Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #13: Grim Fandango Our Review, Part Dos

At its core, the gameplay of Grim Fandango isn't really a deviation; inventory puzzles and dialog trees remain the method of advancing, with the changes being mechanical. With a conventional interface gone, the player controls Manny with the keyboard, the arrow keys acting as his steering wheel and the shift key functioning as his accelerator. (A camera relative control scheme is also offered to accommodate a joystick/gamepad.) As the presentation renders hotspots less obvious than they once were - Manny's head will turn or tilt to face an nearby object if it is interactive - a key press will superimpose text over all hotspots in the room to ensure that pixel hunting remains a bygone irritation.

Actions for picking up objects, examining objects, using/talking to objects/characters, and pulling out inventory are also assigned to respective keys, with inventory simply being a matter of the game cutting to Manny's coat and the player cycling through his collection, which always begins with his trusty scythe – his equivalent to Indy's whip. (Like Full Throttle, item combination is forsaken.) The result is a fantastically immersive, streamlined experience but with some undeniable control issues. Moving Manny around can be awkward at first, and the occasional glitch (mostly in the form of the game's infamous elevators) can result in the frustration of Manny bumping into a direction the player did not intend for him to go.

Additionally, while removal of the sentence line succeeds in purifying the screen, dark environments and the subtlety of Manny's head movements often makes it necessary to rely on the aforementioned "reveal the hotspots" feature anyway, to ensure that you're not passing something up. Confusion is also a risk when it's required of Manny to simply "use" an object he is carrying on its own, an action that can only be accomplished if Manny is holding the object in his hand while also not standing in the vicinity of something in his environment that can be interacted with. Overlooking this can lead the player to think they've attempted a puzzle solution when they have not and proceed to waste their time pursuing other ideas. This is an unfortunate case of the player struggling against the gameplay mechanic instead of the puzzles themselves - the very issue that fueled Ron Gilbert's decision to eliminate parsers in the first place.

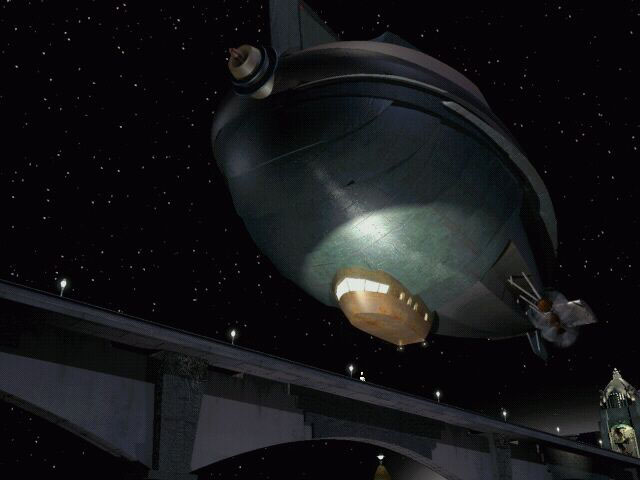

Still, Grim Fandango's intentions are pure and the execution is merely imperfect. The flaws of the new controls are a fair trade-off for the presentation they help support, and overall they're given more of a bad rap than they deserve, mostly from people who would stubbornly consider the inclusion of a point 'n click interface in an adventure game non-negotiable. The team's bold, progressive vision results in a game so cinematic that the many pre-rendered FMV cutscenes (conveniently replayable from the menu after they are first triggered) necessary only for the more dynamic camera work. Heck, the game is so proud of its cinematic aspirations that, in one if its coolest features (also found in the menu), it actually transcribes the game on the fly in screenplay format as it is played.

As expected, the sound is a tour de force. To estimate that the voice acting, directed by Darragh O'Farrell, is at least as good as in The Curse of Monkey Island (which O'Farrell also directed), speaks volumes. The large and feature-quality cast, led by Tony Plana as Manny Calavera, is brilliant, with actors that perfectly fit their roles all across the board. The delivery is always spot-on and even the accents are genuine. Similar kudos are owed to the game's soundtrack by Schafer's preferred composer, the great Peter McConnell, who delivers a score that is possibly his best work, much as Land was arguably at his finest with The Curse of Monkey Island. The music is an irremovable part of the game's atmosphere, and it holds up superbly on its own as well. (Like The Dig, it even received an official, abridged soundtrack release.) The tracks reflect the varied and at times strange settings of the game world, with live instruments employed to optimal effect. They also kick ass.

Strangely, it's the puzzles in Grim Fandango that are probably its weakest aspect. I say "strangely" because the puzzles in an adventure game are hugely important, integral elements that the title can live or die by. The obstacles here feel almost in the way at times, which is partly a testament to the strength of the story, but is also a reflection of logic that is sometimes reaching. To be sure, Grim Fandango's puzzles are the design of seasoned professionals, but they're also often unnecessarily difficult, and in some cases, impossible to make sense out of until after they're solved. It's not quite on The Dig level, but it is uncompromising.

