Articles

Return to Monkey Island Reviewed Page One

Spoiler Images?

The only thing more unexpected than the announcement of this game was the ride it took us on. More than thirty years have passed since Ron Gilbert was last captain of the pedestaled series he initiated, and over that lifetime this impossible-until-it-wasn’t reunion between designer and brainchild has been burdened with the venerated infallibility of myth.

Of course, it probably didn’t feel like a burden during those decades that the project enjoyed the convenience of being a theoretical (except, perhaps, for the people who worked on the other sequels). If he’s human, Ron must have taken occasional satisfaction in the generation-long deification of his imagined comeback, the proverbial True Vision™ that figuratively stood in unassailable contrast with the Imitation Monkey Island status those other sequels, however well-made or intentioned, could never hope to transcend. Legitimacy isn’t a negotiation, after all.

Honest memories will testify that from the earliest days of the humble online community that cohered around the SCUMM games, the relationship with Ron’s published and hypothetical work in the Monkey Island series could skid into this Branch Davidian territory. However uncontroversial and sincerely held the opinion, rating the first two games as the series peak could often play less like a preference than an oath of loyalty, and it wasn’t uncommon practice for the subsequent sequels to be assessed against some conception of what Ron would have done. And you could hardly hear fans confidently extrapolate on what Ron would have done without smelling the incense burning.

“They’re either at your throat or at your feet.” What you can always count on with fanaticism is that it victimizes everybody in the end. When Return to Monkey Island was announced and the first “concerns” about its direction were raised by those who would have volume taken for consensus, my joke was: “Now it’s Ron’s turn to ruin Monkey Island.” It’s a rite of passage, really. That the very same people who all these years used Ron’s “vision” as a cudgel to beat on the other games – even other fans – should be the ones to react abusively toward his suddenly tangible creative decisions on Return was as predictable as the sunrise. Though I’m sure it was hardly worth it to Ron, one silver lining I choose to see out of all that nonsense is that he has probably never before felt so kindred to the project leaders of the intervening games. Ron Gilbert can finally take his place among the frauds who betrayed the vision of Ron Gilbert.

And like all those other betrayals, this one is plumb fantastic. Return to Monkey Island is a gorgeous, vibrant, hilarious, endearing adventure that manages to live up to its pedigree (already a stratospheric standard before you account for the whole return-of-the-messiah business) and deliver a certain closure to three decades of frustrated innuendo -- but not too tidily, of course. The biggest question about this game from the start was how Ron and fellow original recipe Monkey Island stalwart Dave Grossman were possibly going to walk the seemingly contradictory line of “picking up where LeChuck’s Revenge left off” while simultaneously functioning as a continuation for the series as a whole, and without giving anything away I can say that they’ve done so with more cleverness, aplomb and humor than even the most optimistic contingent might have seen coming.

