Articles

Maniac Mansion: The Liner Notes Developing the NES version

Jason pays tribute to his gateway to the LucasArts adventure catalog and shines a light on the musicians behind its standout soundtrack.

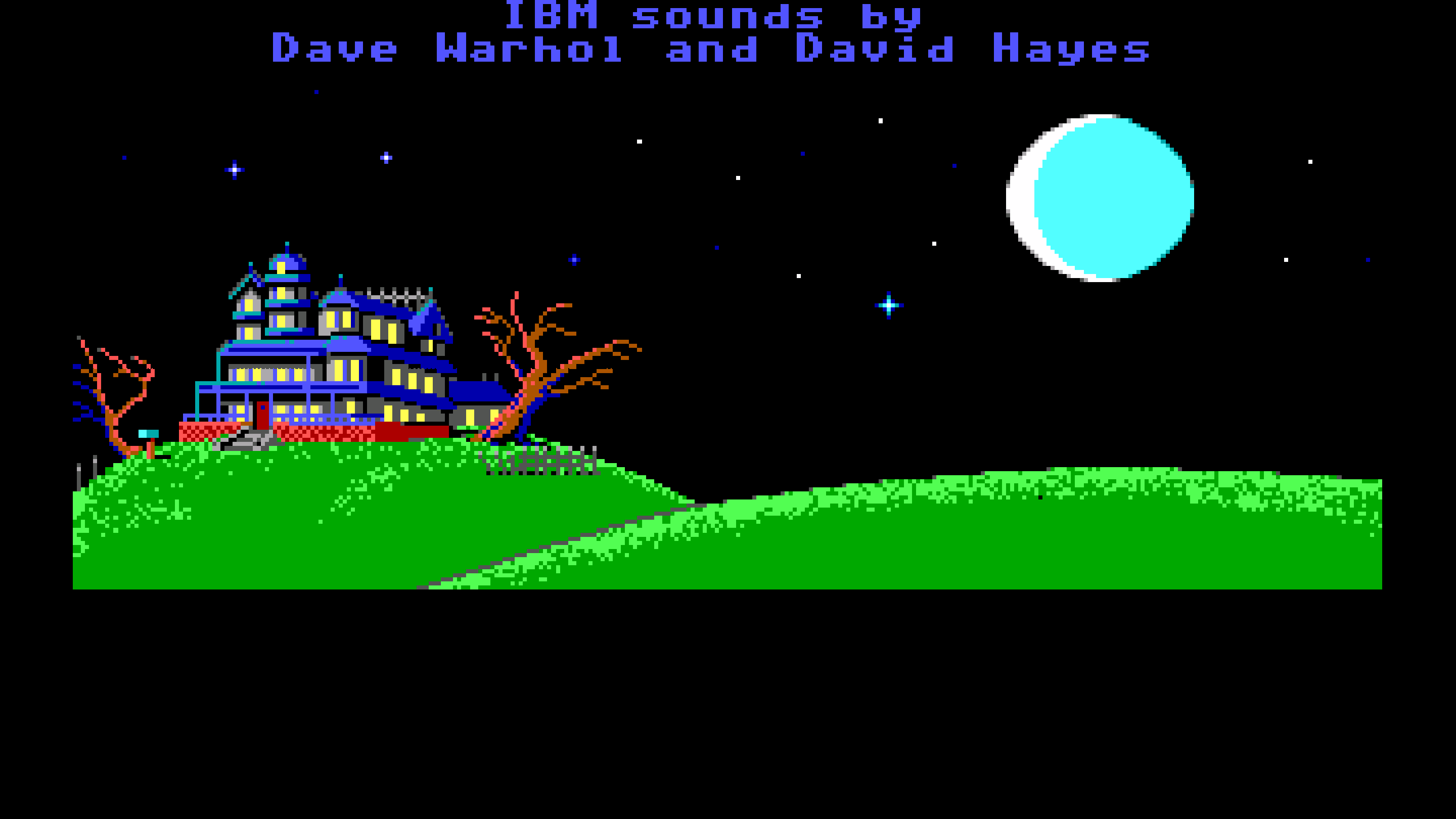

The Nintendo version of Maniac Mansion is exceptional among just about any console adaptation of a computer game that I can think of. The censorship woes it endured make for a good story, but it really doesn’t need the added intrigue of controversy to be memorable; it stands on its own two feet as a particularly high-quality port.

