Articles

Maniac Mansion and the Orphaned Tone Page Two

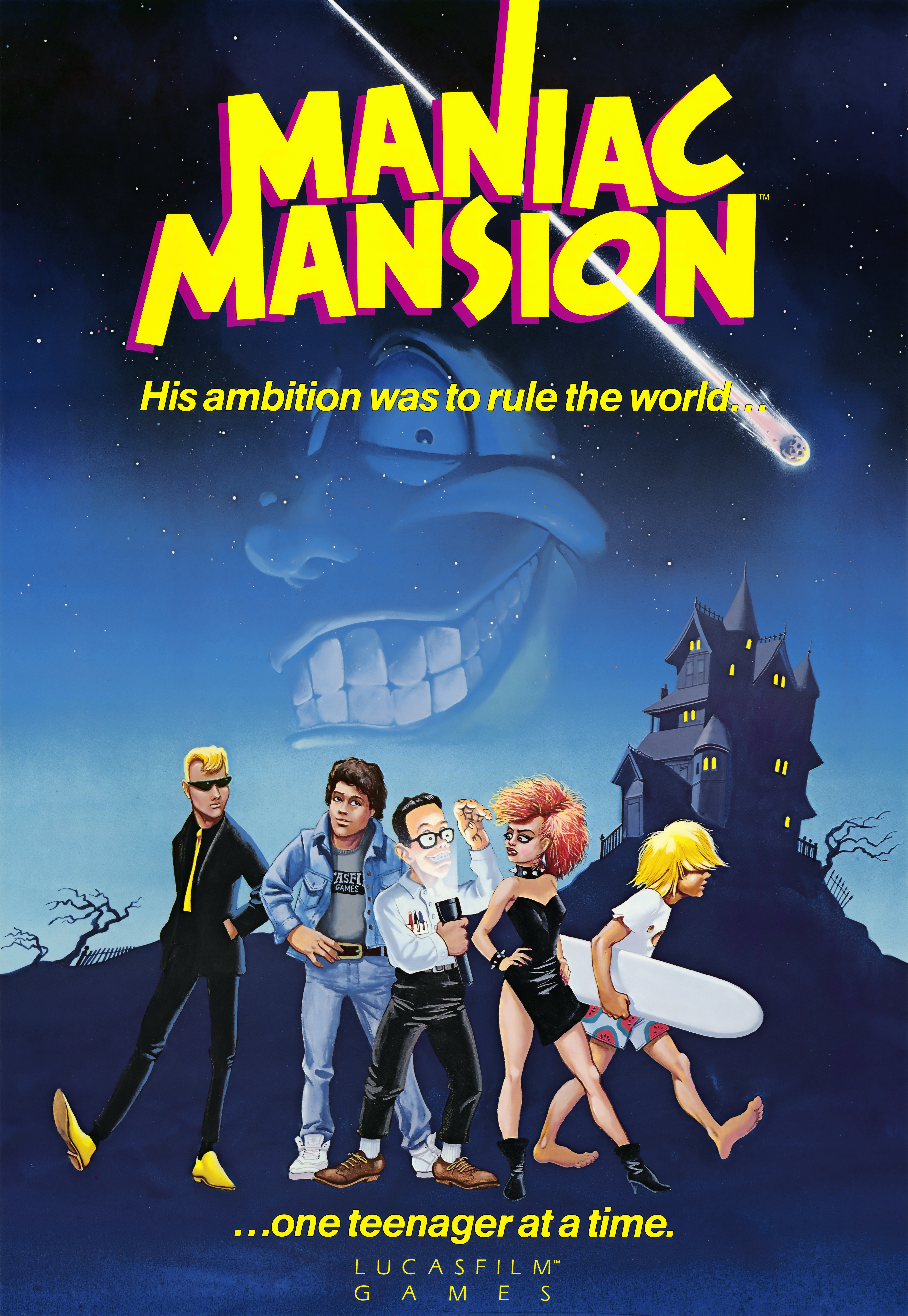

With old video games, all that misleading concept and promotional art is often the only sense we have of how the game’s characters and world might have been expressed unadulterated instead of within the confines of, say, an 8-bit cartridge. I still find the manuals of old Nintendo games to be great fun to look back on because of the illustrations they were often littered with. The impressions they made had a way of seeping into your imagination and becoming what your mind’s eye saw while your real eyes were staring at the gauzy pane of a tube television.

