Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #13: Grim Fandango Our Review, Part Uno

For all the praise that gets lobbed in Tim Schafer's direction, the industry veteran is rarely given enough credit for his active efforts to evolve, rather than simply excel within, the graphic adventure genre. He's commonly thought of as a great creative mind and talented dialog writer (both entirely true), but there's also something of a design odyssey to observe in Schafer's string of story driven games that is significant and influential, and it continues to this day, despite the fact that his modern games have not always neatly fallen under the traditional adventure game umbrella.

If you compare the gameplay of the first two Monkey Island games to Day of the Tentacle, that to Full Throttle, and that to Grim Fandango (and even, arguably, from Grim to Psychonauts) the progression is obvious – Schafer was moving his games toward streamlined interfaces and more cinematic presentation. For evidence of the former see the way Day of the Tentacle allowed inventory items to be used as a cursor (pretty much obviating the verbs), or the way Full Throttle reinvented the interface altogether, reduced the volume of the inventory and pitched the idea of inventory combination. For evidence of the latter, look at the way the entire screen was devoted to the game world in Full Throttle and how the presentation-minded implementation of action sequences and music made cutscenes and gameplay feel closer to one and the same than ever before.

Grim Fandango takes things a step further by doing away with the cursor itself and adopting a direct control method in which the character is "driven" by the player. The contextual relevance of how this was arrived at is, I feel, lost on many who've played and enjoyed Grim Fandango. Although in my experience Grim Fandango has never met a player who didn't think it was a phenomenal game, the keyboard based control system (a mold-breaker which abandoned the trusted point 'n click interface LEC had pioneered and used since Maniac Mansion) is usually cited as a blemish on an otherwise beautiful painting, an arbitrary decision to fix something that wasn't broken in the first place.

This accusation is, quite frankly, ridiculous. Although the controls of Grim Fandango are far from perfect, it's quite clear that the intentions behind them had to do with storytelling rather than changing things up for change's sake. The world of Grim Fandango is one that players are invited to experience in a way more immersive and cinematic than any adventure game that had come before it. There is no cluttered visual interface serving as a divide between the player's input and Manny's actions because Manny is the interface. It's not insignificant that this is also the first LucasArts adventure where terms like "camera angles" and "shot composition" are actually relevant. Although the game includes a large number of pre-rendered cutscenes, the gameplay itself has qualities of an interactive cinematic, thanks to a beckoning, finely crafted 3D world where the designers were allowed to make the sort of visual decisions that a traditional film maker might when blocking a scene. With every game he designed, Schafer was removing the boundary separating the player and the rich world that he was meant to be absorbed into.

But I'm getting ahead of myself here. After finishing Full Throttle in 1995, which enjoyed great commercial success, Schafer was considering what his next project would be. A huge fan of Warcraft at the time (who wasn't?), he actually entertained the notion of making an RTS, but decided against it in favor of continuing to work within the genre he was known for. Knowledgeable of Mexican folklore from college courses and the owner of an art book which featured Day of the Dead skeletons, Schafer decided that he wanted to create a world in which these characters could walk around and live their lives, whatever that would entail. Around the time he was formulating these ideas, Schafer attended a local film noir festival, and a light bulb switched on in his head. The result was a melding of these two inspirations, leading to the inception of a world where the punchy writing and twisty plot of a hardboiled crime movie was married with an arresting visual style and a dense mythology which takes its roots in Mexican folklore.

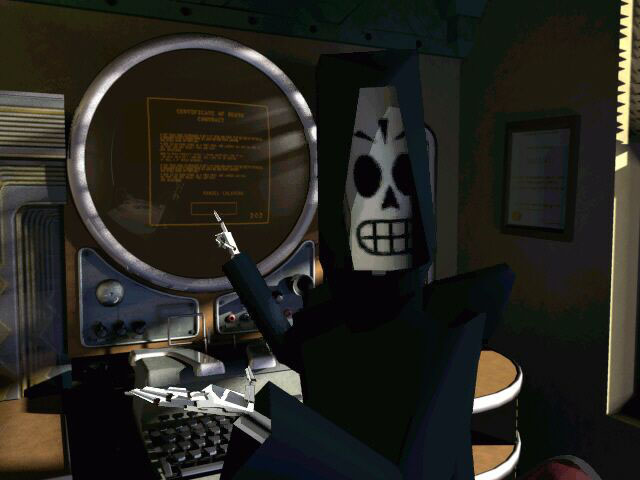

Bizarre but brilliant is an apt way to describe this blend, and it's a description that feels accurate to the game overall. It's not in any way obvious why a story that combines gritty crime fiction and Day of the Dead skeleton characters should work, but Grim Fandango's execution makes it seem like it should somehow always have been. The folklore influences come mostly from the game's art direction as well as the general premise - the setting is an interpretation of the afterlife, and the inhabitants look like paper mache skeletons. The plot and the plotting flavors this stage with film noir trademarks, from the sharp dialog to the femme fatale to the visual composition to themes of corruption and crime. There's also a bit of Casablanca thrown in (snooty French officers and fez-wearing fat men are abound), there's a healthy dose of Chinatown, and Manny's profession seems as much a tribute to Glengarry Glen Ross as Double Indemnity.

The scope is epic (the game, as long as any LEC adventure, takes place on four Day of the Dead's across a four year period) and of course, that trademark Tim Schafer humor. The designer's hand is arguably as evident in the game's implicit attraction of getting to be the (or a) grim reaper as well as an underlying obsession with over-the-top hot rods, which along with the state of the art nature of the technology theoretically lent the title marketability. It all improbably yet marvelously comes together into an incredible achievement that continues to boggle the mind and win the hearts of even the most cynical of gamers, many of whom sadly missed out on the game when it was initially released.

