficult. Overall, the game's flaws are minor at best and bearable at worst. Taking the year of release into account when looking at these older games as I think is apt to do, you'll generally find a lot more to admire than to rant about.

The Last Crusade is a solid, worthwhile graphic adventure and probably one of the better movie-to-game adaptations ever made. While some shortcomings emerge in the form of outdated design sensibilities, the game is above average and an absolutely imperative presence in any self-respecting LucasArts fan/adventure fan/redeemable human's library. I can't tell you for a fact that choosing to not play this game will result in your rapidly aging in a deliciously cheesy first attempt at digital compositing by ILM but really, why risk it?

Written by Jason, who was about as fortunate as Indy when he elected to punch Hitler in the face in front of machine gun-equipped Nazis.

Four out of five Murray skulls

Pros: Both does justice the movie and stands on its own two feet; successful blend of adventure and action; pretty impressive design; lovely art and animation; you get to punch Hitler.

Cons: Dead-ends blow and make the game’s already high difficulty less tolerable; fistfighting is near impossible to master; where the hell is Sallah?