Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #2: Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders Our review

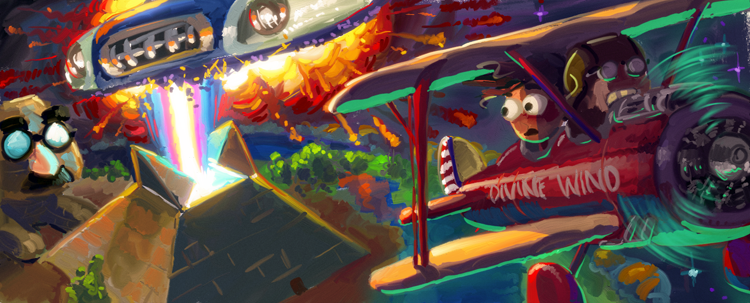

Welcome to the second part of our LucasArts' Secret History series: "secret," because of LucasArts' bizarre denial of everything they've done pre-2000; "history" because everything you read here is true and actually happened to someone, probably. Thanks once again to Dan "Jayel" Lee for Zak McKracken header image.

The first thing that becomes apparent pretty early on when playing Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, LucasFilm Games' (what LucasArts called itself before 1991, for those just joining us) follow-up to Maniac Mansion, is how epic it really is. While the first SCUMM game stuck you inside a single house to think your way through, Zak McKracken sprawls across a plethora of exotic locations that aren't even limited to our own planet. This geographically expansive adventure has you constantly traversing a whole lot of far-reaching and diverse places ranging from the Sphinx to Mayan temples to the Bermuda Triangle and beyond, creating a scope that I daresay the developer never successfully rivaled in any future efforts.

The storyline is set in the "futuristic" year of 1997 (the game was first released in 1988), and revolves around the titular Zak McKracken, a disenchanted San Francisco tabloid news reporter who would much rather embark on his novel than continue to take thankless assignments from his demanding boss, whom he lovingly refers to as "Fathead" – in his head, anyway. To complicate matters, Zak's nights have recently been best by a recurring dream, the latest episode of which is displayed during the opening credits sequence. The peculiar visions, among them a lot of bizarre and foreshadowing imagery, include the appearance of a beautiful woman. When he wakes up from the dream yet again and switches on the TV he learns that the woman is a real person, Annie Larris, who's actively collecting strange artifacts and, as it turns out, has experienced a dream similar to Zak's. And then there's Annie's friends, Yale coeds Melissa and Leslie, who have literally taken a trip to Mars after dreams of their own included instructions by an alien to convert their van into a homemade space shuttle. Meanwhile, and possibly in relation to all of this, the nation is suffering a severe "Stupidity Epidemic," or then again maybe people are just like that.

Zak's adventure begins on assignment, as Fathead has tasked him to investigate an ill-tempered two-headed squirrel who's supposedly been attacking tourists near Mount Ranier, the location of the first UFO sightings. While exploring the vicious animal's cavernous home Zak stumbles upon an ancient and mysterious artifact, a blue crystal, which finally gives him an excuse to meet Annie of "The Society of Ancient Wisdom," who explains her theory that their collective dreams are a message. Her interpretation of the dreams is that the beings transmitting them are prescribing the construction of a special machine powered by three crystals, Zak's new artifact being one of them. With the help of Annie and her two Mars exploring colleagues, the quartet work toward this goal while uncovering a devious plot by a unit of grotesque, and none too bright, aliens called Caponians to turn humans into helpless idiots – even more so than usual. This scheme they have begun to carry out by infiltrating the Phone Company and employing a heinous Mindbending Machine that will all but completely sap a victim's intelligence, not to mention their interface verbs. Can Zak and his new friends, apparently chosen by a benevolent alien race, foil the plot of the repulsive Caponians before it's too late?

Zak McKracken's plot draws from and kids a lot of inspirations, chief among them New Age concepts, tabloid journalism, ancient astronaut theories, and even the speculative whereabouts of Elvis. It has a lot of fun with its not-too-distant future setting, depicting the use of a universal "CashCard" for all monetary transactions and offering a tongue-in-cheek take on what a few notable locales will look like In The Future. Zak's gameplay inspirations, however, are less interesting, seeming to come exclusively from the kind of hardcore, frustrating adventure games that dominated the market throughout the 80s.

In our previous article I described Maniac Mansion as one of the most complex and ambitious of LucasArts' adventure games, despite being the earliest. Zak McKracken is subject to similar observations, but this time they're all pretty much evident to you right upfront. While Maniac was a complicated game in a deceptive way, Zak makes clear fairly early on that it will be deep, wide, and nonlinear. By the time the game gets fully underway, you're controlling four characters, two of whom are on Earth and two on Mars (with the notion of "dream-sharing" being used to explain their privies to each other's progress and discoveries) with very little in the way of direction. Zak is also a long game, and not just because the puzzles are insanely difficult and the world huge - there's simply a whole lot that needs to be done to direct your characters to a successful conclusion.

In this sense, Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders is probably the closest thing to a non-LucasArts adventure that the company ever made. By that I mean its target audience seems primarily to be the hardcore adventure gamer, when LucasArts games generally earned the reputation of being more inclusive. Not to speak in absolutes, but if you want a lengthy, head-scratcher whose intended selling point seems to be to test the limits of your sanity, this is a game for you. It's certainly got enough of the quintessential characteristics of its brethren to be recognized as a LucasArts title (polished and with thankful, noticeable attention toward story and characters), but it's probably the black sheep of their adventure product line if it's necessary to indicate one. This is not a jab at the quality of the game – for what it's trying to be, it's absolutely successful – but Zak McKracken is definitely in the "old school" mold, and is doubtlessly the most difficult adventure game in the developer/publisher's SCUMM library. As was the case with Maniac Mansion, it's significantly less insane than a lot of other adventure games of the time period, but among the elite group it was born into it's a standout for the sheer immensity of the gauntlet it throws. Don't bet on getting through this one without a walkthrough.