The curtain rises in the Eighth Underworld, aka The Land of the Dead, where Manny Calavera is a reaper working for the Department of Death. He is like an insurance salesman of the afterlife – his job is to greet newly deceased souls and attempt to sell them a travel package that will send them off on their journey through the Land of the Dead, the "Four Year Journey of the Soul," which ends with passage to the Ninth Underworld, The Land of Eternal Rest. A soul's ability to buy a certain package is dependent both on the amount of money their body was buried with (a Mexican folk tradition) and their eligibility based on how good a life they lived. The packages range from being shipped the long way by cramped parcel, to being given a walking stick, to qualifying for a double-n ticket on the Number Nine, an exclusive express train that makes the usual four year trip to the next life in a mere four hours. As Manny puts it, the ideal customer for a reaper is "a rich, dead saint."

It is unclear what Manny did to deserve his fate of "working off his time" through employment with the DoD, but he begins to notice that his customer's qualifications according to the computer do not reflect their records. A crack salesman who was once on top, the game opens with Manny struggling to get even the most lowlife of clients while his coworker and archrival, Domino Hurley, racks up premium sales with some obvious inside help. Although he has an ally and friend in his secretary Eva, Manny knows he's being played for a sap by his boss Don Copal, who himself is controlled by a "bigwig from the city," the sinister and rather rotund Hector Lamanz.

Like main characters in a noir usually do, Manny uncovers and gets pulled into a vast web of corruption the leads him into recruitment (the second recruit, to be exact) by an underground revolutionary movement called the Lost Souls Alliance, spearheaded by one Salvador Lamonez. Manny reluctantly accepts Salvador's offer, as it grants him the freedom to escape the DoD and embark on a quest to rescue Mercedes Colamar, a woman Manny inadvertently put into exile when he attempted to scam the DoD at their own rigged game. Befriending a big-hearted (in more ways than one) and fiercely loyal demon mechanic named Glottis, Manny spends his own four year journey traveling across the vast and varied landscapes of the Land of the Dead (including The Petrified Forest, the quaint town turned mob town Rubacava, the bottom of the sea, and even the Edge of the World itself), using his natural knack for rising to the top of his situation whenever he finds himself settling down. He soon uncovers proof that Hector's dark plot runs far deeper than he imagined, and learns that the rightful owners of double-n tickets are being cheated out of their deserved destinies.

Grim Fandango is a huge game full of ambitious ideas, and to realize them brand new technology was developed in conjunction with Lucasfilm's special effects studio Industrial Light and Magic. This was to be LucasArts' first 3D adventure game, and in their long term investment they pulled out all the stops. The SCUMM engine, used to power every LucasArts adventure game since Maniac Mansion was finally abandoned in favor of a new one ("GrimE"), scripted in LUA. Capable of rendering 3D characters on the fly and displaying locales in cinematic ways (with games like Alone and the Dark and Bioforge being influences), Grim Fandango truly changed the way the company's graphic adventures were presented. The tech allowed the game to embrace its movie influences with more opened arms than would have been the case otherwise, and for its time, the over one hundred hand 3D animations and extended pre-rendered cutscenes (with the still-relevant names Peter Tsaykel and Chris Schultz among the animation staff) were state of the art, and really only comparable to the work seen in a Pixar film.

As significant as these advancements were, the secret to the game's brilliance and impressive resilience comes from the way the technology is so effectively conjoined with the artistic intention. Most 3D games from 1998 don't stand up very well aesthetically, but the ways in which Grim is technically outdated aren't particularly bothersome. Take the low polygon count on the character models, which actually works in the game's favor on an art level given that the characters are intended to be reminiscent of crude paper dolls brought to life.

Furthermore, the pre-rendered 3D environments (based on concepts by the incomparable Peter Chan) are themselves examples of great, inspired artwork, whose beauty is no less than that of a 2D game, but simply of a different ilk. It is also Grim Fandango's most direct expression of its mythological influences. While keeping a pleasing consistency, the game covers an interesting range of styles from 1930s art deco (El Marrow), Aztec imagery (the gate to the Ninth Underworld), and even a bit of Picasso thrown in (a brief, eerie scene depicting the Land of the Living). As with its best forerunners, Grim Fandango is an example of great technical prowess but with even greater creativity and art direction to back it up.

And it's from a creative and artistic standpoint where Grim Fandango truly excels. A great world is nothing but wasted potential without great characters to occupy it, and this is a game filled with nothing but great characters. There are many who hail Grim Fandango as one of the best examples of writing ever in a video game, and you can add me to their number. The dialog in this game (apparently written entirely by Schafer, as the story goes, in a series of procrastination-induced binge sessions) is reminiscent of the tough talk of the crime film genre being celebrated, but is also just strong, funny, well-written, Schaferesque dialog. While we can't be that far off from a world where grand slams in this area are not such a revelation, this is the kind of dialog that can be seen as too good to be originating from a mere, psha, video game.

But it's not just well-written in having a sense of comedic timing or a plethora of witty one liners and clever barbs. It is well-written, with an incredible story and characters and arcs that you actually give a flip about. There are genuinely moving moments in Grim Fandango. While Spielberg waits for the world to "cry at level 17," engrossed gamers were already doing that at Chepito's lamp-guided departure from the Eight Underworld, or the final farewell at the game's climax. The characters undergo actual journeys, and the game is interested in keeping abreast of them. Attention to detail is paid, and nothing that gets introduced in the first act fails to be effectively paid off later on. You're invested in this story's outcome not just because of the time you'll spend with it, but because you're given real reason to be. Video games remain a young medium, and there are people out there who wrongheadedly wonder when it will get its Citizen Kane as if classics arrive with a classic status. All I can say is that, like Kane, the appreciation that Grim Fandango deserves continues to slowly be garnered over time.