Articles

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom 35th Anniversary Review “I understand its power now”

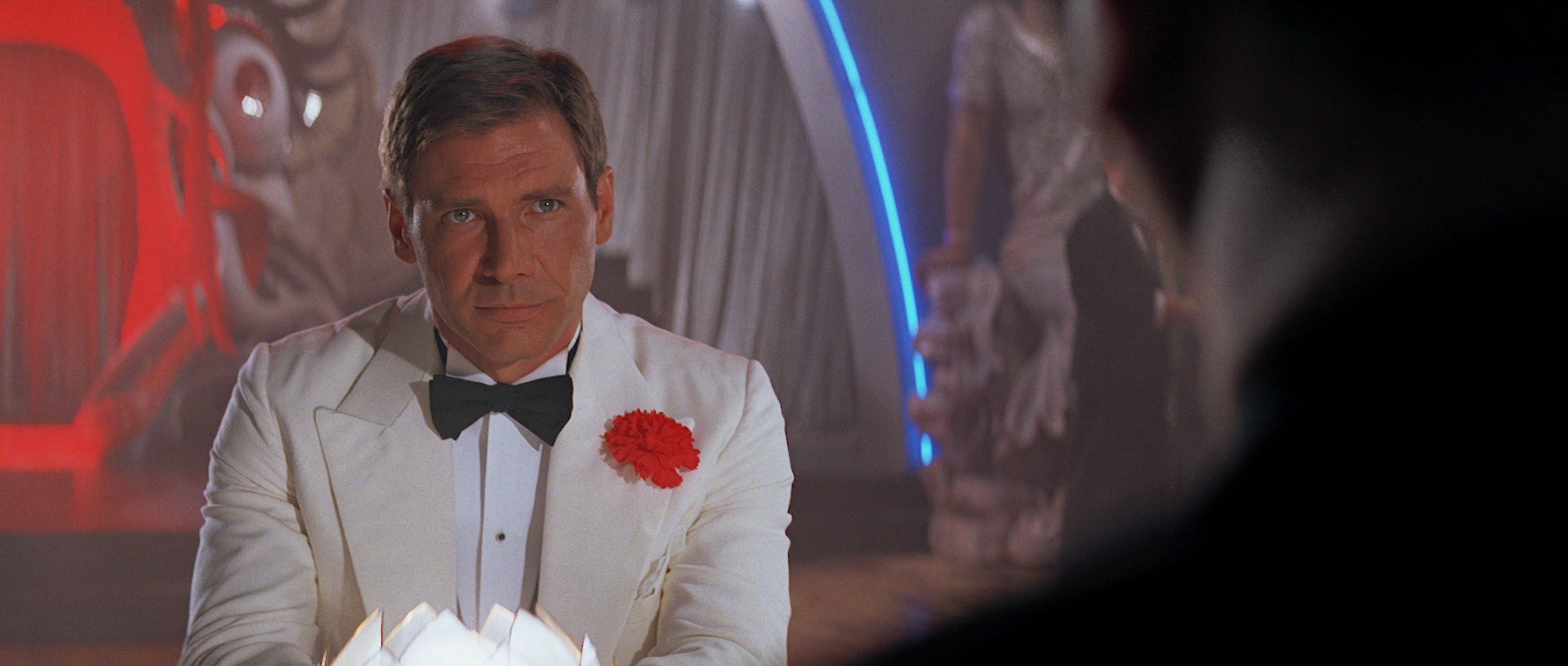

Indeed, Temple of Doom‘s merit as a sequel derives largely from its contentment not to compulsively remind you of Raiders nor to slavishly adhere to a template. It was produced early in the series’ history, when Spielberg and Lucas were still following their original conception of a quasi-James Bond model. The Indy films have been dutiful in acknowledging their debt to EON Productions’ spy serial, most explicitly when the third film cast the original Bond himself as Indy’s father. Temple is no slouch, though, with Indy making his entrance in the same white tuxedo Connery donned in Goldfinger.

For better or for worse, this early notion of the Indy films being standalone adventures, with the intrepid archaeologist himself the only reliable recurring element, was jettisoned when the third film transformed from “Indy 3” to a trilogy’s finale over the course of its development. But Temple was produced when the series was still seen as indefinite and wasn’t yet encumbering himself with the trappings of a saga, resulting in a totally refreshed supporting cast. Spielberg and Lucas have explained that one of the two reasons Temple was approached as prequel was the ease with which it allowed them to swap the “Indy Girl” without having to explain Marion’s absence.

