On the Nature of the Monkey Island Caribbean, the Structural Beauty of SCUMM Games, and the Eccentricities of Sierra.

I had an epiphany once, when I was playing The Secret of Monkey Island in one of queztone's Amsterdam hash bars. It all became clear. I knew what this holographic Caribbean really was.

Because we've all known for a long time that this ostensible world is not 'the 17th Century.' I mean, there's a vending machine and stuff. So we plunge into the belief that there's a secret to be found, and people connect all the Disney dots, and then, in the end, we stop thinking about it. But just for a moment there, I saw it as something else. It was a Sierra game.

Coming fall 1990, the only graphic adventure game that asks the question: what's sharper, your sword or your wit? Sierra On-Line presents Roberta Williams' Pirate Quest!

Remember the halcyon days of youth, of beige computers and floppy-disk drives; autumn Sundays and alternate realities? And above all else, the thrill of a new game coming from those matrimonial wizards, who eschewed the bright lights and certain fame of classy coastal towns to code instead alone and secret, deep in the mountains.

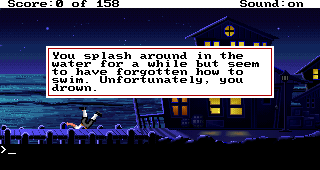

I remember it all so well. "My name's Guybrush Threepwood and I want to be a pirate!" It was an opening line that spoke volumes to me. I quizzed the lookout and he told me to go to the Scumm Bar, and The Quest had begun. As a true adventure gamer, weaned on the pitfalls of exploring dangerous worlds, I saved my game and ventured forth, my hand sweaty on the joystick as I guided Guybrush down to the Melee Island harbour and towards our destiny. The Scumm Bar: I could see it ahead – but in my excitement I slipped, my hand went astray, and I could only watch in dismay as Guybrush wandered off of the jetty and fell into the midnight ocean.

Jesus H. Christ, can you imagine? What a nightmare that would have been. And whilst that terrifying vision of a world without LucasArts might seem cruel and unusual on my part, please allow me to explain.

That is really the only frame of reference LucasArts had in 1987 – Sierra had created the graphic adventure game seven years prior and then used the genre as their own personal playground ever since. And to load up King's Quest, you could see the attraction – finally a visible world that you could explore at your own discretion, in your own way. The world was alive around you; on the very first screen there are alligators swimming back and forth in a moat and it is surely groundbreaking.

But there was also a problem. The Sierra problem, or: Roberta Williams' bizarre latent fetish for springing elaborate deaths upon people without warning. If you were generous you might say this is her commentary on our existential crisis, or perhaps just a parable-esque warning on the transient nature of life. Whatever the case, it's a troubling insight into a unique mind, and the single greatest problem of the pre-SCUMM graphic adventure game.

But was it a design choice? Sierra obviously had to write everything that happens, so presumably it was. Perhaps they were going for the truly open world, where sure, death was possible, but so was anything. You can go wherever you like within the realm, you can type whatever you feel and, if you're clever, the game will follow your commands. The assumption was that people would be sensible enough to try and guess what Sierra wanted them to type, and they would be rewarded by avoiding death.

I would often amuse myself joylessly when playing these games by poking holes in this assumption. "Admire the carpeting," I would type. The word 'admire' will not be needed in this game, it would reply. Thanks for suspending my disbelief, Sierra. Then I would get cocky. It's like the Mitch Hedberg joke about his desktop fan oscillating, and it looks like someone shaking their head – so he asks it questions. "Do you keep my documents in order?" But in my case I would be there typing "have fun" so I could get the momentary soulless pleasure of seeing the game state The word 'fun' will not be needed in this game.

The problem was always going to be the same, and that is; it's impossible to predict everything that people will type into the game. 'Admire' as a verb would be as useful in King's Quest as it would be in Maniac Mansion, which is to say it would have utterly no use at all. We can all 'admire' for ourselves, without the characters in the game having to join in as well. But the difference is, the Sierra games act as though you can do those things. Their assumption that the player will go along with them falls apart when it becomes clear that they're not playing fair – because if you can die by foolishly wandering into a pond, then it really would make sense if you could admire the fucking carpets as well.

Well here I am, I've wound up ragging on Sierra and that's not the point. They were essentially making graphical versions of text adventures, and the only way to play a text adventure is with a parser. They were forced to adapt that gameplay dynamic, and only a fool would say the addition of graphics was anything other than an improvement. Besides, even if they'd actually had the verb icon idea they wouldn't have been able to implement it: the technological restrictions were too limited back then. And this is supposed to be about LucasArts.

