Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #10: Full Throttle Our Review

Tim Schafer, today widely praised as one of the most creative and important figures in the games industry and who was last seen charioted by four skimpily clad dames onto the stage of a spectacularly obnoxious awards show, had the humblest of beginnings. Joining Lucasfilm Games in 1989 as an "assistant designer/programmer," he embarked on his career as an uncredited tester on the loathsome Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade action game, after which he was put to work tagging SCUMM objects for the NES port of Maniac Mansion. Following his SCUMMlet training, Schafer served as a writer, designer, and programmer on the first two Monkey Island games along with fellow employee and budding adventure god Dave Grossman, and their first roles as project leaders was together on the classic Day of the Tentacle. With his next project, the 1995 release Full Throttle, Schafer was the lone head honcho for the first time.

Reflecting on the previous games he'd worked on, Schafer noticed a trend: they starred hopeless goofballs, albeit lovable ones. Characters like the nebbish Guybrush Threepwood or the clumsy Bernard Bernoulli were loads of fun and the providers of many a hearty laugh, but they weren't people you would necessarily aspire to be if they existed outside the realm of your computer monitor. Noting this, Schafer conceived a philosophy that lead video game characters should function as wish fulfillments of some kind, that there is an unquestionable appeal in being able to play as someone who can do things that we can't - fighting people on a motorcycle, being the Grim Reaper, having psychic powers - but that we might like to.

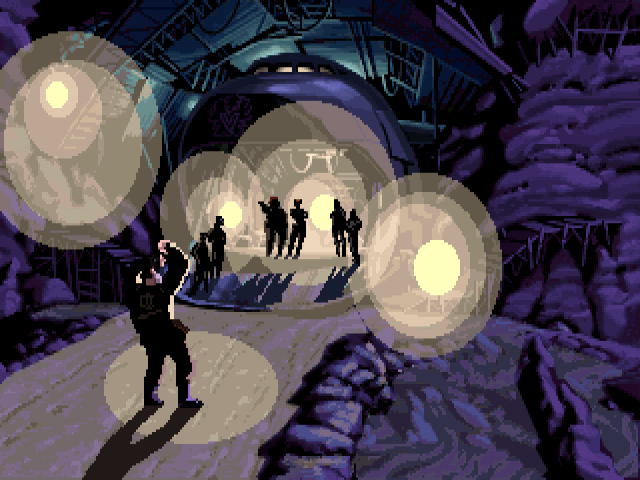

In Full Throttle, you guide the actions of Ben Throttle (called only Ben in the actual game for legal reasons), the cool, ripped, tough-as-nails leader of the Polecats, a notorious biker gang. Their rivals include the Vultures, the Rottwheelers, and the Cavefish - a strange, cave-dwelling tribe that see through special goggles. The game takes place largely on the highways of barren, desert landscapes of what might be described as a grim near-future where cars that can hover slightly off the ground are becoming commonplace, and the tribe-like biker gangs are threatened by a an automotive industry that has all but surceased motorcycles.

The game begins with the arrival of Malcolm Corley, the elderly, fun-loving head of the Corley Motors empire, and his sinister vice president Adrian Ripburger (voiced by the impeccable Mark Hamill) at the isolated roadside bar The Kickstand. There they try to recruit the Polecats as escorts to the annual shareholders meeting, ostensibly as a marketing gimmick. When Ben turns them down, Ripburger and his accomplices hand him a two by four headache and commence a scheme to frame him for Corley's murder, which Ripburger later carries out with great relish to ascend to power in the company. Using his fists, his wits, and… mostly his fists, Ben must clear his name, save his gang from an ambush, and restore the integrity of Corley Motors by supplying its proper successor – Corley's renegade, expert mechanic daughter Maureen - and preventing Ripburger's minivan-heavy vision. The game's tone is established as quickly as it boots, with the LucasArts logo giving way to Ben baritone voice narrating over a slow tilt from the sky to the highway that stretches across the canyon-flanked desert floor. This opener roots us in the game's distinctive style, a kind of action/biker/noir/western/awesome.

