Articles

Insecticide: What the Hell Happened There? Interview with Mike Levine and Larry Ahern

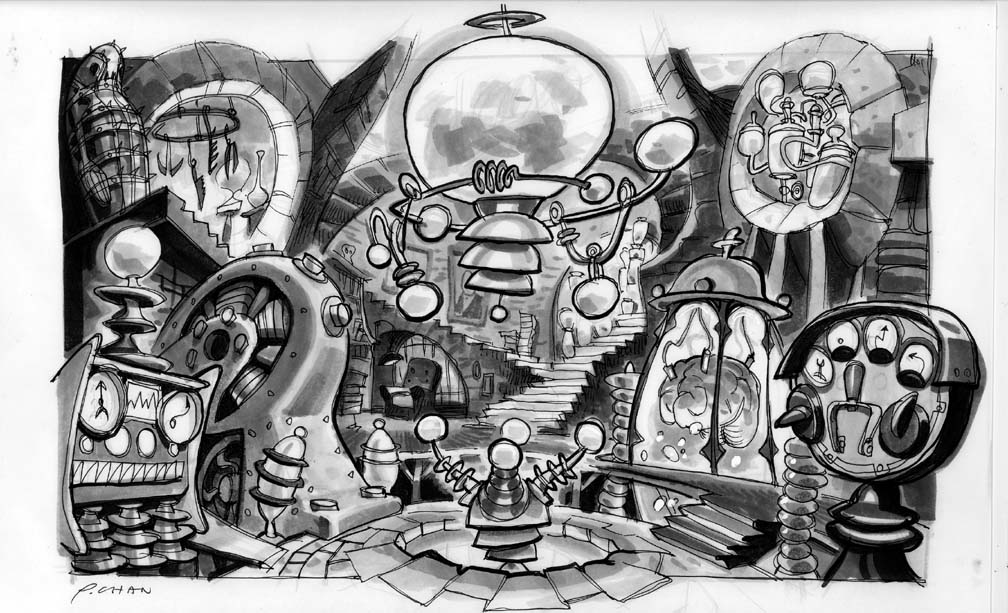

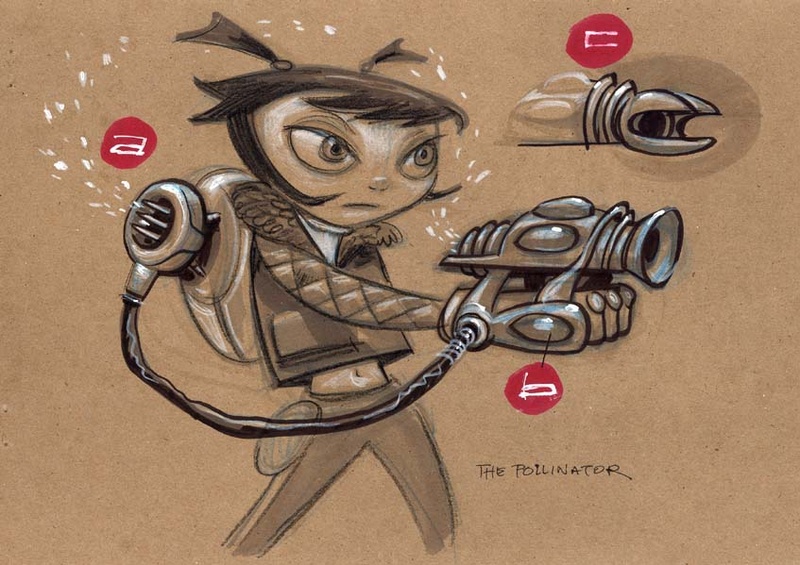

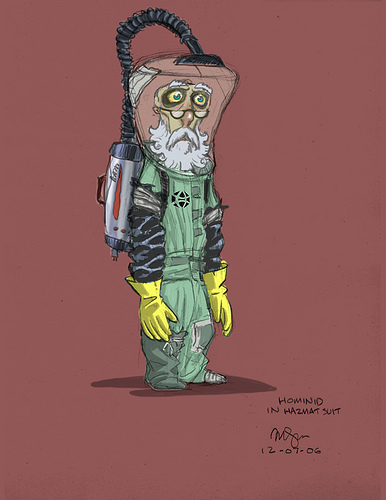

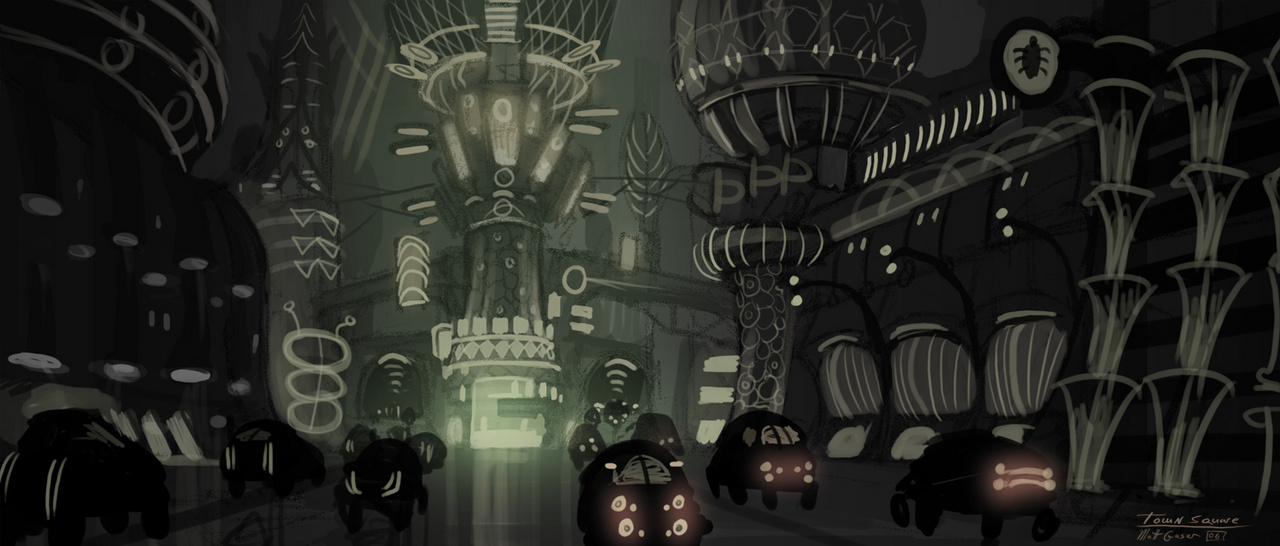

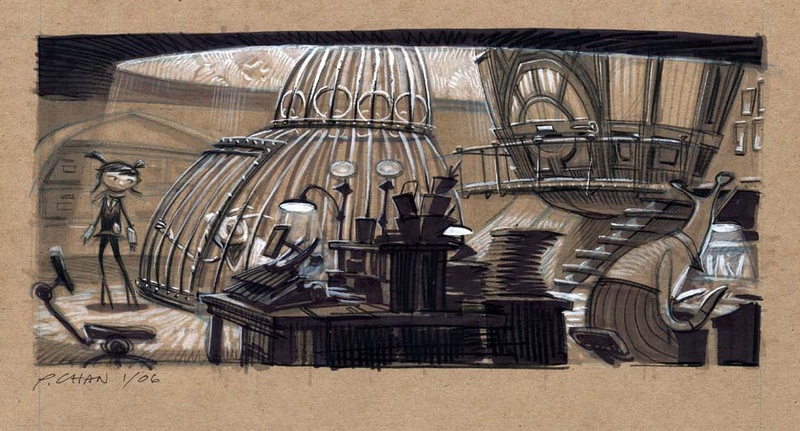

ML: I left LucasArts in late ‘97 after Dark Forces 2: Jedi Knight was wrapping up. Larry left years later. I formed a start up with people from ILM, then eventually moved back to the east coast, near where I grew up. I eventually formed Pileated Pictures, which did animation, then Flash and App development for toy companies and other clients. I then formed HappyGiant, which publishes our own games, and has been laser focused on Augmented Reality the last 5 years (see our partnership with Phil Tippett). I still live out here in Western Massachusetts. One of the reasons I moved out here was to fly fish, which I love. And it was really one day on the river, thinking about insects and their life cycles, that the kernel of the idea for Insecticide was born. I believe I kind of pitched a rough idea of it to Larry, and Dave Grossman, who was also very key in those early days helping us develop it. He really brought in the Gumshoe Detective vibe to it. It all just kind of came together nicely with all of us contributing. Peter Chan also did early concept work for us, and he really also helped set the tone and style.