An epitomic example is a meaty puzzle from Year 2 involving the search for an incriminating photograph. In a sense it's one of the game's best puzzles because of how layered and cleverly woven it is (bearing some similarities to the spitting contest of LeChuck's Revenge), but it's also just brutal and inane from a logical standpoint. It's a shame to think that many gamers were unable to enjoy the Grim Fandango's worthy and sprawling story due to its regularly old-school puzzle mentality, which succeeds in being enjoyable but is accessible with less consistency. And although the game's length is justified by the depth of its content, an extended sequence in the Petrified Forest near the beginning of the game feels a little like padding.

And as polished as the game is for its epic size and brand new engine, it's not without some hitches, and that does not exclude show-stopping ones. A problematic forklift was addressed after initial release with a patch, but I still can find myself stuck in the game when fiddling with the direction of a conveyor belt or interrupting the removal of a crane chain in Year 3. Saves in this game occasionally need to be made out of more than convenience.

What flaws the game may have, however, are incapable of making any real dent in its stature. I mean, it's Grim Fandango - the game's brilliance needs no justification for people who've completed it. I could go on forever, myself, gushing about the peerless grandeur that the game manages to achieve, or airing my appreciation for its cavalcade of individual moments, like the plaque to Beloved Sanspoof, or Glottis' ode to the Bone Wagon. Grim Fandango's strengths and flourishes are numerous, and while it's writing may be what rises to the top, it feels silly to single anything out considering how top notch every facet of the production is - this is one of those games, not unlike a number of LEC's best work, where every member of the team was at the top of their corpus. A masterful, original game that is a showcase all across the board, there's really not much one can say about Grim Fandango that hasn't been said by others more eloquently. No one should find themselves having never played it.

And yet, these people exist in large quantities. Heavily embraced by critics upon its release (the game won Gamespot's 1998 Game of the Year award which, considering that site's mainstream bent and Grim Fandango's genre, is remarkable), sales nevertheless did not exceed LEC's expectations, and for that reason it, along with the simultaneously developed The Curse of Monkey Island, are generally seen as the last hurrah of the adventure genre's huge-scale productions. Incessant claims that the game was a flop have been refuted by Schafer, who claims that it was profitable, but there's no doubt that the game fell short of being a blockbuster or a particularly impressive return on its not insignificant cost.

In retrospect, there was an inevitability to what Grim's impact signaled. The graphic adventure genre was getting, to quote Chief Bogan, too big for its britches. It's not that adventure games stopped selling, as is commonly assumed, but rather that they always sold the same amount to an audience that also remained static. Adventure games were a significant part of the early days of computer gaming, the industry's audience was a dedicated but modest group when compared to the makeup of today's market. Indeed, while other genres exploded in the mid-nineties, with their install bases growing rapidly - even exponentially - adventure games were neither growing nor shrinking. They simply failed to keep up with the rising costs.

The expensive, three year endeavor that was Grim Fandango, then, was not some singular, disastrous bomb that single-handedly decimated adventures; it was simply one of the more obvious indicators that the genre could no longer compete in the marketplace without reducing the ante, and that unconditional critical love does not necessarily translate to equally spectacular sales. Some healthy denial notwithstanding, the adventure faithful who loudly bemoan the loss of the grand, big-budget spectacles of the nineties have been slowly coming to this realization. The genre, of course, has never died, but the likes of The Curse of Monkey Island and Grim Fandango no longer exist with regularity because they can't, for reasons that are simple and mathematic.

Today, adventure games have evolved to not only survive, but to stay relevant and awesome thanks to companies like Telltale (which houses a few Grim veterans). At the time of Grim Fandango though, the excellence of the adventure games LEC was slowly putting out, much slower than was once the case, contrasted with the dire state of the company. With the release of a little movie called The Phantom Menace looming on the horizon, the then-president Jack Sorenson, or whoever powered him, saw fit to capitalize on the movie's publicity wave by commissioning eight hundred billion tie-in games, many of which were terrible, but all of which inevitably sold through the roof.

With a line-up of almost exclusively heartless Star Wars games to toil away on, it came as no surprise when the company's most vital creative talent left for greener pastures, either gradually or in droves. The effects of these losses were not immediate, which is why it was possible for the company to be putting out some of its best products while the clouds were darkening, scheduling a storm that would let loose during Simon Jeffrey's reign.

As for Schafer, he took a healthy break after Grim before returning to work on an action/adventure "spy game" for the Playstation 2. This console game didn't get very far before Tim and a large chunk of the Grim team departed and formed their own studio, Double Fine Productions, in July of 2000. There they made their own console game, the excellent and story-driven action/adventure Psychonauts. Meanwhile, LEC showed very little interest in the adventure genre after over ten years of putting out its all-time best entries.

This is not the article to talk about the end of LEC's days as an adventure developer, however. Although Grim Fandango was the final original adventure title from the high profile studio, and certainly in competition as the best, there was still one last brain-teasing story game ahead from the people who wrote the book on them. For Grim Fandango's part, its sales and the cold business realities surrounding its role in the legacy of its genre are dwarfed by its other associations. You might know them in the form of such words as "classic," "masterpiece," and, oh yes, "art."

A review by Jason, who at the Christmas party at least stayed down.

Five out of five Murray skulls

Pros: It’s Grim Fandango

Cons: There are some technical frustrations; puzzle logic can get rather “out there”