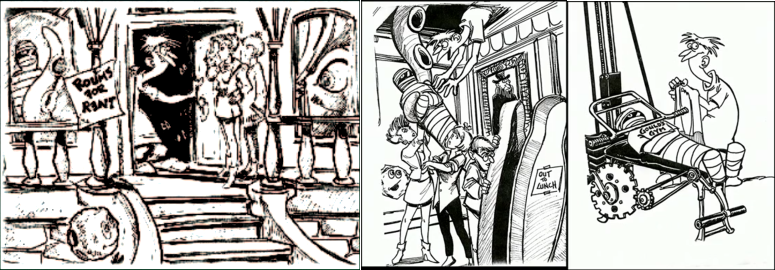

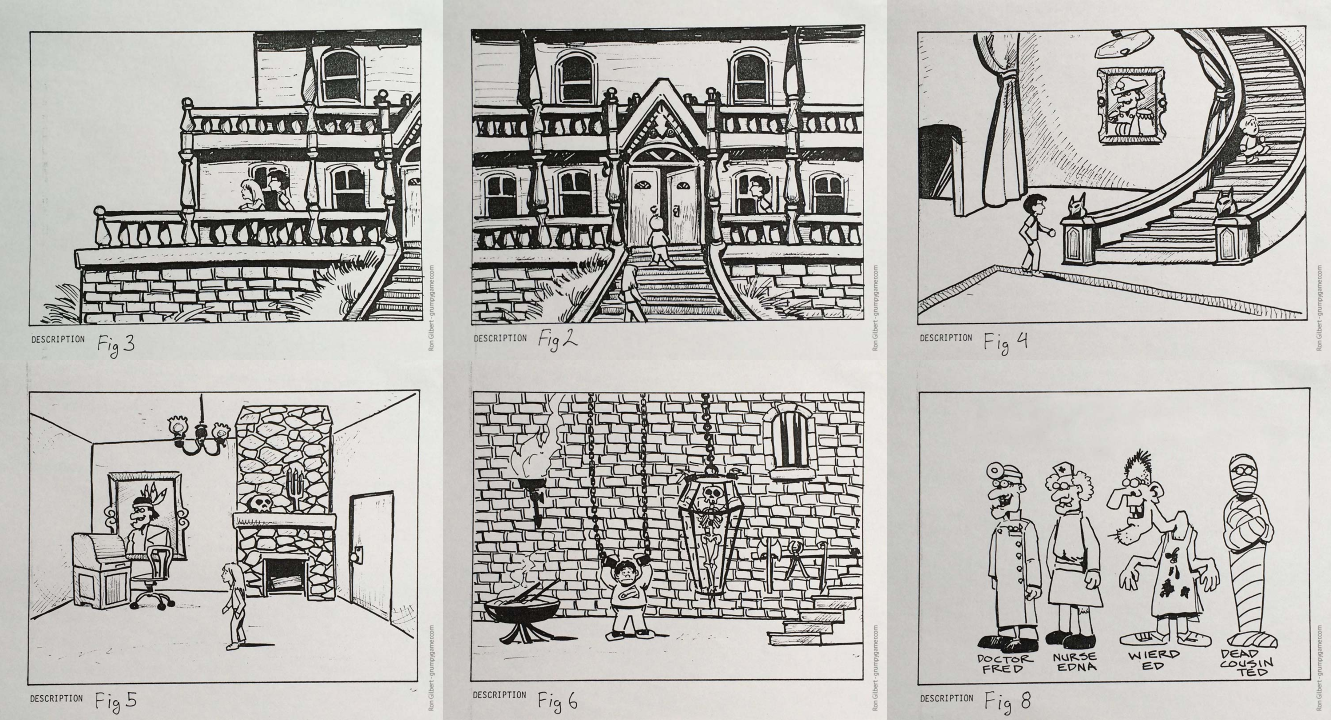

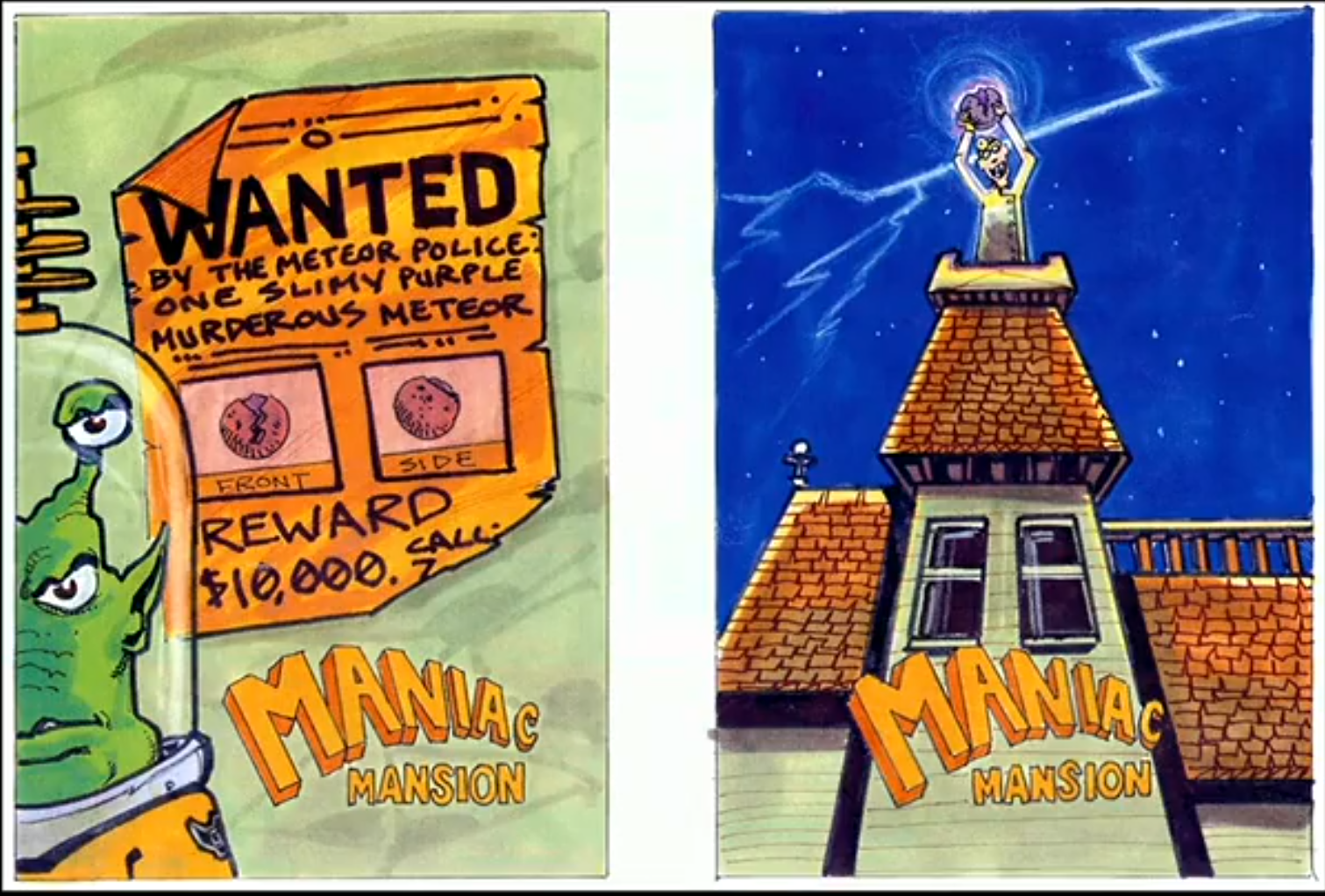

In the case of Maniac Mansion, we have several samples of Gary Winnick’s concept art which give us an idea of how he and Gilbert saw their own game’s style before it had to surrender itself to the Commodore 64’s memory cache. It’s worth noting when browsing these images that the process of developing this game was a uniquely free and fluid one: Gilbert was permitted by an exceptionally de-regulated studio culture to let his conception gestate long before he even knew what genre the game would be made in, and Winnick’s concept art in a way can be seen as part of the two leads’ attempt to find the identity of the project themselves. It’s hard to imagine a development process that amorphous and unhurried to be possible even a few years later, or at another studio, and certainly not in the modern era.

