Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #1: Maniac Mansion Our Review

This is the first part of our "LucasArt's Secret History" article series, where we take a good hard look at all those great adventure games that LucasArts used to make. Special thanks to Dan "Jayel" Lee, who designed the Maniac Mansion header image for us.

Jim Ward, the current president of LucasArts, apparently sees these old games as embarrassing baggage rather than a legacy to build on -- prove him wrong by telling other people about these games, or reminding them how great they were!

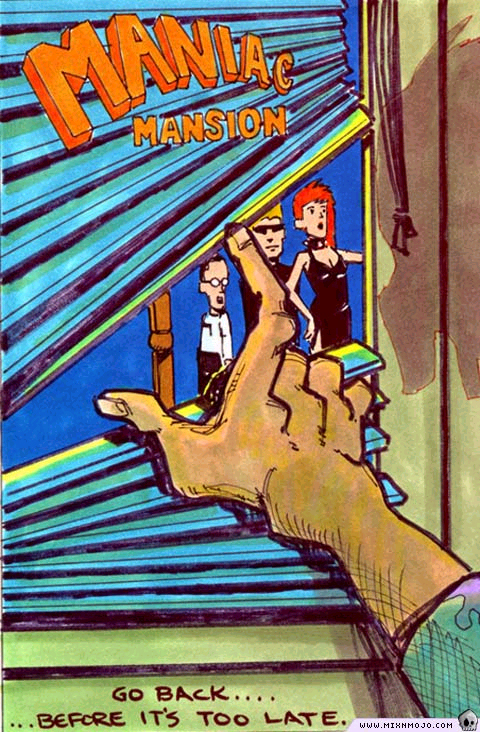

Twenty years ago today a slimy purple meteor crashed into the front lawn of the Edison mansion, and a revolutionary graphic adventure was released by Lucasfilm Games. Running on some nonsense called the SCUMM engine, Maniac Mansion lovingly sent up B-movies with the story of a trio of college students who break into a rundown, secluded Victorian mansion in the middle of the night to rescue Sandy Pantz, the school’s star cheerleader and Dave Miller's (the leader of the impromptu rescue mission) girlfriend. Sandy has been kidnapped by local mad scientist Dr. Fred Edison, and despite the discouragements of a sign that warns of assured mutilation and a welcome mat that reads, "Go away!" Dave and his diversely talented friends head into the mansion to retrieve their friend before her brain is lost to the good doctor’s "Zom-B-matic" machine.

Along the way, the teenagers will encounter the mansion's inhabitants, a kooky cast of threats and unlikely allies. The moderately dysfunctional Edison family consists of Dr. Fred, his repulsive wife Nurse Edna, their hamster-loving, commando-aspirant, accurately named son Weird Ed, a pair of pet mutant tentacles, a mummified cousin, a man-eating Venus Flytrap, and a sentient, evil meteor dripping with purple slime who may be involved with Fred's sudden desire to rule the world...one teenager at a time. It's up to the three kids (one being Dave, the other two being chosen from a lineup of six) to contrive a way into Fred's secret lab before it's too late not only for Sandy, but for the planet at large.

The brainchild of Ron Gilbert, a household name within whatever household shelters adventure lovers, and artist Gary Winnick, Maniac Mansion introduced a recognizable interface that would change story games forever. Featuring much-boasted point 'n click gameplay with no necessary keyboard input, players interacted simply by clicking on a verb at the bottom of the screen and subsequently an object in the game world to create a sentence and carry out a desired action. This mechanic contrasted greatly with the parser-based adventure games that were in vogue, eliminating the tedious and often aggravating challenge of having to figure out what the developers wanted you to type and instead allowing the game's intended obstacle, the puzzles, to be the player's primary one. Sure, the game's presentation is rudimentary by today's – or even Monkey Island 1's – standards. But seeing as most graphic adventure games of the time were of the parser-based variety, chief among them archrival Sierra's classic King's Quest, it's pretty clear that this game, hot off the heels of other innovative strides in the genre by ICOM Simulations (whose clear influence on SCUMM is rarely underlined), made the important first step that enabled the later and even more acclaimed adventures of Guybrush or Manny Calavera to even be possible.

