Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #7: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis Our Review

LucasArts' mystical masterpeice is unearthed and uncovered in this, our VIIth Secret History Article. Whilst LucasArts beaver away on their "Staff of Kings" wank, we remember the best movie licence game ever made. (Thanks to Dan Lee for the header art.)

After the success of the Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade graphic adventure, it came as no surprise that LucasArts brass would demand another adventure game starring the globe-trotting archeologist. As all three of Last Crusade's project leaders were busy with other endeavors when the time came to get the sequel off the ground, a fella named Hal Barwood was given the reigns to this title, his first in the project leader role.

Initially, the game's plotline was to be based on a rejected screenplay for the third Indiana Jones movie, but, unimpressed with its quality, Barwood (himself a former screenwriter and film maker of some note, as well as a longtime friend of both Steven Spielberg and George Lucas) elected to concoct his own Indy yarn with some help from future cohort Noah Falstein, who was freed up to work on the project after all when his version for the eventually released The Dig was canned.

The decision to give Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis an original storyline was a wise move, but it was the care and attention put into the effort that was truly the key to the immense success that resulted. Barwood's background is no doubt a factor in why Fate of Atlantis feels film quality, which is not merely a compliment of the game's story, but of its dialogue, characters, tone, and other strengths that combine to lend the game an overall cinematic feel. In fact, not only is this game legitimately Indiana Jones in its every byte, the game stacks up favorably to the films themselves.

Before the notion of a fourth Indiana Jones motion picture ever seemed like a genuine possibility, fans often nicknamed Fate of Atlantis as Indy4. It's an appropriate enough title, as anyone who's played the game can attest to - it's good enough to be considered a follow-up to the trilogy. Heck, multiple fan-made sequels have been attempted to honor the game, some of which have been in development for many years. Fate of Atlantis is in all the best ways the exact opposite of what you'd expect from a product based on a movie franchise and is by far the most beloved of Indy's interactive adventures.

The adventure is set in 1939 (putting it shortly after the events of Last Crusade in the character's rather leaky but nonetheless documented timeline), and opens with Indy recovering a strange statue from Barnett College's rather perilous attic archives at the behest of a mysterious Mr. Smith. Upon taking the unusual horned relic from Indy by force, he reveals himself to be Klaus Kerner, an agent for the Third Reich. It turns out the Nazis are furiously looking for any artifacts they can find connected to Atlantis, and Indy's statue fits the bill. The Germans, led by the high-pitched, nefarious mad scientist Dr. Ubermann, will stop at nothing to discover the Lost City, and their intentions are naturally unwholesome. They endeavor to amass orichalcum, an Atlantean metal in bead form that is capable of fueling weapons exponentially more powerful than the atomic bomb, and which also serves as the power source for all of Atlantis' advanced and enigmatic machinery, the purpose of which may be more than bargained for by those who desire to take wield its powers.

In his quest to foil the Nazi's scheme, Indy reluctantly partners with Sophia Hapgood, former team partner from an Iceland expedition a decade earlier whom Indy has reason to believe the Nazis are after. Indy and the independent red-head did not leave off on amicable terms, and there are tensions between the two. A self-proclaimed psychic, Sophia wears a peculiar necklace she pillaged from the Iceland find which she believes to be Atlantean in origin, and which she claims allows her to communicate with Nur Ab Sal, a former Atlantean king whose spirit guides her decisions. Though skeptical of such "hocus pocus" (as he always seems to be at the start of one of his adventures, despite having quite a bit of experience with the supernatural), Indy and his rebellious companion, guided by a rare manuscript called The Lost Dialogue of Plato, race to beat the Nazis to the subterranean city-state before they can unlock and harness its secrets for world domination.

Like the movies, Fate of Altantis draws its influences from a volume of different cultures, myths and histories to concoct its entertainingly far-fetched yet well researched tale. The writings of Plato in particular serve as prominent inspirations for the game's story. For instance, it was the Greek philosopher's suggestion that the fabled city was comprised of three concentric circles, a visual that the game uses prevalently, such as in the three stone disc keys which, configured the right way on a pedestal, grants access to the city and its lesser colonies.