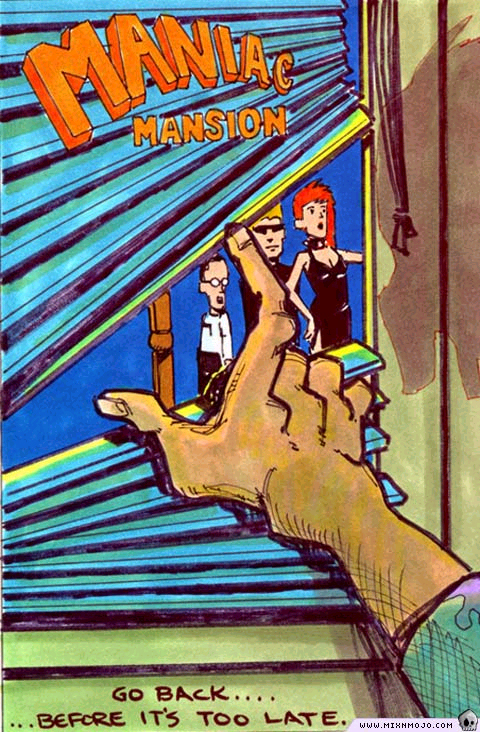

As telling as Winnick’s concepts are, the work of outside artists in expressing the world of Maniac Mansion gives the deliberateness of Day of the Tentacle’s swerve an even finer clarity. At the very least, what Peter Chan and Larry Ahern (the driving forces of Tentacle’s art team) extrapolated from the predecessor was a rather distinct conclusion from the one other interpreters arrived at, and which seem to share a common denominator. However much creative license was taken when the task of capturing the first game’s personality was left entirely to the imagination of an artist who could work with ink and paint rather than a scant few pixels, it’s noteworthy how much closer their results feel to the spirit of the inspiration compared to the bright, welcoming vision of the slapstick sequel.

Perhaps the most stunning piece of Maniac Mansion themed artwork comes courtesy of LucasArts legend Steve Purcell. The creator of the Sam & Max comics was not on the team of the original game, but was commissioned to do an Edison family portrait to be used as part of the rear packaging of Maniac Mansion’s “enhanced” edition in 1989. I was extolling the virtues of this oil painting just recently, but anything worth doing is worth doing twice.

On his blog, Purcell notes that Walt Disney’s Haunted Mansion ride was a frame of reference for this piece, and that comes through clearly. While only so much insight can be gained by directly comparing this standalone, marketing-specific creation with the game itself, that connection to the sepulchral theme park attraction nevertheless feels like an astute and appropriate one for Purcell to draw, and the artwork rides that line between goofy and grotesque that to me sums Maniac Mansion right up. For as much as Purcell puts his own stamp on things, the painting evokes the essential spookiness that would be jettisoned by the zero-gravity, funhouse mayhem of the sequel.