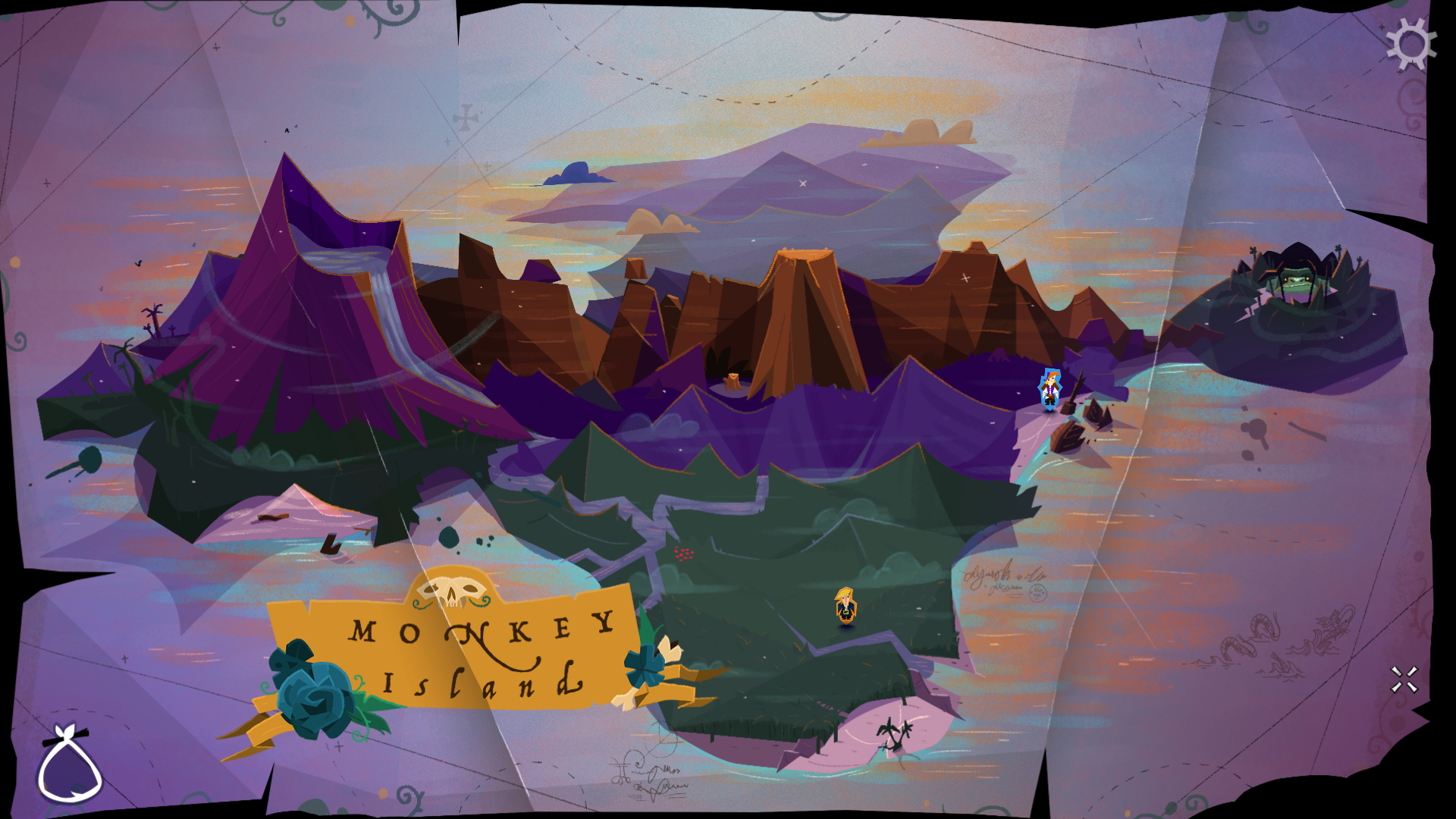

The curtain rises as advertised, on the ending of LeChuck’s Revenge. The very first moment of the game is among its biggest surprises, and exactly zero of the billions of fan theories that have been spun over the years predicted it. After a brief, tutorial-like setup, the story turns to Guybrush’s quest to find The Secret of Monkey Island…for real, this time. As the promotional media foretold, this adventure of unfinished business reprises key locations from the first game and much of its cast. This happened once before, in Escape from Monkey Island (though Return doesn’t share the fourth game’s amnesia about geography, with some consciously faithful re-imaginings of Mark Ferrari’s iconic Mêlée Island exteriors) and interestingly, the parallels to that particular sequel don’t end there.

Guybrush finds his old stomping grounds have changed, and not necessarily for the more inviting. An oppositional new guard led by the sneering Captain Madison has booted the old pirate leaders who dealt out Guybrush's three trials so many years prior, and a trendy "Dark Magic" has become the sorcery of the hour at the exclusion of tried 'n trusty voodoo, while several Mêlée Town standbys are shuttered or under new management. Old friends abound nevertheless: the Voodoo Lady is on hand at her original location to dispense wisdom and hexcraft, Carla the Swordmaster now occupies the Governor's Mansion, the even-more-grizzled Lookout maintains his post, Wally has relocated his mapmaking business to Low Street, and Otis and Stan are reliably keeping themselves into trouble. Even Cobb still hangs around the SCUMM Bar, albeit with a diminished enthusiasm for flogging Loom. Elaine, present but occupied, is off pursuing her own agenda in the Caribbean that contrasts sharply with her husband's self-glorifying one.