The Nazi's faith in Atlantis as the home to ancestors of a supreme Aryan race is also based somewhat in historical fact, and the game borrows from popular legends about superhumanly advanced beings being responsible for Mayan architecture, or the notion that gods landed their spaceships on ancient outposts throughout the world. (I can't help but notice that a lot of these ideas, which also include a central character having a mentally consuming psychic connection with one of the city's gods, have uncanny similarity to major elements of the later made Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. The main difference is that those elements are far better developed ere.) The game's tone and writing are as pitch perfect as the story they support, once again a credit to Barwood and Falstein. The humor of the films is also fully intact, but while the game doesn't take itself too seriously it doesn't play like a big joke either – in fact, it gets pretty heavy toward the end. Above all, the game feels true to its license.

The characters that occupy this original story in their handful of pixels exhibit personality that makes them worthy of their live action competitors. First, the game gives us a superior leading lady in Sophia, who is a strong, resourceful character functioning simultaneously as Indy's sidekick, foil and romantic interest, with her spirit being most reminiscent of Marion Ravenwood without being a carbon copy. She's certainly a more interesting Indy girl than Willie Scott or Elsa Schneider, and other official Indy storytellers seem to agree, as the character would have her services called upon for the next video game as well as some of Indy's paperback adventures.

For the villains, the in over his head Dr. Ubermann makes for an intriguing nemesis as he lacks the physical presence to complement his ideological treachery. Claiming victory over the nuclear race to split the uranium atom, Ubermann is obsessed with discovering and unleashing the power that lay hidden within the undersea kingdom. His muscle is supplied by the sadistic Klaus Kerner, the Nazi henchman who follows in the tradition of sneering, sardonic types you love to root against. Indy himself is also nailed, his voice and nature captured perfectly, which is not the kind of thing you can take for granted. The bottom line is that even before the actual gameplay is considered, it's obvious that the Fate of Atlantis team made it a priority to make their mark on the franchise with reverence and an understanding of what makes an Indiana Jones story work. When it comes to Indiana Jones game or indeed license games in general, Fate of Atlantis should be a reference.

The opening sequence, which plays out as an interactive credit sequence, sets up the game expertly not by assaulting us with inventory puzzles, but by establishing the main character. With the full interface not temporarily erased, the player simply directs Indy around the college archives, and when something goes wrong Indy falls into the next room in a painful and unintended way. On top of just being an amusing and original way to start off the game, it's incredibly relieving, because you know right off the bat that the game gets the essence of Indy, a hero who, while always emerging victorious from his precarious and implausible situation, does so in ways that don't really go according to plan.

Running on a nearly identical version of the SCUMM engine as the simultaneously developed Monkey Island 2, Fate of Atlantis is another game that retains the company's tried and true gameplay, with an interface and overall presentation that relies more than anything on the delivering the experience rather than calling attention to itself. As is the case with most LucasArts adventure games, progressions in technology are acknowledged, but are an enhancement rather than an imposition.