The second justification for setting Temple before Raiders, however, is the more interesting: It presented the opportunity to give Indy a journey wherein he transforms from abject graverobber to the (slightly) less morally gray character we meet in Raiders. Reputedly, an early concept for Temple saw the reprisal Paul Freeman’s Belloq, depicting a time when he and Indy were still collaborators. Presumably, we would have witnessed the fracturing of their relationship when it comes upon a line Indy will not cross. The basic idea of Indy tuning his moral compass survives the finished film, when the plight of the enslaved children overwhelms Jones's initial, purely avaricious motivation to attain “fortune and glory.” Given the circumstances, it’s a fairly well-executed arc for the character, and for a movie that is typically accused of being pure sound and fury, eschewing substance of any kind.

For all the “faults” found in Temple that I contend to be misdiagnosed, it’s nevertheless true that the movie can be tonally bizarre – some have said schizophrenic. This effect largely comes from the broad humor the movie lards its fundamentally grim storyline with. (The mallet falling on a bystander’s head might have come from The Three Stooges' sound library.) While I’ve no doubt that some of these moments represent a desperate attempt by Spielberg to leaven things anywhere he thinks he can cram a laugh, I don’t think the liberal injection of farce amidst high stakes is much of a deviation from the 1930s genre attitudes to which the film is paying tribute.