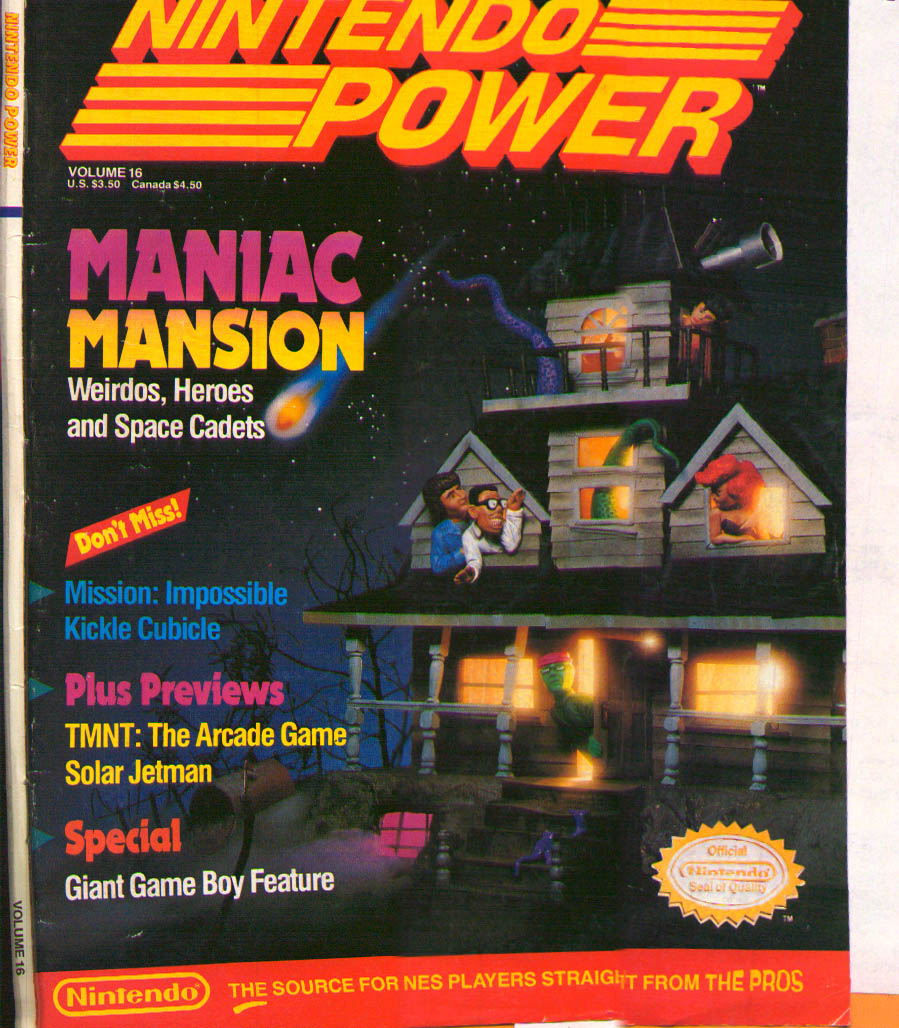

Some of the odder articles of Maniac Mansion ephemera seem to further the point that artistic license can be seized without straying unrecognizably far from the mothership. The September/October 1990 issue of Nintendo Power magazine features a cover story on Maniac Mansion, and the front page touts the new release in the form of an eccentric clay diorama of the mansion and the cast. (This playful approach to a subject was taken in a number of the early Nintendo Power covers, with probably the most recognizable example being Super Mario Bros. 2‘s treatment on the front of Issue #1.)

The Maniac Mansion diorama is another wonderful, weird example of a commissioned work from a third party that goes very much its own way while at the same time getting it really right. The tableau is simultaneously charming and off-kilter in a way that, again, feels true to Maniac Mansion. Moody yet fun, it summons some strange energy with its tactile, quasi-realistic approach -- I’m thinking particularly about the depiction of the tentacles, who are far less anthropomorphized than they appear in either game.

I’ve been so taken with this cover for so long that I made some (frustrated) inquiries in an effort to get in touch with the artist for a quote. (UPDATE: But check out these sweet photographs of the original work that survive.) Sufficed to say, I present their unsigned creation as an additional exhibit in the case that Maniac Mansion can be visually reinterpreted in such a way that retains the character of the game even while giving it one heck of a twirl. And I’ve no doubt many were inspired to add Maniac Mansion to their Nintendo library on the strength of that curiously enchanting craftwork.

Okay, we get it. Jason sees Day of the Tentacle as a radical departure in tone from Maniac Mansion. Why does that need this much attention? Well, it’s not to lament this departure, and to be clear, I consider the choices that Dave Grossman and Tim Schafer’s team made to be a perfectly valid take on the property as opposed to some misinterpretation. Opinions that carry actual weight agree: Gilbert and Winnick, who participated in the sequel’s early brainstorming sessions, had nothing but praise for the direction the game took the series. As much shapeshifting as I contend Day of the Tentacle did, it’s still Maniac Mansion. As Grossman reflected on the matter of its faithfulness to the original, “I think DOTT still resembles it a lot more than that TV show did,” and he’s certainly right on that count.

My complaint, really, is the fact that the shapeshifting stopped with Tentacle, even after it brazenly nuked the hamster (so to speak) and proved that the series could not only survive reinventing itself, but excel at it. When you consider how successfully the game pulled off its extreme makeover, the possibilities of where this series could go from there seem close to endless. What Day of the Tentacle demonstrated is that this may be the most malleable of the LucasArts adventure properties, and yet it stands among the most neglected. The second game in the series is still the latest, and it carries a 1993 copyright date. The series is unconsummated innuendo -- as cruel a tease as handing somebody a pilot’s license before permanently grounding all flights.

It was regrettable when Maniac Mansion wasn’t invited to join in on the LucasArts revivals that Telltale was briefly dabbling in before The Walking Dead overwhelmed that agenda, and it doesn’t feel like we’ve ever come closer to a continuation since. The potential of this series as an aggressively adaptable love letter to “B-movie themes” (which is about as much of an organizing principle as I can land on for Maniac Mansion, and which can obviously be abstracted in countless directions) is still waiting to be played out.

The only other manifestation we’ve had of the Maniac Mansion universe came in crossover form with a Day of the Tentacle-themed bonus level in Zombies Ate My Neighbors, which was in production at the same time. Visually, Zombies proved a compatible fit with Day of the Tentacle, while its relative violence, its teenaged protagonists and the alien invasion element of its story recall Maniac Mansion. Perhaps the tonality of Zombies can be seen as kind of a missing link between the two.

It’s been pretty slim pickings for the Maniac Mansion faithful, all in all. And so until Disney is ready to finance Dr. Fred’s next crime against nature instead of Jared Leto’s*, all we can really do is vainly ponder where the series could go from here, and there isn’t much that’s off the table. I mean, Day of the Tentacle literally reforms murderers into plush-ready sidekicks who carry an alarming attraction in the cos-playing community.

If that doesn’t convince you that the possibilities are boundless, do us a favor and stay out of the design meetings for Maniac Mansion 3. This is a brand too important to me, to be left to the sane.

Jason

*I don’t actually have any strong feelings about the Leto-led Tron 3 that’s been announced. I just wanted to work that joke in.