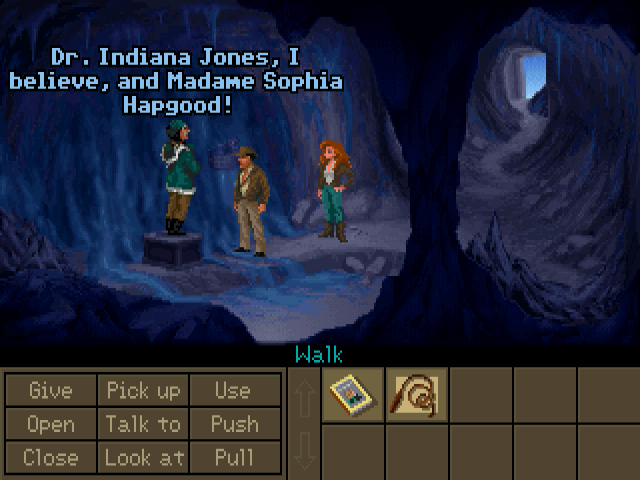

Although budget constraints prevented Fate of Atlantis from taking advantage of the then spanking new scanner technology that the concurrently developed Monkey Island 2 utilized, the game's 256 color VGA "pixel paint" backgrounds are nonetheless gorgeous and lend the game a thick atmosphere. Like you'll hear me say time and time again, there's just nothing that compares to good artwork, regardless of its age or the technology used to render it. Naturally, the cinematic origins mean that the game has a more realistic look than any of the prior SCUMM adventures, but none of the over two hundred (even for a big adventure game, that's an abnormally large number) locations are realized in a drab or uninteresting way. On top of just being eye-pleasing, the art in Fate of Atlantis is incredibly diverse. That's because like any good Indy yarn, the characters are taken to a large number of exotic locales around the world, giving the art team (led by the immortal Bill Eaken, coming off of a collapsed phase of The Dig) a plethora of locales and a wide range of scenery to work with, from 1930s New York to Mayan temples to Algerian deserts to the island of Crete to Atlantis itself.

The visual interpretation of Atlantis, borrowing heavily from Minoan styles, remains haunting. Instead of giving us a glorious, pristine, romantic version of the Lost City, we get a dank, eerie, sewery remnant of a strange civilization laden with deformed skeletons and that, while every bit as advanced and spectacular as the stories surrounding it would suggest, definitely has an undeniably ominous quality to it. It's as Indiana Jones a domain as I can fathom, and in a game that can pull of a wonderfully…creepy…mood when it's called for, the design and execution of the climactic location gives this off most powerfully.

For the animation, LucasArts used for the first time the technique of rotoscoping, which enabled the character motions, such as Indy using his trademark whip, to appear more lifelike. Thanks to the amount of animation (very much akin to quality and prevalence of that of Monkey 2), Indy, his friends, and his enemies are given considerably more life than could be said of Last Crusade, which had far fewer examples of (no less impressive) animation. Backgrounds are given the subtle, effective touches in the form of rippling water, soaring birds, or the busy locals of a crowded market.

Like its sister production Monkey Island 2, Fate of Atlantis is one of the lengthiest and most complex adventure games LucasArts ever produced. In a time when adventure games are forced by modest budgets to trend a bit toward the simpler side (though not always for the worse, it should be said), Fate of Atlantis certainly brings us back to a long ago era where the scope of a story game could be nearly limitless. Certainly, the designers did not cut themselves a break when they laid out the structure for this game.

The ever talked about Three Paths feature remains as impressive today (when such an ambitious idea would probably never survive beyond a design document) as it did back then. For those unfamiliar with the game: there's a "crossroads" moment relatively early on in the story where Indy and Sophia are in conversation, and Indy (the player) is allowed to decide between three options to continue the adventure. Nicknamed by the manual as the Team Path, the Wits Path, and the Fists Path, these three separate routes through the bulk of the game's storyline allow players to enjoy the adventure based on their preference for action or puzzle solving, and gives the game a degree of replay value that is generally unheard of within the genre.

You will still experience the same general story no matter which of the three paths you take (and they do converge once Indy reaches Atlantis), but since they all have their own puzzles, situations, and in some cases, exclusive locations, this crazy undertaking of a design decision makes it impossible to see all of the game's content in a single playthrough. In addition to all that, the game features an alternate ending based on whether or not you successfully save a character, similar to the option of killing off Dave in Maniac Mansion or letting Elsa choose her own doom in Last Crusade. These extra efforts make Fate of Atlantis worth playing again and again.

A game this brilliant isn't ruined by its flaws, and in the case of this game the major flaw is the puzzle design. I won't name any specifics, and as I'll say of any LucasArts product the puzzles are infinitely more interesting and tolerable than any other adventure game efforts of the same time (and if you're a seasoned adventure game who enjoys this sort of thing, you will find the puzzles above average), but overall I found the puzzle in Fate of Atlantis to veer too often into the territory of illogical and irritating, and it is not in the same league as the first two, and generally consistent, Monkey Island games. There are a lot of clever puzzles here, to be sure, and it's certainly a tremendous improvement over Last Crusade in regard to overall design philosophy (a classification it gets automatically for the absence of dead-end scenarios).