ML: Oops, I think I just answered that! (: But let me use this space to say … Insecticide is a story anyone who has made, or is thinking of making an indie game, should read. It’s a cautionary tale, of the dark side of the gaming industry, when making your own original IP with publishers money. So … read on at your own peril. This is a story that started with hopes and dreams, and is now stuck in a dark place, where our arms and legs our bound, and we are incapable of moving. Sound fun?! Read on!

LA: I think the idea for Insecticide came as much from boredom as anything else. I seem to remember Mike was doing a lot of service work then and wanted to branch out and do more original stuff. And after several stalled games, I’d pretty much given up on Microsoft as an environment where I was going to be doing anything inspiring. Then Mike pitched his ‘insect girl’ idea, and it felt like an opportunity to build a crazy, fun fantasy world like the ones we’d worked on at LucasArts (and which seemed in short supply at the time). And once that fire was lit, I dove in with a level of enthusiasm I hadn’t had in years. The work just started flowing, and we began trading emails and phone calls, fleshing out the story, characters, and world. The whole process made me realize that I couldn’t be faking my way through art directing generic XBox games, I needed to be doing this kind of original work. Who cares that the market only wanted 3D shooters about space marines! We had a bug girl game that nobody asked for, America!

ML: Wow, I almost forgot that but you are totally right. I had seen The Professional around this time and really loved the relationship with the guy and the kid. We started with Chrys younger actually, but we aged her up as we went on as it didn’t feel right to have a 5-6 year old detective! Other influences … Larry?

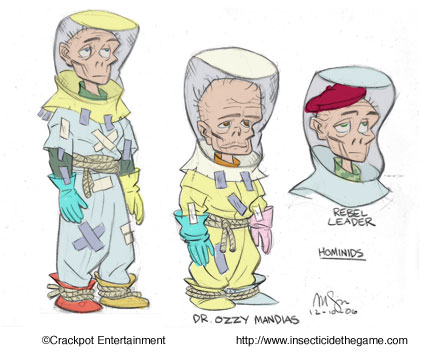

LA: Exactly! Talking bugs were completely believable, but 5 year old detectives just seemed to cross some kind of line. It’s hard to explain, but it’s cartoon logic. We talked about The Professional for the Roachy/Chrys relationship, then Raymond Chandler detective films for the hardboiled crime parts and the narration. Then there’s probably some Planet of the Apes and Wizard of Oz in there and who knows what else. The best original work is always at least partially stolen--I think the French call it ‘homage.’

ML: It took a long time. You have to remember, this was before the term “Indie” even existed in games. No one wanted to make an adventure game like this. Gamecock, our publisher, actually insisted we added in the action elements to the game. Given the climate, we caved to that to get the deal. This was also at a low point for adventure games. Double Fine wasn’t doing them. This was before Telltale. We were having some talks about turning it into a TV show, but when Mike Wilson showed up and was so pumped to make it into a game, and he made us an offer first, and we were really games people in our hearts and more comfortable with that, we decided to move ahead with it as a game. Albeit being nervous about the Action parts, and forced to work with another company for the programming side. Also remember, this was before Unity’s rise to prominence. Game engines were hard to come by and work with. We were just starting out and did not have an internal engine. So we had to work with an outside company, and that inevitably meant a loss of control on some level for us, of the final product.

LA: Yes, it was a long, slow road to lack of success. But, honestly, we didn’t care. If we had a good p.r. person to spin this, they might even say we were groundbreaking, bringing action-adventure hybrid digitally downloaded story-based indie games to the world long before Unity or Steam made titles like Insecticide viable. Or maybe we were just foolish. But between the initial interest we got from Hollywood for the cartoon pitch, and Gamecock’s excitement about the possibilities, we figured it was worth a shot. And, honestly, it was the game we wanted to make, so that was the most important thing.

