Were logic driving the bus, the nineteen-year gap between the third and fourth Indiana Jones movies would have been exceptional. If a fifth installment was going to be produced, went sensible thinking, then surely it could only ever have a quicker turnaround. That’s before weighing the built-in ticking clock of Harrison Ford’s age, already an unprecedented integer for headlining a live action summer swashbuckler still aiming its punches at a competitive level. And yet, in the end, it took a comparable fifteen years for Indy’s final theatrical outing to arrive -- the accidental fulfillment of a five-film proposition made back in 1979. (Footnote: This trivia sometimes gets romanticized as intelligent design. The mundane reality: As part of the deal Paramount made with Lucasfilm to finance Raiders of the Lost Ark, the distributor wanted their rights to extend to any sequels in exchange for their many concessions to Lucas. Four was the somewhat arbitrary number that was arrived at, but there was of course no commitment to produce them.)

For all its worldwide adoration and box office boffo, Indiana Jones has consistently been relegated to second string at Lucasfilm, be it within the context of the film/television business or the interactive one. For decades now, the Lucas empire has seemed perfectly happy to maintain a ratio of something like 10:1 when it came to Star Wars and Indy, and a peek at the actual output – and I’m talking well before Disney ever came bidding – pretty much takes away the “seemed” part. What might have been considered the crown jewel of another company somehow ended up treated like a niche property by its single-minded rights holder.

Part of the explanation is that, at least as a movie series, Indiana Jones has been uniquely tied to the whims of a tiny set of controlling players. Rather than by studio fiat – the ordinary way blockbuster sequels get going – Indy installments have traditionally been initiated by George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Harrison Ford, serving together as a sort of custodianship, extending the series only if they could reach consensus among themselves. A combination of the triumvirate’s fitful interest and struggle to find common ground is the short version of the story behind Crystal Skull’s distended development.

Lucas, who considered himself the man responsible for coming up with each of the Indy plots, and was thus the party it fell on to get the ball rolling, did not make a fifth movie a priority in the immediate years after the fourth’s successful release. Disney didn’t see fit to rank it any higher on the agenda when they acquired Lucasfilm in 2012; making it clear that buying the studio was about Star Wars, the focus went, as it always did, exclusively toward a galaxy far, far away. The attractiveness of Indy couldn’t have been enhanced by the comparatively challenging nature of it as a creative proposition (Indy is very much about a specific character and his period rather than a universe, making it less open-ended than Star Wars), nor by the fact that the Mouse had to drop a sack of money on Paramount to even get the distribution rights for a new movie in hand.

Finally, in 2016, Indiana Jones 5 was officially announced, with Steven Spielberg signed on to direct a story concocted with his go-to tentpole scribe, David Koepp; Lucas was nowhere in sight. After four years of supposed development, Spielberg couldn’t manage to arrive at material he was motivated to shoot, and it’s difficult to shake the impression that his heart wasn’t really in the thing. It was a suspicion the results of Crystal Skull (also drafted, in the form shot, anyway, by Koepp) had led him to be accused of in 2008, and perhaps in the end he came to the conclusion himself. And so, in early 2020, with his star now in his late seventies, Spielberg abdicated the director’s chair, inviting James Mangold (Logan, Ford v. Ferrari) to pitch his own take on a finale. The filmmaker’s outline met with approval, and off Mangold went for a year or so to prepare a script with his usual writing partners (brothers Jez and John-Henry Butterworth), clearing a path for the project to finally go before cameras in the summer of 2021.

In other words, once Lucas and Spielberg let go, the project magically entered a normal development process. One that, while not especially rushed, notably doesn’t seem to have gone through any particular drama, interference, or laming by committee. (Footnote: He said, daring an eventual tell-all to expose him as a naïve idiot.)

It was background that was difficult to banish from my mind when it turned out that Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny was a damn good movie, a realization I began to trust pretty early into watching it. There’s an infectious enthusiasm behind the picture that simply wasn’t detectable last go round. It’s the difference between a movie made to satisfy checkboxes and a movie made to satisfy. It’s not that Mangold and his team went wildly off the reservation or showed anything less than reverence to the traditions of the series as they rightly tried to push it into some new territory. It’s just that it feels they were left to balance those requirements, as part of the job.

Crystal Skull wasn’t subjected to a single molecule of external meddling, but its creative authorities operated as their own micromanagers, and the shooting script that resulted – with its workmanlike, low-voltage, patchwork quality – can hardly be separated from the process that produced it. (As documented, that process reads like reluctant horse-trading between the stakeholders more than an impassioned creative endeavor, dragging on in the name of priorities so misjudged as to make collateral damage out of superior executions.) Sure, it would have been nice had Lucas and Spielberg closed out their creation shoulder-to-shoulder with Ford, but if they were less than gung-ho about landing the plane themselves, then in a bittersweet way they did right by it in passing the task to a cohort that was. Forcing themselves into the cockpit out of some weird sense of obligation is how you wind up with something no one is particularly jazzed about.