Though it's harder to see when you stack the game up against the infinitely more refined titles it laid the foundation for, Maniac Mansion was a highly forgiving, logical, and seductive graphic adventure in the climate it was born in. It does indeed contain what are nowadays considered cardinal sins for the genre – the ever-present threat of death and worse, dead ends – yet many of the design philosophies established by Maniac Mansion are landmarks, blueprints for what was destined to be the reinvigorated genre's golden age. Instead of seeing your character killed for simply picking the wrong door (not all that uncommon even in adventure games produced years later), the ways you can perish in Maniac Mansion are relatively few, and occur under semi-reasonable circumstances that the adroit player will likely hit the save key before walking into. The puzzles, while zany, aren't exclusively trial-and-error based, and a character's inventory doesn't require a bookmark. These are hardly characteristics to be taken for granted in adventures of the era and reflect Maniac Mansion's considerably refined and re-focused approach to story-driven games that would prove to be a turning point for the genre.

The usage of three playable characters to be switched between at will for collaborative solutions - a handful of puzzles require creative use of multiple kids, and the unique ability of each has a bearing on how you complete the game - and the generally high level of nonlinearity collaborate to make Maniac Mansion one of the more complicated and ambitious designs in the LucasArts adventure catalog despite being the earliest.* At the same time, there's something about the game's confined (though certainly large) setting that always makes it seem solvable even when the puzzle you're attempting to crack is somewhere south of logical. This is in my eyes one of game's most endearing qualities - the scope is not such that you'll ever feel overwhelmed, and completing one of the game's solutions seems somehow in reach even when you're completely stuck. Yes, "one of," as one of the game's heralded and somewhat cutting-edge features is the inclusion of multiple endings. There are nine total, and they are dictated by the kids you choose and how you lead them to a successful (or unsuccessful) conclusion, giving the game more replay value than what is usually true of a graphic adventure.

In addition to its game-changing interface, Maniac Mansion is notable for being one of the earliest pioneers of cutscenes (and in fact coined the term), which periodically interrupt the gameplay to move the story forward, and mostly involve the Edison family's activities elsewhere in the mansion. Among these are key events that are triggered by an internal clock, such as the delivery of a package or the systematic shutdown of the mansion's power. These scenes contain the majority of the game's dialogue, since, unlike later LucasArts adventure games, Maniac Mansion is devoid of conversation trees and "in-game" lines are scarce. These scripted sequences capture the wacky, tongue-in-cheek personality of the game, which draws inspiration from cheesy, low-budget sci-fi flicks; everything from rocket-powered Edsels to home installed nuclear reactors find a place in the entertainingly oddball plotline. And despite the tragic absence of a "Look at" verb in your arsenal, particularly curious players will uncover a few amusing lines for specific actions (largely written by scripter David Fox) that hint at the rich interactive humor future SCUMM games would have to offer as the vision for them matured.

Though all of the above extolling is sincere, I hate to only praise the game in terms of historical value, because that underlying theme is something I tend to get annoyed with when people discuss it. "Maniac Mansion is an important game, but it's not a very good one," is the implication I sense from most people who write about it from a modern perspective, as if its value is strictly in an academic sense. Well, that's foolishness. The Secret of Monkey Island may have been the LucasArts adventure that truly brought things to a boil in terms of design, writing and production values, but Maniac Mansion is a great game that can be enjoyed and appreciated independent of its historical significance. It was the first adventure game I ever played, and the experience was eye-opening - it captivated me in that incomparable way that only a good adventure game can and that no other game had before. My bias is boundless and shameless, informed as it is by nostalgic fervor that shaped the way I looked at games and even led me to launch a fan site at age eleven, but I will readily defend Maniac Mansion to this day as a fantastic game, not just a material one. A somewhat stunning number of fan remakes would seem to be a testament to the sort of passion it has stirred within devotees since it came out.

Of course, the game can't hide its age in a number of significant areas. Graphically, you're not looking at anything too detailed, and the art quality varies a bit depending on the version you're playing, but the wacky horror parody flavor is always well-defined by the semi-cartoony visuals, which contribute as much to the style and atmosphere of the game as 16 colors possibly can. Sounds effects and music suffer even more from limitations of the time – most of the effects are just some annoying beeps and bleeps, and the still catchy main theme is one of the few actual songs in the original game. It should be said, though, that the NES version has a rather excellent full soundtrack, which you can listen to for yourself a few pages upstream.