In addition to being the project leads, you guys were running the company. Was this a difficult adjustment?

ML: That was mainly me and not a huge one, as I was also running my service based company prior to this, Pileated Pictures. The hard part of Insecticide is we made the decision to work with an outside dev house for programming, and that did take a lot of managing and time.

LA: I was mostly focused on creative direction. That, and another side project I had to take on when our budget got cut way back. But by that point, we were committed to making the project work any way possible. In order to bring in the talent we needed for the game, we set Insecticide up as a virtual production. Mike had worked that way on service projects, and we knew the approach would give us access to people we couldn’t otherwise afford, or who wouldn’t be interested in relocating. It meant being online or on the phone a good 12 hours a day sometimes (across multiple time zones from Seattle to St. Petersburg, Russia), but it was the only way we were able to pull it off.

You were able to get a number of fellow ex-LucasArts developers to contribute to the game – Peter Chan, Peter Tsaykel, Peter McConnell, Dave Grossman. Was it easy to reconnect with those old contacts?

ML: I was in touch and friends with all those guys, so it just kind of was natural. I don’t speak to all of them as much anymore, but several, I still do. I tend to be that way and keep in touch with friends … so it really was kind of a natural thing. “We’re making a game, we need music, let’s call Peter McConnell” Etc.

LA: I think a lot of the people you mentioned had the same reaction I did when Mike called: they loved the old LucasArts story games, and were always up for working on another similar project. Plus, being able to work with former teammates on something new was always fun. And, of course, for us the decision was easy; those people were and are among the best in the business.

How many internal developers did Crackpot have versus the outsourced talent?

ML: I mean, everyone was more or less full time on the project, when they were on it. The entire team was more or less put together for this project. Some of us had worked together at LucasArts, others were people one of us knew or somehow got connected to. All in all I would say the team was about 20 people or so.

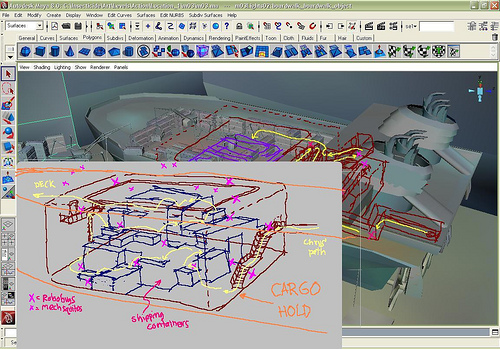

LA: We subbed some bigger chunks of work out to an animation company and a dev team in Russia, then Jake Stephens was our co-project lead and ran all level design. He and his wife, Brandi (our producer), were full time for most of the project, then various disciplines came in at different stages of the production and did their thing.

The detective levels, with their inventory puzzles and dialog trees, seemed well suited to a team with a background in LucasArts adventure games. Was designing the action levels more challenging?

ML: I think they were. When we approached Gamecock first about doing an adventure game, we were laughed at. Literally. So we kind of went back to the drawing board and we liked the idea of “action-adventure”, and so did they, so we ran with it. The action levels were more about Level Design, and keeping the action fun and interesting. But like Dark Forces 2 which I also worked on, we wanted to make you think a bit as well. That was our goal. So in the action, you still had goals and things you needed to accomplish.

LA: I think the hardest part came from having distributed teams when not all of us had a lot of experience designing action games (I’m looking at you, Larry). We had experienced level designers, we knew what we wanted for each of the level goals, and we knew the story points we wanted to hit, but I really needed the ability to bounce back and forth and adjust things as the levels were being built. As it was, we had to just try to set direction, then send it off to the Russian team to wire up. And at that point, we didn’t have enough of a budget to iterate much. We tuned a bit and fixed obvious problems, but we didn’t get much opportunity to polish the action levels.

Sierra veteran Josh Mandel was credited for writing much of the detective missions. What was the division of labor there?

ML: Yes, Josh and Larry did them from my memory. Josh was great and really helped us with a lot of the puzzle details.