Despite the generally obscure nature of the puzzles, there is something that must be said about their design that affords you a certain level of respect, and reminds you where this game was built. The puzzles are next to impossible, but by Job, the designers really thought of every which way a player would possibly try to solve them. If there are three things in your inventory that you think would make sense for waking up a snoozing bus driver, or digging through a wall of dirt, or retrieving a CashCard from under a desk, this game makes sure all of them work. It's the kind of well thought out, if not logically motivated, puzzle design that you just don't see enough of in adventure games, even ten years later. There's an article that emphasizes Zak's merit in this regard over at Adventure Gamers called "That Doesn't Work!" that I recommend.

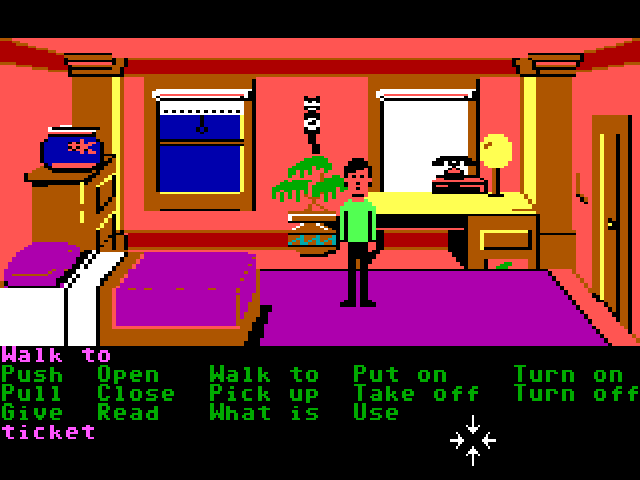

The game runs on the exact same version of the SCUMM engine that Maniac Mansion did, at least on the user-end (while some behind-the-scenes overhauls were made to accommodate the game's different goals). Consequently, my judgment of the presentation is similar to Maniac Mansion's. The art team was a bit bigger than Maniac's to accommodate the more ambitious locations both in number and content - pay attention to the credits to note Martin Cameron and Mark Ferrari making their debuts - but the visual style is comparable. Tech-wise, the graphics and sound are probably as good as they can be given the tools of the day. The version you play also has a huge bearing: the differences are not minor between the EGA, VGA, and exceedingly rare FM-TOWNS versions, the latter boasting 256 colors and a CD audio soundtrack. If you have a few hundred dollars burning a hole in your pocket, it may be something to head over to eBay for.

Aside from the love 'em or hate 'em nature of the puzzles, other faults that the game shares with its SCUMM-ushering older brother is the ability to get stuck and the rather frequent opportunities for sudden death. Due to the game's hugeness, these problems are exacerbated because in many cases there's just no way to know why you completely screwed yourself by forgetting to get that one object until you actually hit the dead end, by which point you may have wasted a lot of time making otherwise good progress. The game also comes with a few "sustenance" aspects that you need to constantly tend to - your CashCard credit for your Earth couple and your air supply for your Mars couple (essentially imposing a time limit, at least for awhile). While there's a point in the game where both of these things essentially become irrelevant, it's yet another hindrance for the player in a game that really wasn't screaming for a heavier cross.

Finally, there's the mazes. My God, the mazes. This game is full of them. It's positively filled to the brim with them. Now, back in the day mazes were a cheap (in terms of space) and effective way to pad the game's running time, but you'll probably find sympathy for such obsolete concerns hard to put your hands to while you're trudging through these frustrating and prevalent sections of the game, which seem to exist for no other reason than to ensure that you that whatever amount of gameplay hours the box boasted (sadly a metric for "value" that some still use for games) was fulfilled. Granted, many of the mazes are simplistic enough that just following the strategy of "keep going to the farthest end" will eventually lead you to salvation, but if there's any portion of the game where cuts could have been made, this is it.

But the main problem with Zak, to the extent that it has one, is that it's simply too much. Is that necessarily a bad thing? Not for everyone, but I think it takes an unabashed lover of old fashioned of adventure gamers – a very much existent but waning audience – to fully appreciate what this one has to offer, and that's simply not a qualifier that tends to be necessary with these classics. It possesses a level of quality, intrigue and humor to earn its place in the LucasArts lineup, but it fails to be a game that's even nearly as accessible as its head-slappingly simple interface and inviting, light-hearted tone promise. The bottom line is that your enjoyment of this game is going to have a lot to do with how much you enjoy solving obtuse puzzles that will have you scratching your head for an indeterminate amount of time - and hey, there are definitely people who consider that to be fun. To anyone who questions this game's following, I direct you to a certain fan sequel as well as a number of impressively exhaustive fan sites.

If Zak McKracken is the one or one of the few LucasArts adventures that you haven't played yet, you really owe it to yourself to add it to your resume, but don't feel guilty about enlisting in some (or a ton of) outside help along the way. The second SCUMM outing isn't for everyone, but it's a solid, competently made adventure game from the classic era that delivers the goods – and then some.

Written by Jason, who only shredded, like, three goldfish max in researching this article

Four out of five Murray skulls

Pros: Amusing and enjoyable storyline that generates wacky humor. An impressive number of locations and use of multiple characters. Definitely get your money’s worth on length. A polished experience.

Cons: Poor pacing. Painfully difficult puzzles. A few too many mazes. Death and dead-ends frustratingly frequent. Overall an extremely intimidating game that novice players will not find welcoming.