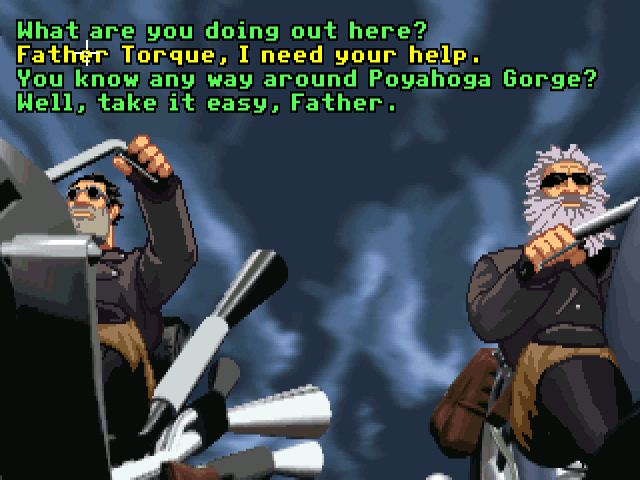

Despite the darker nature of the plot and characters compared to the exploits of Guybrush or Bernard, the game still to a large degree retains the trademark humor of LucasArts' adventures, which is particularly inevitable when you've got Schafer involved. As a result, the game comes off as sort of a dark comic book brought to life. The writing, handled almost solely by Schafer (Dave Grossman, in one of his final LEC credits, is enigmatically listed as "Additional Writer") is top-notch, and one of the reasons the game has such a professional, cinematic feel that particularly stood out at the time, and hold up. As with Day of the Tentacle, the dialog trees are relatively sparse but always entertaining. The game world feels well-realized and detailed - landmarks like Poyahoga Gorge and their histories are elements that we feel like we know as well as if they were real - and without burdensome levels of backstory. From the cold opening to the surprisingly bunny-laden credits, Full Throttle is a fine example of tight, effective storytelling.

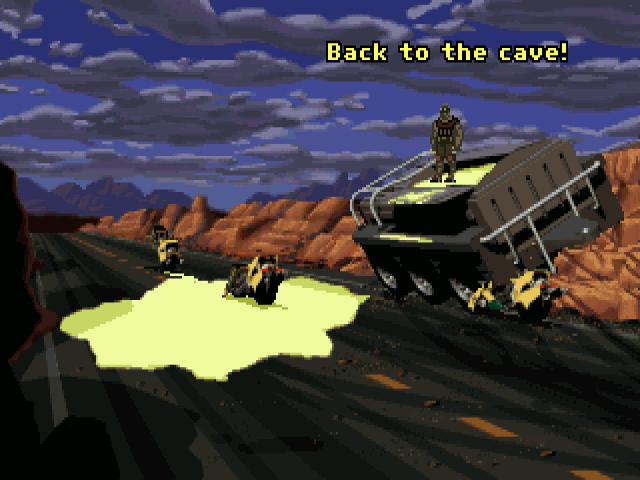

The grittier tone isn't the only way in which Full Throttle is a gear shift from what preceded it. It is a more action themed adventure game, reflective of a lead character who uses his muscles as much as his smarts to get the job done. Although this is a pure adventure game, action sequences are abound (mainly in the form of one-on-one fights that take place on speeding bikes), because the world and the characters who inhabit it demand it; their inclusion feels true to the material. The biggest mistake Full Throttle could have made would have been to have Ben spend the entirety of the storyline solving inane combination puzzles or partaking in tedious fetch quests. Bernard may think locating the key for a locked door would be a valuable expenditure of his time, but Ben would just kick the damn door down. It's an example of gameplay dictated by character personality.

The point 'n click interface is a relatively progressive one, and its goal is streamlining. The Sierra style interface of Sam & Max Hit the Road is abandoned (though that game's use of a screensaver, here being spinning 3D models of vehicles, is carried over), and came continues the trend of peeling the excess off. Full Throttle's interface is visually unobtrusive, and like Sam & Max leaves the entirety of the screen real estate for the in-game visuals. Instead of verbs or icon cursors, the four actions - represented by hand, foot, eyes, and mouth - are available in the form of a skeleton tattoo that pops up around a hotspot whenever you click and hold on it.

Ben's inventory never gets much bigger than a handful of items, and they can never be combined, eliminating the opportunity for the game to throw you puzzles that are more convoluted than they need be. (The only action you can perform on an inventory item is looking at it.) Over every exit on a screen, the cursor turns into a large red arrow, indicating that you can double-click out of it immediately instead of watching the second hand of your watch run its miles while your character walks across a vast environment. While I wouldn't call any of the previous LEC adventure games unintuitive, Full Throttle really takes the simplicity to another level in an effort to keep the separation between the player and the experience minimal.

Visually, the game is stunning, owing once again to the amazing efforts of Peter Chan (Lead Artist) and Larry Ahern (Lead Animator). Presented in a style that's a combination of gritty and cartoony, the caliber of the 2D visuals is entirely a credit to the artists who rendered them, even if the tools they had to work with enabled them to do things that simply weren't possible before. Indeed, while things look blockier than they would today, the art direction of Full Throttle hasn't aged a day, and would hold its own against a well-drawn graphic novel, its most appropriate comparison. The high production values extend to the excellent animation, which once again surpassed anything LEC had done up to that point. As an added bonus, the lip synching during the close-ups is actually successful, something that had flummoxed the Loom voice effort a few year before. It all adds up to the creation of a universe that's rich and compelling, and it's a distinction that makes Full Throttle, and indeed all the LEC classics, so worth revisiting.

