Or: How the post-Gilbert Monkey Island games understood the infamous subtext better than you think

It’s common knowledge that creator Ron Gilbert refers to the Pirates of the Caribbean theme park ride at Disneyland as an influence on Monkey Island.

That background makes perfect sense. It’s also incomplete. The story of the ride – at least in its original form - doesn’t have much in the way of overt supernatural elements. And so a major piece fell into place when Gilbert began acknowledging On Stranger Tides, the 1987 fantasy novel by Tim Powers, as a supplemental influence, thus explaining why Monkey Island isn’t merely a pirate adventure, but a ghost pirate adventure, back before the blend was an obvious one. So while there’s a fair bit of Disney there, the voodoo and the ectoplasmic villains are bits of texture that likely originate from Powers.

I’d further argue that The Secret of Monkey Island has a rather discernible The Princess Bride (the movie) thing going on. Speaking from experience, once you see the first game as the marriage between Tim Powers’ novel and Rob Reiner’s film – also a 1987 release - you pretty much can’t un-see it.

But the Pirates of the Caribbean connection is what gets remembered. There’s clearly more than a surface-level extent to the comparison, and there’s a reason it continues to be the influence that endures when people describe the series in capsule form. I think this quote from Gilbert at the time of Monkey Island 1’s release gets to the heart of the relationship:

I'd wanted to do a pirate game for a long time. You see, one of my favorite rides in Disneyland is Pirates of the Caribbean. You get on a little boat and it takes you through a pirate adventure, climaxing in a cannon fight between two big pirate ships. Your boat keeps you moving through the adventure, but I've always wished I could get off and wander around, learn more about the characters, and find a way onto those pirate ships.

So with The Secret of Monkey Island(TM) I wanted to create a game that had the same flavor, but where you could step off the boat and enter that whole storybook world.

You might say that Monkey Island is the wish fulfillment of a kid who wants to explore the universe of a theme park ride. I’m treading no new ground here - the insight has fed into a widely recognized theme park subtext that runs throughout the series as a whole. Some take the extreme interpretation, which could very well have been close to the original intention – namely, that Guybrush’s adventures are the daydreams of a boy lost inside a theme park.

The climax of Monkey Island 2 all but goes there explicitly before punting with an end credits stinger that gave future custodians of the series an out. Convenient epilogue curses notwithstanding, all agree that there is at the very least a firm handshake between the world of Monkey Island and Disneyland.

It’s been a crucial angle in the fan attempt to divine the meaning of Monkey Island 2’s surreal ending (as suggested above, I think it’s a long solved riddle) as well as surmise what Gilbert may have had in mind for the third Monkey Island game, if indeed he’d opted to close out his supposed trilogy before leaving LucasArts. Much has been written, replete with some really convincing visual aids, on the subject already, and I don’t want to retread well-worn paths.

What I do want to address is an unfortunate bonus objective of these theories, which is as a cudgel with which to beat on the subsequent sequels, three great games which the most closed-minded fans instinctively dismiss on the trumped-up charge that they violate a canon only Ron himself can truly preside over.

But who’s to say they violate the canon? That theme park connection suggested by the first two Monkey Island games has never been forsaken. Far from it, in fact.

The easiest evidence to point to is the anachronism humor, which has prevailed as a staple of the series. While The Curse of Monkey Island retcons the theme park Guybrush found himself inside at the end of the second game into “The Carnival of the Damned” located on Monkey Island itself, this rewrite only comes with a whole new slew of theme park allusions.

Employing its own post-credits stinger, Monkey Island 3 dives head first without a helmet into the Disneyland homologue, aware enough to punch out on a winking reference to a popular urban legend about Walt Disney being buried in a deep freeze beneath the Pirates ride. It’s undeniable that the guys behind Curse recognized and understood what was going on with this series beneath the hood. In fact, by virtue of the fact that it has survived every installment, we can conclude that this element has been viewed by every team as inalienable from the series.