As the first SCUMM game, Maniac Mansion doesn’t exactly feature the most streamlined take on a recognizable interface. With a staggering fifteen verbs in its first release (the NES version whittled this down some), the bottom fourth of the screen contains a number of completely unnecessary verbs, including the lonely “Fix,” “Unlock,” and of course the fabled “What is,” which allows you to reveal hotspots by moving your cursor around the screen. Its primary use being to help you find the light switch in a darkened room, this function was later built in to the cursor, saving a few clicks and quite a bit of confusion.

Since cutscenes are triggered by an internal clock, the game is going to cut away when their time comes rather than based on actions you take, as is the case with later games. Aside from the pacing issue presented by finding yourself waiting for an event to happen rather than the other way around, this also interrupts gameplay undesirably – I'm not necessary interested in Weird Ed's concerns about his father when I'm in the middle of panickingly trying to refill the swimming pool with radioactive coolant in order to avoid a nuclear meltdown. As previously mentioned, the game contains pretty nasty dead-ends – don't even get me started on the paint remover. For this reason it’s important that you save not only frequently, but in multiple save slots (if the version you're playing affords you that luxury). The deaths, while often entertaining, aren't exactly welcome when they aren't fairly foreshadowed, a prime example being Bernard's attempt to show you what he knows (or, rather, doesn't know) about "Nuke'em Alarm" security systems if you commit the sin of directing him to a sign. The world of a LucasArts adventure game before 1990 came around could be a pretty dangerous place to be in.

As is the case with many successful computer games, Maniac Mansion was ported to a number of systems over its healthy lifespan. Following an initial release on the Commodore 64 and Apple II, the title saw a IBM conversion and later an "enhanced" graphics re-release for a crush of platforms. The most famous port was probably the excellent and unique (more on that later in the feature) Nintendo version, developed by the Lucasfilm team (unlike the Japanese counterpart for the Famicom, which is a weird beast to say the least). It was the company's first NES project, and there's a pretty interesting story behind it, documented in a widely circulated article by the project's manager, Douglas Crockford. It was an auspicious effort for LucasArts but turned out to pretty much be the only example among the company's short string of NES releases that wasn't terrible. I'm still hoping that LucasArts (or Jaleco, or Nintendo, or whomever holds the power) permits this game's release on the Wii Virtual Console someday.

Oh, and the game technically also saw a Mac release, albeit in the form of an easter egg as a game-within-a-game in the Mac version of Day of the Tentacle. Of course, platform compatibility is no longer an issue thanks to the venerable ScummVM, which can even run the NES version with extremely beneficial mouse support, denying any excuse for this to be on any LucasArts or adventure aficionado's "yet to played" list.

Maniac Mansion is ultimately more than a terrific video game or the father of the LucasArts graphic adventure - it's a classic in every sense of the definition. Quit being a Alex Ashby tuna head, grab your copy-protection code book and play it again or for the first time. And pardon the mess...it's all those brain donors.

Written by Jason, on whom the Hunk-O-Matic has no effect.

Five out of five Murray skulls

Pros: An absolute classic and pioneer of the LucasArts adventure tradition, wacky story and characters, good humor, immensely fun.

Cons: It’s a really old game, but get over it.

But wait, there's more! Witness Zaarin's take on Labyrinth, LucasArts' first adventure game.

Labyrinth is based on the 1986 Jim Henson movie of the same name of which George Lucas was an executice producer. He wanted a game based on the movie released at the same time and that's what he got. The game doesn't let you play as Sarah, the protagonist of the movie, but as yourself. A good idea since who wants to play a girl in an adventure game? Ho Ho! Crazytown!

Labyrinth, LucasArts' first adventure game, uses a different interface compared to the company's later games. It starts out as a text adventure reminiscent of Infocom's games from the same era, but with a slot machine-like interface where you use the arrow buttons to choose verb and noun. In other words, you don't have to guess the verb and noun the programmer thought of. When you enter the world of the Labyrinth, the game turns into a graphic adventure, but keeping the same interface. That was one of Douglas Adams' [of Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy fame] ideas. One of his other contributions to the game was the noun adumbrate.