When the cartridge was released in September 1990, it introduced a whole swarm of unsuspecting players to the concept of the story-based video game, myself included. Jennifer relates: "I managed to talk to Ron and Gary at PAX East when I was working at the Double Fine booth, and Ron said that most people tell him that the NES was the system they used when playing Maniac Mansion." The persistent fondness for this version suggests qualities that supersede nostalgia or any status as a curio. It is, in short, something special. I like to assume the best of Limited Run Games, so maybe their choice to neglect the 30th anniversary of LucasArts' first (and best) Nintendo cartridge and conduct a loving reprint of this instead was a clerical error or something.

An easy way of highlighting the release's caliber is to compare it to a lesser-known and truly strange counterpart for the Famicom Disk System (the Japanese equivalent of the NES), which was released a few years earlier. Although both versions share the same publisher, Jaleco, and the content of games released across the sibling consoles is customarily identical except for the text language, the two 8-bit Maniac Mansion adaptations were wildly different products. According to Douglas Crockford, who helped manage the NES conversion, “we considered translating the Famicom version to English, but rejected it.”

And so Lucasfilm Games decided to shepherd the NES version itself. This being the studio’s first Nintendo game, they collaborated on the project with Realtime Associates, a proven console developer that was founded by a veteran of Mattel Electronics named Dave Warhol, who in between had also done audio work for game studios such as Lucasfilm Games, including on the original Maniac Mansion. The joined forces proved to be an ideal team, and despite the process of transposing the game being a drastic one (“It was heavily adapted,” confirms Crockford. “NES and C64 both used a 6502 processor, but everything else was different. The disk drive had to be replaced by bank switching ROM.”) the spirit of the original game was not lost on the other side of it.

This success has to be credited largely to the engineering work. Unlike the Famicom version, the NES game runs on SCUMM, adapted for the 8-bit platform by David Stifel, another prolific talent out of the Atari/Intellivision era. (The resultant version of SCUMM was, naturally enough, dubbed “NES SCUMM”, but this reference was stripped from the end credits at the request of a laughably sensitive Nintendo of America censorship board, which enforced its own stringent standards of “decency” on cartridges in the era before the ESRB.)

To accommodate limited screen real estate, the adapted system debuted a somewhat more streamlined interface with fewer verbs and a context-sensitive cursor (as in: the “What Is” verb from prior games is now implicit, with the sentence line immediately acknowledging an examined hotspot) – improvements more commonly identified with The Secret of Monkey Island, which was in fact released a month later. By being the complete opposite of a hack job, NES SCUMM also succeeded at retaining important, immersive features of the original game that the Famicom version did not, such as screen scrolling. This isn't a minor loss, as it was one of the innovations that was slaved over to make the 1987 game stand apart from its Sierra competition.

- Remi, probably.

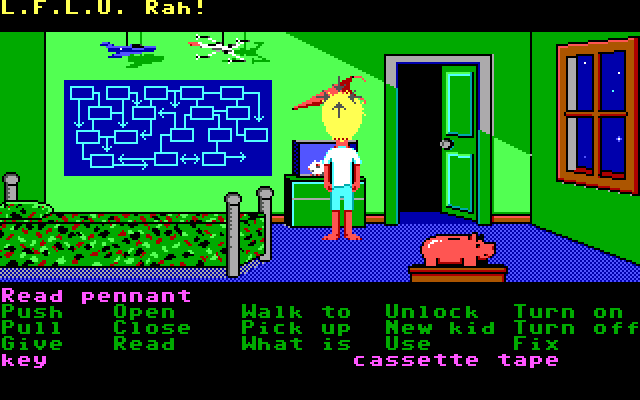

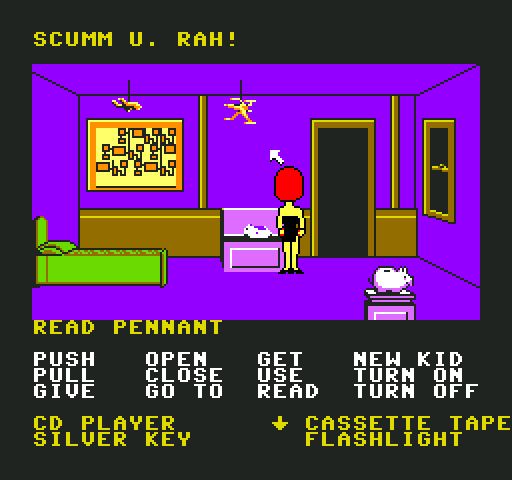

The NES artwork is similarly impressive despite having to be reworked from the ground up. Harrison Fong handled the backgrounds, while Mike Ebert was responsible for the character sprites. Both artists would go on to make major contributions to a number of well-regarded LucasArts console games, particularly during the 16-bit era. As a point of trivia, Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman have their first game credit on the NES version of Maniac Mansion, serving a role that Schafer later described as “object taggers.” Along with Jennifer Sward (Loom), the future project leaders were fresh-faced “SCUMMletts” at the time. Internally, the crash course that was used to train these junior programmers in the story system was called “SCUMM U”. A reference to this made it into the port -- note how the pennant in Weird Ed’s bedroom says something slightly different in the NES version compared to the original:

But for all these admirable efforts at fidelity, what makes the NES version really stand out are the enhancements it boasts, chief among them a full-fledged soundtrack. And it was implemented in a creative way: each of the playable characters possesses a CD player as a default inventory item, and all seven of them are looping a distinct tune reflecting their individual tastes. Razor is listening to punk, Jeff’s player is loaded up with surfer music, and so on.

David Warhol, whom we spoke to way back in 2008 for our big Maniac Mansion retrospective, recalled the genesis of this flourish:

We got about four fifths through development when Jaleco, the publisher, asked, "Where's the music?" There wasn't any music in the original computer game other than the title song and a couple incidental themes if I recall correctly, but video games at that time had to have "wall to wall" music. So Realtime was commissioned to get a soundtrack written at the last moment.

I turned to George and Team Fat to do some of the writing, and to Dave Hayes, a jazz/funk/fusion keyboardist living near Pasadena, to write some too. The guys wrote music on regular synths, and I gave myself the job of arranging them for the NES (having written the music & sound drivers, and being somewhat of an audio guy, myself).

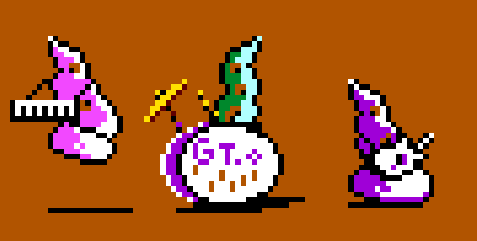

The “George” he refers to is musician George “The Fat Man” Sanger, who had also worked alongside Warhol on Loom (the engrossing soundtrack for which is a MIDI arrangement of Swan Lake) and would soon after become known as the frontman of “Team Fat,” a group with a long list of music credits in games and beyond. In the case of Maniac Mansion, Warhol tapped Hayes and Sanger to take on some of the game’s numerous tracks; Sanger in turn brought in future Team Fat member Dave Govett to further delegate some of the load. Per the end credits of the game, composition duties on the twelve named songs (which surely represent more than the average amount of original score for an NES game – to say nothing of their genre diversity) were evenly distributed among Warhol, Hayes, Sanger and Govett, with Warhol serving as the overall conductor, performing the final arrangements and implementing the varied soundtrack as a whole.

Warhol, whose company is credited on countless console games, was something of a pioneer when it came to implementing music for the NES. The parameters of the target platform were strict and eccentric, with every note and "instrument" a negotiation. A degree of innovation was necessary to leverage the full potential.

His solution was a driver of his own design, which was tricked out by the time the Maniac Mansion gig came around and yielded results that to some ears distinguishes Realtime's NES audio from that of other vendors. Abstracted from the tech, the other musicians on Maniac Mansion simply composed their MIDIs in the software of their choice (Cakewalk was the preferred program for Warhol and Hayes, while Sanger was partial to Performer) and delivered to Warhol in that form; Warhol would then use his driver to convert the digital data into a text format that the Nintendo could understand. Warhol spoke in detail about the conversion process and the level of efficiency it demanded to VGARC in 2016:

MIDI files are way too large for an 8-bit cartridge for memory footprint, So my processes always read MIDI files, compressed them using very specific 5-bits per-note instructions, and then 3-bits per-duration. So I was able to get a note into 1 byte, instead of a MIDI command which might be 3 bytes for note on, 3 bytes for note off. That’s 6 bytes per note, that’s way too expensive. So I took it all the way down to be 1-byte per note on/ note off, except for some patches (that) might’ve required 2 bytes, but yeah, very, very conservative with memory.

Something of a signature of Warhol’s 8-bit driver is its ability to produce an “echo” effect that he believes he debuted with Dick Tracy and is recognizable throughout the Maniac Mansion soundtrack. And hey, with all this background out of the way, what say we get on with listening to it? Join me on the next page, and the heart of the article, as we go through each track -- where possible, with the musicians responsible.