First on Guybrush’s to-do list - a literal one, which will be familiar to players of Thimbleweed Park - is that old canard of securing a ship and a crew so that he can set sail to Monkey Island. But this time there’s a twist: LeChuck himself is quite openly, and to a notable lack of a concern by the locals, docked at Mêlée, preparing his own voyage for The Secret. Not one to look a gift ghost ship in the mouth, Guybrush reckons the sensible method is to sneak aboard for a lift…and that’s about as much of the storyline that feels sporting to divulge. But don’t let the game’s surprisingly low price tag or the advertising’s emphasis on Mêlée Island fool you: this is a large, varied game, with a wide breadth of new locations and faces, and no meager supply of twists and turns.

Striking a balance between familiar and uncharted territory is tricky for any sequel, and it’s a particularly weird needle to thread this time out, for reasons that are difficult to get into without ruining surprises. It’s adroitly handled, though, and it’s not spoiling anything to confirm that Ron’s career-spanning infatuation with reality-undermining flourishes (whether it be the ambiguous kiss-off from LeChuck’s Revenge that in many ways created all the baggage this game has to answer for, or the truly unblushing and somewhat self-satisfied variation that Thimbleweed Park went in for) plays a role in how the Rubik’s cube gets solved.

All this on top of the already challenging tightrope any of these sequels have to walk -- that trademark Monkey Island balance between telling an engrossing pirate yarn and projecting a certain self-aware cheekiness borne out of the series’ essence as a send-up. Being a spoof of something and a “legitimate entry” at the same time is an impressive trick, and one that I think explains the endurance of comedies like Galaxy Quest, The Princess Bride (which the first Monkey Island game quotes more than dialog from, I always thought, and the homage really goes to another level with this one) or the best of Edgar Wright’s work. Even the Indiana Jones movies are essentially and recognizably riffs on the pulp fiction of the past, but with so much stamina and invention as to transcend the source and emerge as something new. It registered with me totally when I once read somebody diagnose Temple of Doom as “the Kill Bill of the 80s,” and I think that same phenomenon, where the perimeter of tribute gets blurred to the point where the distinction stops being useful, is part of the secret sauce of the Monkey Island series as well.