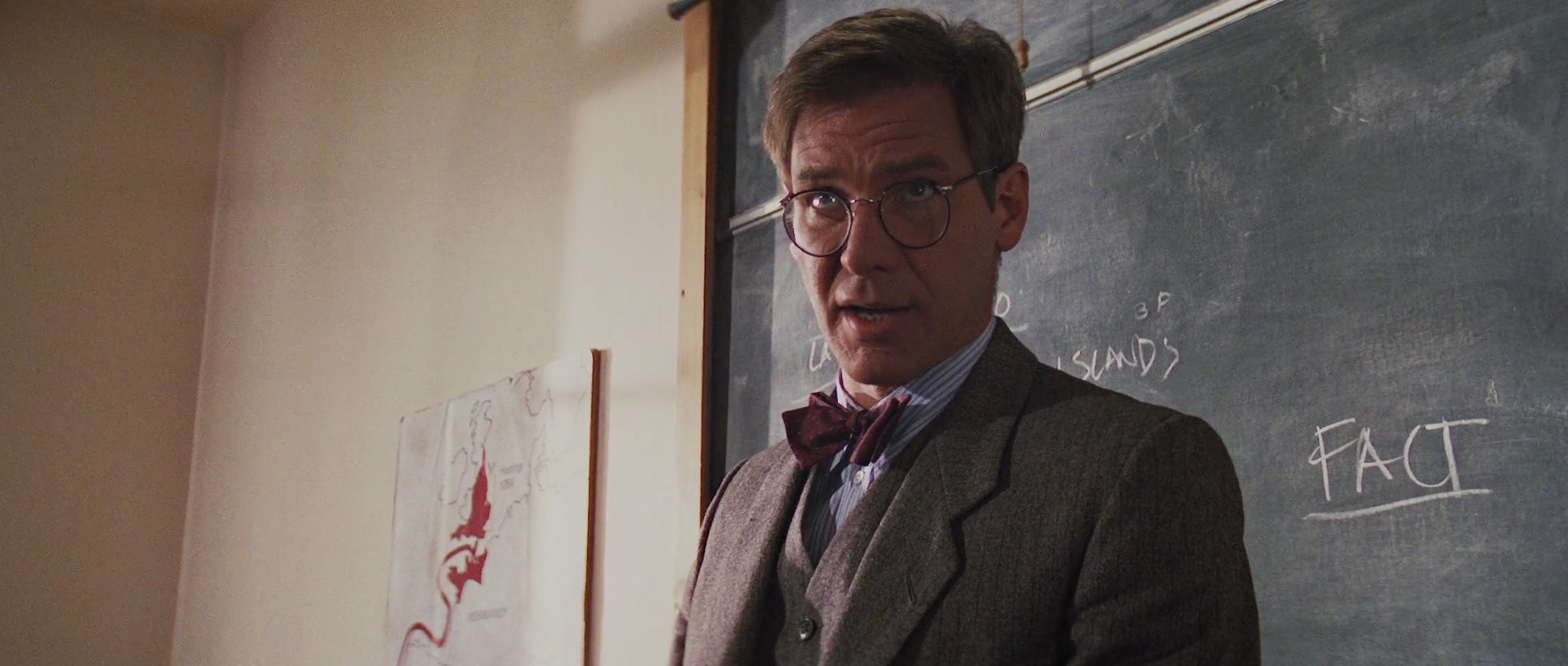

Nor is it exclusively without method. The much-maligned, gross-out banquet scene is a juvenile hoot, but it’s also a tactic to spare us from the slog of undistracted exposition; Willie and Shorty’s vaudevillian introduction to outrageously fictional exotic cuisine is crosscut with an extended information dump between Indy, Chatter Lal and Major Blumburtt. The scene is also an interesting one for the way it demonstrates how this sequel honors its predecessor without aping it. Temple, which discards the post-teaser college sequence that the subsequent sequels retroactively made an obligatory routine, basically makes the palace dinner the equivalent of the “Professor Indy” segment, not just because of its functionary purpose but because it’s the one scene where we see the character gussied up and bespectacled as we find him in the other films’ classroom scenes.

All my gushing and counteroffensives are not to say that there isn’t some indefensibly stupid stuff in the movie – Short Round kung fu-ing Thuggees is garbage – but I can cite those examples on one hand, and I never see them represented when people are listing out the things that are oh so wrong with the movie, which inevitably look like its greatest virtues on my end. With Indiana Jones, Spielberg and Lucas created a sandbox where too much is a boundary unlikely to be found.

Temple is great even when it’s dumb, because it’s coasting on such an infectious sense of mischief that, well, anything goes. Moments like the completely incongruous Ben Burtt punch sound when Willie slaps Indy or the Scooby Doo escape of Mola Ram through the secret floor panel put a smile to my face just thinking about them. Far from being elements I must look past to enjoy Temple of Doom, the goofiness and eccentricities are a fundamental part of the mirthful lunacy that keeps me coming back to it. I can think of few movies that come across as thrilled as this one is at getting to be a movie.

Just as Temple’s darkness does not overwhelm its inherent joyousness, its inability to sit still, particularly in its second hour, manages not to wear thin. Temple is exhausting, yes, but its high RPM isn’t to the incomprehensible effect of too many modern action films - Spielberg is simply too talented a compositionist to fall into that trap. Still, it’s a movie that you survive more than watch. When the protagonists finally emerge from the mines and see daylight again, we feel somehow as though we’ve been through the ringer along with them. Engagement under duress is engagement nevertheless. Following the rope bridge climax, an Indy battered within an inch of his life slowly climbs up into view, revealing not only his improbable survival but that he has recovered the McGuffin intact. We feel much as Willie and Shorty do when they burst with relieved laughter. Do we feel anything when the heroes emerge from the Mayan temple after the climax of Crystal Skull, spouting lame platitudes while posing in perfunctory disarray against digital background plates? One sustains more lasting physical damage than the characters in that movie do over a standard round of air hockey.

So yes, I love Temple of Doom. I love it as unabashedly as it seems to love its medium, which it treats as a privilege and a thrill to operate in, an opportunity it cannot fathom celebrating with a pitch anything less than full-throated. This is a hungry, hyperactive movie that behaves as though its makers were certain no one would ever give them access to a camera again; it has the gusto of a heist it cannot believe it’s getting away with. It is the balls-to-the-wall adventure movie, an escapist yardstick whose stubborn grip and enviable momentum are a reference point that never has been equaled. I feel sorry for its imitators, just as I feel sorry for Steven Spielberg. Imagine being someone who can’t enjoy Temple of Doom.

A review by Jason, who does not condone the punching of night club waitresses unless it's really funny.

SOURCES:

- Movie Screencaps.com - Source of Blu-ray screenshots from the Indiana Jones films.

- Pinterest - Source of image from Goldfinger.

- Goomba Stomp - Source of image from The Treasure of the Sierra Madre.

- The Great Silence - Source of image from Gunga Din.

- Indiana Jones Wiki - Source of production still of Dan Akroyd during the filming of Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

- Youtube embeds sourced from public channels.