LA: The irony was that designing and writing the adventure game detective missions was the thing I was most qualified to do, but by the time we were ready to work on that part, I just didn’t have the time. Luckily, we were connected with a lot of great talent, like Josh. He’d done similar work for King’s Quest and Phreddy Pharkas games at Sierra, and was also more than qualified to step in and do the work. I want to say that I had a rough design for the detective sections and handed it off to Josh to flesh out and do all the writing for, but I may just want to say that to take more credit than I’m due. Either way, Josh did fantastic work and we were lucky to get him.

The voice acting is terrific, which feels like another LucasArts holdover. Could you talk a little about that process?

ML: The hilarious and cool thing is, I still work with most of those actors to this day! They were great finds and we worked with a studio I had worked with previously in NYC. They do a lot of animated series and had a great talent pool. We had some great dialogue, and they really got into their roles and loved it.

LA: What’s great is that working remotely with voice talent is a pretty established process. Some of the other design work would have gone better with everyone in an office together, but the voice actors and engineers are used to handling things over the phone, and it’s all audio and not visual, which works well.

Insecticide was picked up by Gamecock Media Group, which was a brand-new publisher at the time. What was that relationship like?

ML: Well … where do I begin? At the beginning, it was great. And for most of the project, it went fine. But then, basically out of nowhere, they folded the company and sold off our game. We were told all would be fine, but we were never given the budget promised to finish Episode 2 for the PC, which is a shame as so much of it was done. All the cutscenes were done, and are now on Youtube in fact! Part 2 was over 50% done when they sold off the game and stopped paying us.

LA: It was frustrating how it ended. And the switch from PSP to DS really impacted the game we delivered, but since Gamecock was a new publisher, they were still setting up distribution and figuring things out, so there were a lot of unexpected changes. On the other hand, they were one of only a handful of publishers that even gave us the time of day, and they were very supportive of our creative vision. Just wish we’d been able to figure out how to find an audience for the game. Looking back, I realize it probably would have been a completely different story if we were able to put it out on Steam and find the audience that looks for that kind of game.

How did it come to pass that the Nintendo DS version came out first? Was that always the plan?

ML: No it was not always the plan. We planned to make a, gulp, PSP, and PC game first. But PSP sales were not doing well and DS were, so the pub convinced us to do the DS version. It was an issue as at least the PSP would have been an easier port from the PC. The DS required us to rethink everything. Luckily the programming house we worked with had an engine that could do 3D on the DS, so that is how we got it done.

LA: It was the reality of the marketplace, but switching from PSP to DS was probably the reason that neither sku was as polished as it could have been. Other than characters and storyline, the game play and interface on the DS were completely different from the PC version. It took a lot more work to make versions of the game for two very different platforms.

What were some of the limitations of the Nintendo DS port?

ML: Everything to my recollection. Everything had to be radically reduced to play.

LA: The biggest issue was character limitations. I think we could only have 3 or 4 enemies on the screen at any one time, which was completely different than the PC version, and required us to rethink the levels quite a bit to make them work. We also had a lot of interface issues to figure out, and had to dream up ways to take advantage of the second touchscreen. Because the original design didn’t factor in the second screen, we couldn’t make it a core component of the DS version, and as a result, it felt a little tacked on. On the other hand, the DS was a really popular platform, and a lot of the people who played the game found it to be the definitive version (my kids included). But the poly count for characters was very low as well, and cutscenes had to go through a bit of compression.

After the Nintendo DS version came out, the reviews were polarized to the point where IGN ran an interview with you just to talk about the reaction. From my point of the view the issue with the game had less to do with the reviews and more that it flew under everybody’s radar. What was your perception?

ML: I must be blocking this out. Larry?

LA: I’ll be honest, I’m not remembering this either. I know the reviews were average, but I would say that the game was not average. It was full of really good elements that were dragged down to average by a handful of elements that didn’t get the same level of polish (ahem… the action levels). And the action levels weren’t bad, they just didn’t have anything about them that stood out. We were hoping that the unique mix of adventure and action elements together with a compelling world, characters, and story might be enough to make the game stand out. But apparently not. I’m still not sure if it was because it didn’t work overall, if the game never got the right kind of marketing, or if the audience just wasn’t interested in that kind of thing 10 years ago. But we’re still very proud of the work that went into the game.