Maybe the real problem – and the one that only people as intelligent as Ron Gilbert had cottoned onto, back then – wasn't the deaths at all. It was the laziness of the gameplay mechanic. Think about it – there's one solution to every problem in any adventure game, LucasArts, Sierra, anyone. You find that solution and then the game progresses. Repeat until you reach the end. Everything else is there to throw you off the trail and add an element of challenge – the part that makes it a game, shall we say, rather than an interactive story.

Now it's easy to imagine how simple it would be to code the correct solution to a game – a sort of complex series of 'if x=true, then y=true' type scenarios. But how to integrate all that other stuff? Clearly, in Sierra's case, they didn't integrate it. They certainly made it look like they did, but they actually didn't. You go down the wrong avenue of pursuit in a Sierra game, and you better hope to God you've saved recently or you're screwed. It actually punishes you for being inquisitive.

And okay, this is not a new revelation; we know that Sierra games are bad because there are dead ends and that LucasArts games are good because there aren't, but isn't it worth reflecting on the sheer beauty of that? The Sierra games are coded like a straight line from A-to-B, and there are dozens of tangents coming away from that line but they all end in a game over. LucasArts adventure games have that core A-to-B structure too, and just as many tangents, but each and every one of those tangents somehow meander its way back to the main line. I mean Christ, there are no dead ends! Every move you take is a step forward, even if you're barking up the wrong tree – because you're being inquisitive, you're exploring, and even if you're wrong you can take something good from it because you know you can cross that potential solution off of your list.

So, wow. It was a nice epiphany and I'm sorry I bored you with this paean to SCUMM, but it is literally beautiful.

Wait a minute. Wasn't I saying something else, too? Ah yes, that's right – by dint of an extremely lazy and ill-conceived method I was trying to say that The Secret of Monkey Island is a Sierra game.

Did any of you ever play Police Quest? It was an interesting game because it actually expected you to act like a real police officer. I didn't realise that cops had to perform a 360-degree vehicle check every morning (duh) and so when I drove away, I got a flat tyre outside of the station. If that were LucasFilm Games' The Secret of The Death Angel, I'd probably be able to get out of the car and change the tyre, but not so in Police Quest with its grimly predictable 'game over'. But in a weird way, it was more annoying when I finally managed to get that first day at work under my belt and it was time to get changed and head home. There's a locker room, and I realise I have no idea which one of the lockers is mine – and then I further realise that the game isn't going to help me out because of the logic that... the character knows which locker it is.

The Secret of Monkey Island throws that kind of crap out from the opening line. Guybrush doesn't know shit, and that puts him and us on a level playing field. It's subtle and incredibly liberating.

I'll compare it to another scenario in Police Quest. Early in the game you pull over a sexy woman for running a red light, and she offers to do 'anything' to avoid getting a ticket. Now, you're in character – as a cop, no less – so you're supposed to just book her and follow the letter of the law. But, in another one of my humorous Sierra-deprecating moments, I typed in 'give me a blowjob' – and stone me if she didn't agree. One phone number later, she drives away and I reflect on a successful day at work. (In actual fact this decision causes a fracture in the game, and although you can keep playing – and saving – from this point, you can't actually 'win').

Guybrush has no such obligations. There's no reason why, if he was somehow in that scenario, requesting oral sex would be the wrong thing to do. Tim Schafer and Dave Grossman's placeholder dialogue reflects that. As it was never intended to be used in the final game, they wrote funny satirical lines that expressed the same basic sentiment (friendly, aggressive, etc.) as would be needed in the game proper. And the only thing this could be a satire of is a Sierra game.

Going to Meathook's house and insulting him to death about his baldness is the perfect example. You could see yourself typing similar insults in Pirate Quest – the difference is, in Monkey Island, you can get away with it. Not only is it possible to insult the guy, you can do it relentlessly and still convince him to join your crew. It's three guys from LucasArts making a game where you can say the ridiculous, out-of-character things you sometimes want to say when playing an adventure game and you understand that the real-life consequences of virtual indiscretions are nil.

This is why they're funny games. This is why they're enjoyable to play, rather than frustrating exercises in trial-and-error. This Caribbean that is presented to us in that first game is a simulacrum of every graphic adventure that came before. It's a self-conscious game, and it cares a lot more about how good of a time you're having than how true-to-life it is.

So a superfluous woo-hoo. After inexplicably trying to replay some Sierra classics, I realise just how much I love this bloody pirate game. It's even better than we generally give it credit for. Or maybe we did give it that much credit all along – and if so, well, it's just nice to find that when I actually think about it, it's completely deserved.

elTee

14th September, 2009.