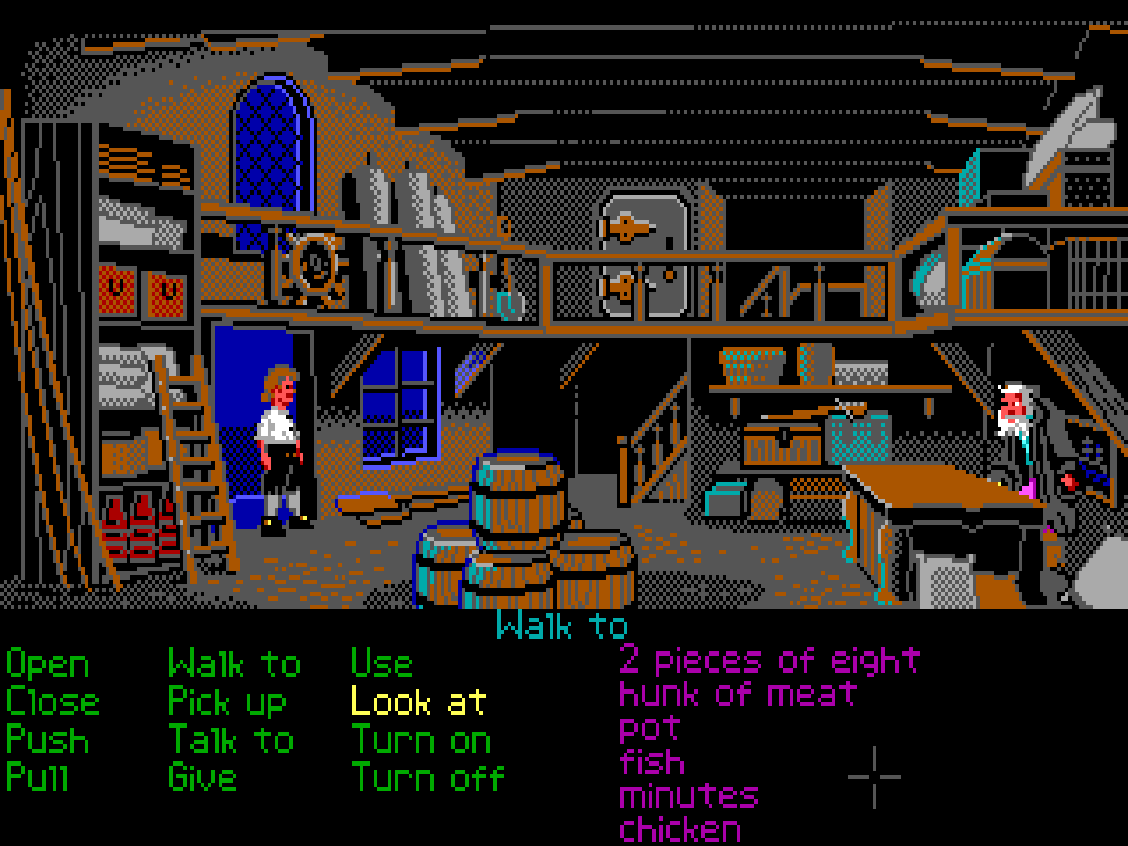

The balancing act extends to how low the developers deem fit to bow to genre convention. While Thimbleweed Park, Terrible Toybox’s previous adventure game, was a throwback as an outright agenda, Return to Monkey Island’s deference to tradition is a bit more considered, though never departed from to an extreme degree. Running on a new engine called Dinky, the game brings Monkey Island to 2022 in the most tasteful sort of evolution, retaining the core experience that any adventure game fan will feel right at home with, and one that I doubt will present any obstacle for newcomers, either. The most notable gameplay flourish is a particularly expressive new version of the context-sensitive cursor. When moved over an item of interest, it will present the one or two relevant things Guybrush can think to do, complete with his mental commentary. Remember that gag in Monkey Island 1 when Guybrush, tethered underwater, gives taunting new labels to the out-of-reach implements, emphasizing their sharpness? It's a little like if that concept were applied to the whole game.

I played Return on Windows (and look forward to trying out the Switch version, which I’ve pre-ordered but can’t claim hands-on experience with as of review time), and found a satisfying snappishness to the whole experience that I got from Thimbleweed as well; it just feels good. I’m gonna guess that Lead Programmer David Fox, another veteran of the LucasArts epoch (more than that, actually: he is the original SCUMM scripter, having played that role on Maniac Mansion and therefore having authored some of the studio’s earliest interactive dialog) is at least partially responsible for that satisfaction. Return for Monkey Island cannot be confused for anything other than a classic adventure game, but it avoids being precious in its judgment about what’s elemental and what can be cut loose, and it’s finetuned to a shine.