ML: We always believed in the concept of episodic adventure games. And this was long before Telltale. We just thought breaking it up and releasing it in chunks, like episodes of a TV show, was the way to go for these types of narrative games.

LA: It felt like it made sense to do from a production standpoint (delivering smaller chunks of adventure with a cliffhanger ending).It would be easier and cheaper to make portions of a larger game and be able to sell episodes along the way to fund the ones still to come. It also made sense from a technical standpoint in that each download would be smaller (something that was a lot more critical 10 years ago). And we liked the idea of an ongoing season of work. Clearly, it was something that other developers were talking and thinking about then (like Telltale).

SouthPeak Games acquired Gamecock in 2008, and that seemed to doom the game’s future. Is that right? What exactly happened there?

ML: To this day, I am not even 100% sure what happened. All I know is fast forward to today. A company we do not even know is still selling Part 1 on Steam. We have not gotten a Royalty Report from them in about 5 years. We have tried to contact them numerous times, but they do not respond. SouthPeak seems to either no longer exist, or spun out into a web of smaller companies, making it impossible to trace or contact them. If you look at their Wikipedia page, their ending was pretty sketchy. And there were many companies unhappy with them after the sale. (Note from Jason: See more here.) A group even was created (not by us) and started a website called “SouthpeakJustice” but it went nowhere. All I know is someone is selling the game on Steam and has had no contact with us whatsoever. I have reached out to Mike Wilson for help, asking for very little in my opinion - just help getting it taken down off of Steam, but he has refused to help us.

LA: I’ll defer to Mike on the story here. I went off and started on other projects and am still confused on what happened. The world may never know.

How far along was the second half of the PC version when the funding disappeared? I know that you eventually were able to get the cutscenes uploaded to Youtube, but were there any avenues explored for getting Part 2 finished up without a publisher?

ML: I believe we built most of if not all the other levels, we just did not get them coded. We did explore speaking with Southpeak, who never returned our calls or emails about it. We also have spoken with Mike Wilson as I have said about also helping us, but he doesn’t seem interested.

LA: Yeah, it was all designed and figured out, cutscenes animated, most of the levels built and figured out. It just needed to be wired up. We had always thought of the PC version as the definitive one, so most of the work had been done. It’s a shame, since releasing the Part 2 cutscenes is something, but it doesn’t really deliver on finishing the story, since the levels in between the scenes have additional story elements. As a standalone, the Part 2 cutscenes don’t quite make narrative sense without additional notes to explain what happened in the gaps.

Had the release gone better, were there any addition platforms you had hoped to release Insecticide for? I remember it striking me as particular well-suited to the Wii, since that would have allowed both the point ‘n click elements of the DS version and direct control for movement.

ML: No plans per se, but I agree that might have been cool, albeit with some re-working.

It was mentioned that you guys attempted to shop Insecticide around as an animated series. Who did you talk to and what was the response?

ML: We actually got pretty far along with Nickelodeon. Cartoon Network also saw it, and liked it but not as much. Mainly, Kids Television is very “trendy” and back then, Insecticide was perceived as too dark. Now there is Adult Swim but they tend to like more outlandish things or scantily clad women, etc. Insecticide doesn’t fit into a “box”. Honestly, it would make a great Netflix series if anyone is listening.

ML: Aside from the basic things like having the time to pull that off, all the legal greyness of the IP made us a little worried. Mike always told us we own the IP, and that is what the contract says. Also having done one Kickstarter, they are incredibly hard to raise the funds needed to make a game like this, unless you are Tim Schafer that is.

Was there ever an intention to do more with Crackpot than Insecticide? Do you see any future for the label?

ML: I mean, never say never, right? Sure we had plans back then, but when Insecticide fizzled out, and we had moved on to other projects, and there was no real market for adventure games, it all petered out. These days I funnel most stuff through HappyGiant. We’d love to bring it back. We will see. And there are even some old LucasArts games we would love to bring back, but we will see about those.