Like its predecessor, the game also jumbles things up a lot with enjoyable results (such as a lava crossing bit at the center of Atlantis, or the inclusion of a gear puzzle that's somehow not the loathsome waste of time that gear puzzles almost invariably are), and I appreciated how some puzzles are randomized on each playthrough, but it's definitely an adventure game that you'll want to play more for the story, the characters, and the overall experience rather than for the brainteasers, which often just feel like drawn out obstacles to your progress rather the fun challenges they can be at their best. The game's final section in Atlantis provides the height of puzzle frustration, in no small part due to the tedious backtracking involved. And, while Indiana Jones is a character who uses his smarts as much as his fist to move forward, you may find yourself asking why your have to engineer a makeshift torpedo with the MacGyver-level of ingenuity the game demands in one Path. A positive I can award on the subject is that as with Last Crusade, there are sometimes multiple ways out of situation depending on your inclination toward using your fists or your dream box (even within one of the three Paths), and the mixed quality of the puzzles detracts little from the overall experience.

Like its predecessor, Fate of Atlantis does its best to acknowledge the action side of Indiana Jones as best as possible within the parameters of a graphic adventure game. Arcade sequences include a Monte Carlo car chase, fez-spotting in a crowded market, camel/balloon desert travel, and submarine steering among others. These action bits are easily the most abused by the passage of time. I actually found them less successful than the kinetic segments of Last Crusade - the biplane sequence in that game, while pretty much impossible, is nonetheless fun, whereas Fate of Atlantis's offerings, while just as sparse and much simpler, suffer from dullness and tedium. Some of the ideas were probably ill-conceived, but I also partly blame SCUMM itself, which was infamously not versatile when it came to implementing gameplay that the engine wasn't strictly designed for. Then there's the most obvious of the game's action elements, the fistfighting, which was also carried over from Last Crusade. What was not carried over was the absurdly high difficulty.

Much as I feel schizophrenic for saying it, the fighting in Fate of Atlantis is too easy. While in Last Crusade it could be a trial to beat bad guys even if you'd mastered the controls, here you can win every time just by mashing the punch buttons – no strategy is ever required. And that's not taking into account the game's super sucker punch feature (an option documented in the manual itself rather than being the scandalous secret cheat some believe it to be) – pressing "0" on the numpad will make Indy take out his nemesis in one punch, giving those who are totally adverse to action a way to skip the dexterous stuff altogether. The feature is a good one, but it would have made a lot more sense if the fighting it allowed you to bypass were a bit more complicated. Heck, you can even opt to retreat from any fight once you reach the Nazi-infested Atlantis. In general, this is an adventure game that's at its best when it stays within its own territory; the occasions on which it tries to offer something different are well-meaning but often failed experiments.

While there are no dead-ends, Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis does resurrect one feature that other LEC games made after Last Crusade did not: the ability to die. (I'm not counting the drowning gag in Monkey Island 1.) In the case of Fate of Atlantis, I fully defend the inclusion of death scenes because it is true to the character's dangerous escapades, and the way it is executed it is very much an aesthetic choice rather than attempt to frustrate the player. The ways that Indy can die are fair and give the material stakes. Since the hairy spots Indy gets himself in can be seen coming and any sensible player of this genre would be saving with little reserve anyway, you can put me squarely on the side of the fence that supports the death scenarios in this particular game. I I should also mention the reprisal of the "Indy Quotient," which awards the player with a score of the IQ Points they've attained through creative puzzle solving. If you enjoyed this Sierra-like feature in the previous game, you'll like it just as much here; others won't even notice its existence.