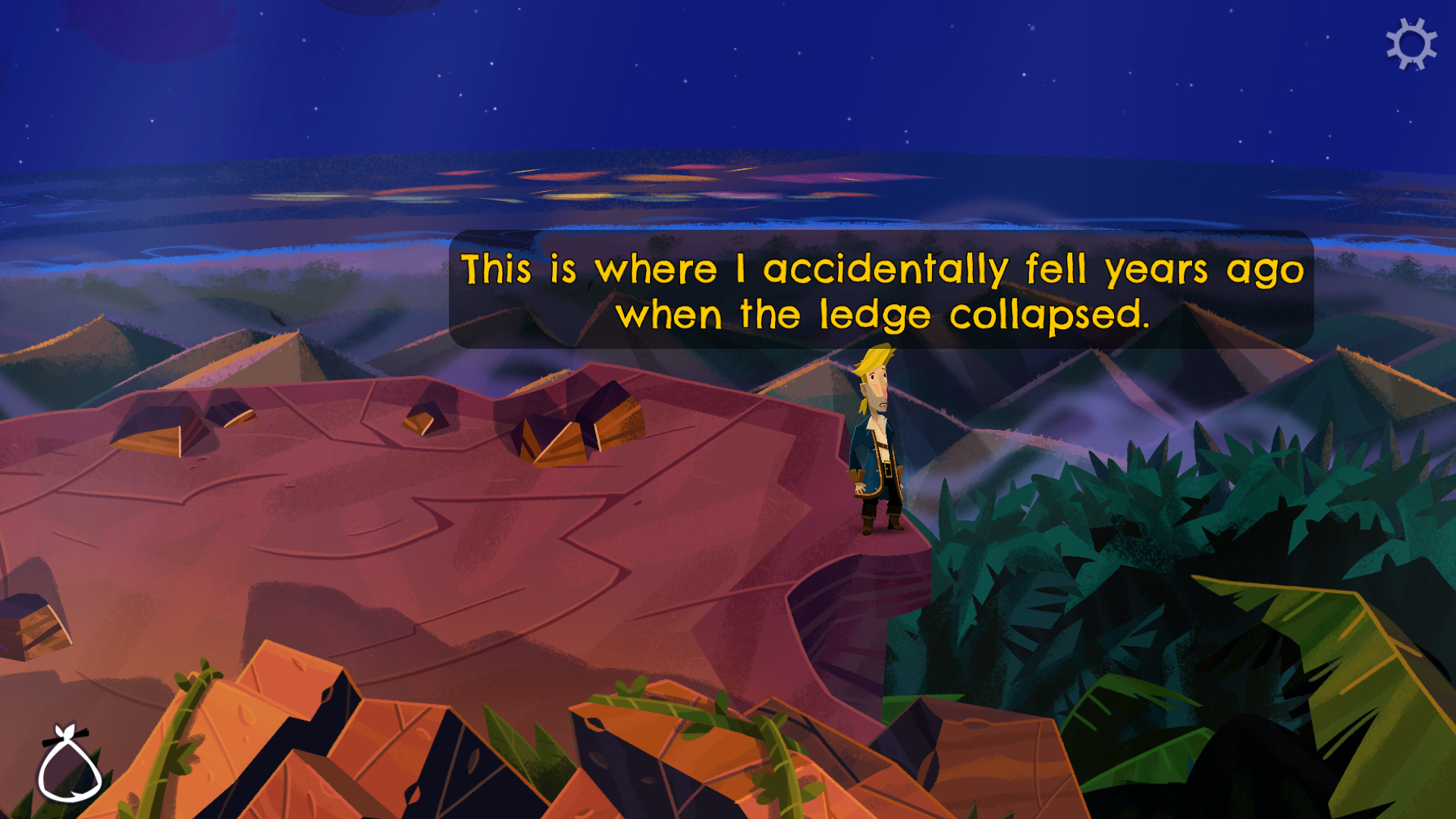

The game’s a visual knockout. Hand selected by Ron, an admirer for years, art director Rex Crowle and his team joyously continue the tradition of shaking up the series’ presentation with each outing. The jump between the first two games (which, being back-to-back productions, inevitably boast the most visual continuity) from EGA digital art to VGA scanned art was more considerable than is often given credit for, possibly in part because the 256-color revision to Monkey Island 1 (tastefully and brilliantly done, I’ll add) supplanted the original release version in the consciousness.