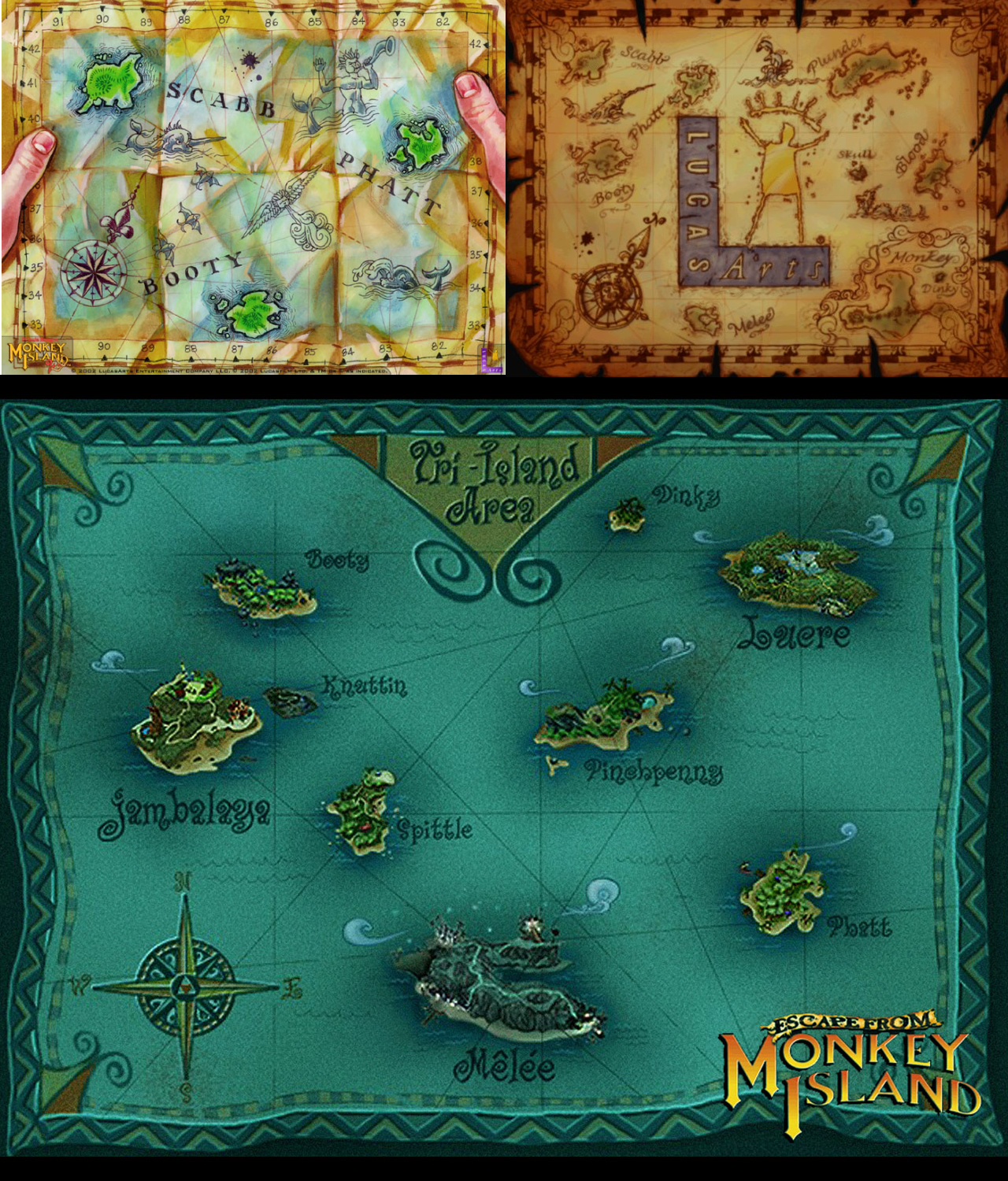

Which is not to say that it’s an easy element to wield. It is a balancing act and a sensitive one, and I’ve long suspected that botching it is the reason so many give Escape from Monkey Island, which converts the Caribbean into an epicenter of corporate tourism – hell, it all but depicts Jambalaya Island as Downtown Disney - such a hard time. By yanking the subtext way up into the text, the game flies too close to that particular sun.

Starting with a clean slate and setting its story outside of the “Tri-Island Area” – a retrospectively envisioned domain of islands that was getting more claustrophic with every outing - Tales of Monkey Island course-corrected a bit by dialing back the self-awareness immensely but not entirely, acknowledging it as a key part of the saga’s identity while telling a story that felt more authentically pirate-y.

The Disneyland nods prevailed: Flotsam Island’s Club 41 is a reference not just to an all too easily exceedable WiiWare megabyte ceiling, but to an “officially secret” Disneyland night club. And, in one of the series’ most significant yet overlooked touches, the depiction of the Pirate Crossroads reprises a pointed visual cue.

The games behind LeChuck’s Revenge are certainly not what Ron would have made had he not voluntarily left LucasArts in 1992, but I think something that becomes more clear as the series ages and can be more easily evaluated as a whole is that the hands he left the series were more than capable – they “got it.” I contend that all five teams – at the end of the day a fairly compact group of San Francisco developers with loads of overlap – treated the universe not just with reverence, but with an understanding that they aren’t commonly credited for.

I remain unconvinced that he could or should, but Ron has already stated that if he ever were to make “Monkey Island 3a,” he would split the canon and simply continue the series where he left it off, but I wonder if he would necessarily have to. I mean really, what’s changed? It seems to me that the subsequent sequels have been keeping the bench warm, faithfully keeping that barrier between fantasy and reality blurred. That portal remains open, and that carnival remains a daydream’s interruption away.