The game's soundtrack, once again composed by the venerable triad of LEC composers (Michael Land, Peter McConnell, Clint Bajakian) is nothing short of excellent. Like every other aspect of the game, it's wholly original, but of the distinct flavor of its base material. Beyond the opening credits it doesn't reference John Williams' recognizable Raiders March to the degree one might expect, nor does it cheaply recycle specific themes from the trilogy (which is more than I can say for Kingdom of the Crystal Skull). And it doesn't need to, because the compositions here are strong. I can easily remember the game's main theme and Nazi theme, just as I can the counterparts of the original trilogy. Like with Monkey Island 2, the fact that the music is all MIDI doesn't make the effective use of iMUSE and the overall memorable and invaluable nature of the music any less impressive. I don't think I'm falling victim to hyperbole when I say that without its score present, this game would suffer more than a little - the game's most evocative moments are a collaboration between setting, subject and sound.

While Monkey Island 2 may have had Indy beat on the visual side of technological breakthroughs, Fate of Atlantis evens things out by being the first LucasArts game to offer a subsequently developed "Talkie" CD-ROM (complete with fully voiced dialog and digital sound effects) version in addition to the earlier floppy disk version. (The CD version of Loom was an externally developed anomaly). Unlike future Talkie releases, however, this game was not originally written with a vocal version in mind, and I think it shows in the dialog delivery, which doesn't always feel natural.

As an early effort, the voicework is solid, and given the state of the technology the voice actors did the best they could with what they had. The cast includes fan favorite Doug Lee as Indy, who would go on to voice the character in Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine. Hamming it up as head baddie Dr. Ubermann is recurring voice actor Nick Jameson, who would go on to play the likes of Max in Sam & Max Hit the Road and a number of other characters in future LucasArts adventure games, as well as Double Fine's Psychonauts. Overall the voice acting enhances the experience, though in the case of this game I recommend turning it on along with the subtitles, especially since there are actually some discrepancies between the spoken words and the written ones. While definitely a primitive effort, the spoken version of Fate of Atlantis was an auspicious start from a company that would become renowned for its bar setting voice work.

In my Last Crusade review, I suggested that while the traditional graphic adventure is not the obvious framework for an Indiana Jones game, the Indy games that belong to the genre are nonetheless the best entries by a long shot, with Fate of Atlantis occupying the throne. Although we're unlikely to see an Indy adventure game again, it's interesting to observe that Indy's story and character driven interactive outings have fared better than his passable but by no means spectacular Tomb Raider veined installments, or his more successful straightforward sidescrolling fare in Greatest Adventures. But heck, at least those were playable, which is more than you could say of most of the character's other video game exploits.

As was the strategy with Last Crusade, LucasArts released an externally developed "Action" version of Fate of Atlantis to accompany the graphic adventure, and the results were very similar to that of Last Crusade's companion piece: deplorable. Perhaps one day we'll get that ideally story-driven action/adventure Indiana Jones game but until then, we can always enjoy Indy's greatest gift to the medium to date, a position it's not likely to forfeit to an effort whose physics engine is touted as the primary selling point. The summary I can give Fate of Atlantis is this: exactly like playing through an Indy movie on your computer screen. That's the highest aspiration I can possibly imagine for a game based on a movie franchise.

"How can a game so old hold up so well?" is a question one might ask of any of these adventure games. I'll reiterate an explanation from my Monkey Island evaluations, which is that the things that don't get corrupted by time are the things Fate of Atlantis is most interested in, and are therefore what define it. Sure, it's not entirely possible to gloss over of the 1992 title's several outdated characteristics, but no antiquated attribute is fatal to it now, nor will it ever be. The fact that the expressive character animations are rendered with a low number of pixels, that the beautiful hand drawn backgrounds are of limited resolution, or that the engrossing soundtrack is orchestrated fully in MIDI hurt Fate of Atlantis about as much as the obvious matte paintings hurt Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Words by by Jason, who probably would have at least called somebody to go thaw out Dr. Heimdall. I mean, they just left him there.

Five out of five Murray skulls

Pros: Presentation is exemplary. Great story, characters, writing, art, atmosphere, music. Incredibly complex and lengthy thanks in no small part to the unique Three Paths feature. Voice acting enhances the game. The Indiana Jones game to beat.

Cons: Puzzle design falls squarely in the old-fashioned adventure puzzle vein and can be very frustrating. Arcade sequences offer variety but little fun. Fighting segments may be just as misguidedly easy as Last Crusade’s were misguidedly hard.