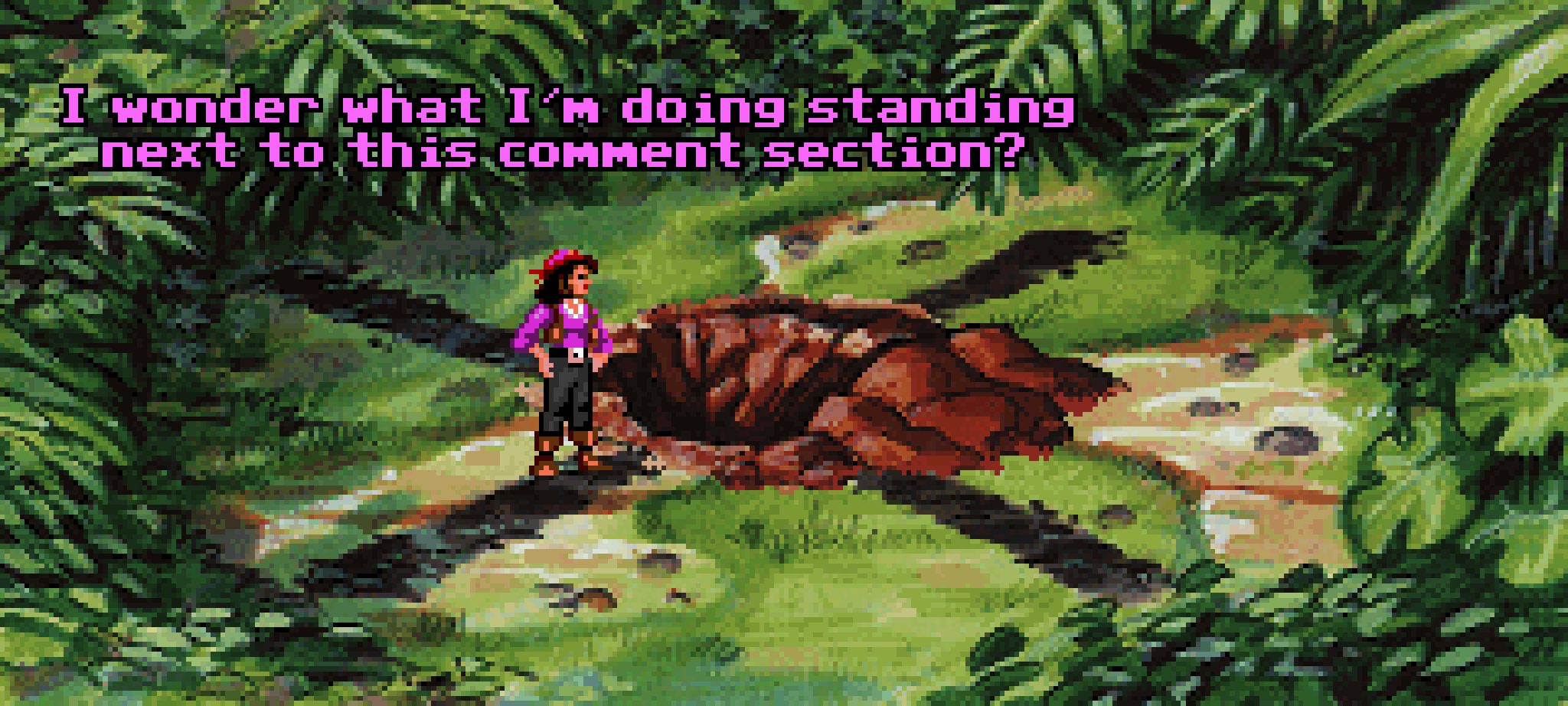

Under Larry Ahern’s art direction, the bar-raising The Curse of Monkey Island successfully pushed the series as close to the realm of feature film animation as a CRT monitor was ever likely to deliver in 1997; on Escape from Monkey Island, Chris Miles leveraged a background in animation to lead a manful if quixotic adaptation of a lush universe to the GrimE engine in the series’ 3D debut; with Tales of Monkey Island, Derek Sakai’s team guided a graceful, immersion-renewing move to the real-time 3D of the Telltale Tool under the gratuitous pressure of chokingly antagonistic target specs.

The hyper-stylized Return to Monkey Island comes off as less compromised than the previous 3D games, because it doesn’t feel as overtly like the product of tensions between intent and hardware directives but rather exactly what the art team set out to accomplish. Crowle’s “pop-up book” style serves the narrative (Guybrush’s compulsive memoir-keeping, once a marketing conception, has never been more relevant than in this game) and the senses beautifully; with no small assist from its brilliant use of animation and effects, the art is bursting with personality while proving able to accommodate the series’ deep capacity for atmosphere. Though any screenshot of the game flatters it, they do limited justice to the game’s overall presentation. You haven’t seen this until you’ve experienced it firsthand.

What ended up being the most exciting aspect of Return for me is the sense it gives of how the creative leads have evolved along with the series they hatched. Gilbert and Grossman have a different relationship with this property than they did when they debuted it (it’s startling to remember that the designer/writers were in their twenties at the time), and the same is true for their existing audience, many of whom met Guybrush during formative periods that aren’t so easy to separate in memory from the games themselves.

Thirty years have put all of us in a different part of our lives, and given a certain trend in this series of self-awareness (even if largely as comic fodder), there’s something of an opportunity to not just celebrate but reflect on a connection with the series that’s grown complicated by time. It proves fundamental to the vision Ron and Dave selected for Return. With a story that ponders themes of the march of time, the question of relevance and the nettlesome business of legacy, the game feels like an older pair of storytellers not only reuniting with a fond creation but in a way coming to terms with it. What this means for Guybrush shouldn’t be discovered by proxy, but while Return is laden with extremely overt reprisals, it avoids the trap of functioning as pure nostalgia exercise by having something on its mind. Plus, you get to learn the Voodoo Lady's name. I hope that bullet point makes it to the eventual box.