There's nothing mixed about the quality of the audio side of things, an area of their games that LEC was always known to consistently nail. Although the first few attempts at Talkies were nothing to sneeze at, Full Throttle truly elevates the bar, and is so professionally done than it holds up even better than the visuals to this day. With a cast that includes many Guild actors (a first for a video game) such as Roy Conrad, Mark Hamill, Hamilton Camp, and Maurice LaMarche, Full Throttle exudes the authenticity of an animated feature, and set a benchmark for voice acting that the company would only continue to raise. This is the first LEC adventure game where I wouldn't even consider putting the subtitles on.

The moody, ambient-heavy soundtrack makes effective use of iMUSE is supplied by regular Peter McConnell, but in addition to the synthesized score Full Throttle uniquely (for the time, at least) features recordings performed and voiced by real life rock band The Gone Jackals. (Their still-available album A Bone to Pick features the music they provided for the game.) The selected tracks are employed appropriately and bolsters the movie-like feel, adding a touch of authenticity.

Although widely praised, Full Throttle is commonly criticized for two things – things that coincidentally are also lobbed at a previous LEC adventure game, Loom - its length and its difficulty level. And like with Loom, I feel that these complaints are wrongheaded. The game is indeed shorter than the likes of Monkey Island or Fate of Atlantis but, unlike those games can be at times, not a second of Full Throttle's duration - which feels about as long as a movie - feels wasted. Should a game's quality be measured by its scope, or how successful it is within the one it sets for itself? Full Throttle is exactly as long as it needs to be. And I suspect that the difficulty complaints are mainly just another manifestation of scope problem – relatively fewer puzzles result in the perception that the game's easy. If a game is given the respect of being valuated in a more meaningful way than with a stop watch, I think the popular complaints against Full Throttle are exaggerated.

To me though the only gripe with this game worth writing home about comes in the implementation of its action sequences. As stated, they're welcome and conceptually sound, but how the scenes actually play is a different matter entirely. To put it lightly, some of the attempts made here may have been more ambitious than the SCUMM engine was prepared to serve. One gets the impression that the programmers were trying to push the engine beyond its boundaries, particularly in the Old Mine Road stretch in the middle, which borrows the INSANE engine originally developed for Rebel Assault, and later the keyboard controlled demolition derby sequence. Nonetheless, these parts are highly playable and generally require the application of the mind over reflexes – their primary fault is being noticeably less spectacular than the rest of the game. And for players who just can't get past the bike fighting the normal way, the game includes a instant victory command (Ctrl+V), the equivalent of the Fate of Atlantis sucker punch.

Beyond that, negatives are hard to put one's hands to. At times the puzzle solving can get a little devious, but it's a relatively minor complaint and of LEC's entire adventure line-up it's probably only inferior to the superb Day of the Tentacle in terms of fairness. That's probably my inability to figure out the gasoline hose puzzle, though. The puzzle design deserves praise, as it is clever and seems to be geared more toward advancing the plot and entertaining the player rather than frustrating them. Most importantly, however, is none of puzzles are filler.

The game was most commercially and critically successful, and was in fact LEC's biggest adventure hit up to the time, After Schafer left LucasArts in 2000, a sequel (or two) was attempted, but the projects fell apart. Though the production stories make for good reading and it's interesting to get a glimpse of what might have been, it's just as well. The world of Full Throttle is a great one, but it's not exactly one that begs to be revisited when the story told in the first game felt conclusive enough. With Schafer not involved and the actor behind what instinctively feels like the irreplaceable voice of Ben deceased, there was ambivalence about LEC's attempts to continue the franchise then, and its rejuvenation doesn't seem any more likely now. Ben is a character probably best left riding off into the sunset rather than forcibly dragged back for another adventure just because fans were left wanting more. Just ask Indiana Jones.

Inspired and excellent, Full Throttle is yet another classic in LucasArts' adventure catalogue, a library that doesn't seem to have any bad apples. Of any video game I can think of, replaying Full Throttle is the most like re-watching a movie - even knowing all the puzzle solutions, playing through the game is worthwhile just to re-experience favorite moments. The technical and gameplay innovations it made may be hard to notice for the majority so many years after its release, but what's not difficult to see is why Full Throttle is yet another LEC title from the glory days that deserves its purported position as "masterpiece," "classic," or whatever superlative you can think of. It applies.

Yeah, when I think of Full Throttle I think of two things: Innovative and Classic.

A review by by Jason, who surely was thankful when she blew his gasket.

Four and a half out of five Murray skulls

Pros: Excellent writing and visuals; compelling world, story and characters; commendably streamlined gameplay; super-polished; awesome voice acting and music.

Cons: Action sequences good on paper, less good in practice