Dial of Destiny opens as tradition dictates (minus a Paramount mountain dissolve gag), plunging us into a somewhat self-contained teaser, already in motion. Like Last Crusade’s, this prologue is a flashback: In 1944 Germany, a mid-forties Indy (Harrison Ford, digitally de-aged about a decade beneath that in a showcase of emerging technology) is teamed up with British ally Basil Shaw (Toby Jones) to infiltrate a castle from which stolen artifacts are being evacuated. Their objective is to recover the Lance of Longinus, but this toe dip into the internet-approved pool of Judeo-Christian holies is a red herring, and soon the Allied archeologists stumble upon the titular dial that drives the story. It represents one half of the Antikythera, a device of Ancient Greek origins believed capable of predicting “fissures in time” – essentially, an Indy-fied version of the map in Time Bandits. (Closely resembling an astrolabe, the fictional whatsit draws inspiration from inventions attributed to Archimedes, but curiously, without any hijacked Greek mythology giving it a claim on the supernatural. The movie kicks Athena and Zeus to the curb to go all in on The Power of Math.) For Indy, liberating historical treasures and punching out Nazis is all the motivation he requires, but Basil is fated to become possessed by the dial’s supposed powers – a true believer. So too is Jürgen Voller (Mads Mikkelsen, transparently having a ball behind understated choices), a nerdy Nazi scientist whose physical ineffectualness is answered by a shouty colonel (Thomas Kretschmann) unbashful about getting his hands dirty.

While it establishes the villain and the McGuffin, the raison d’etre of this twenty-five-minute set piece is to serve up the criterion example – a reminder – of the adventures Indy got up to in his heyday. Even the soundtrack is a shameless medley of cues from the previous flicks. Indy’s escape from the fortress and ensuing chase for his prize (taking place on foot, motorcycle, and train, with a runaway-anti-aircraft-machine-gun-shaped kitchen sink thrown in free of charge) is so stuffed with gags that it could be a trailer cut together from the climaxes of ten wartime Indy flicks. While on some basic level it will never feel correct to me for an Indy movie to be so dependent on digital effects, the fact is that battle was lost a long time ago. If you go in prepared to give yourself over, the opening sequence rewards you with a ride, one that is at least grounded in location shooting and physical sets to help you wash down some rubbery artifice. (The nighttime setting may be a gesture to the post houses.) And it can’t help but serve as a somewhat bitter reminder of all the World War II adventures we ought to have gotten in the 1990s, during one of the series’ long dormant periods.

Dial smash cuts from this reintroduction to 1969, where the balance of the story takes place. The contrast is deliberately disorienting: We meet “present day” Indy at the age of 70, on the morning of his imposed retirement from Hunter College in New York, awoken in an ignoble state in his Manhattan apartment. It’s a rude adjustment that nevertheless allows that Bogart-y aspect of Indy as a weary boozer to make an appearance after a disappointing hiatus. (I’m pretty sure the only thing we saw Indy sip from last time was a mug of coffee, in what was on the whole a tweedier take on the professor’s tenured years.) His retirement coincides with the Apollo 11 Parade, hammering home how out of place this hero of the pulp era looks in the Space Age, where a last subway ride to the university crams the hangdog professor next to youths cos-playing as astronauts.

To accommodate the age of its lead, Crystal Skull brought the series to the Cold War period, and of course we’re only further into it here, with a national gaze toward the stars underlining the outmodedness of the two-fisted archeologist’s earthbound exploits. In fact, Dial does its immediate predecessor a little bit of a favor by swinging at some of what it had teed up: Skull made noises about dozens of wartime missions Indy performed in the interim since the trilogy (Dial’s teaser lets us see one), and the decaying relationship between Indy and his government that it established with rather outsized emphasis (considering nothing came of it) is exacerbated here. Indy is expected to swallow seeing his old nemesis Voller, rebranded as Alabamian physicist “Dr. Schmidt” in a wink to Wernher von Braun, recruited by NASA for his preeminence in rocket science. It’s the closest any movie in this series gets to commentary that this unethically-sourced knowledge was instrumental to the success of the moon landing program presently being celebrated.

Voller/Schmidt is, of course, no reformed Nazi, nor does he let the fact that Washington selected themselves as his benefactor go to waste. Emboldened by a position that washes his past and sponsors his whims, the starched and resourced uber-weirdo is about to make good on a scheme he’d been dreaming of since the Axis defeat: reassemble the Antikythera, use its rewind feature to patch up the Führer’s victory-forfeiting lapses in strategy, and restore the Third Reich. I mean, what else was a character with that LinkedIn profile likely to be up to in this movie? But as the series’ last bespectacled Nazi might put it, there are other interested parties. Helena Shaw (Phoebe Waller-Bridge, playing a comic mercenary in the Preston Sturges vein), the thirty-something daughter of Basil and Indy’s on-paper goddaughter, gets to Jones first, working the feelings of twilight uselessness he’s moping in to get him to take her to the dial, which Indy has interred since the war in an archive that resembles a gigantic evidence room. She then double-crosses him to buy herself time to evade Voller’s goons, already in pursuit of her, and hawk the relic on the international black market.

Indy is left to furnish his own escape from Voller’s new generation of henchmen (an assortment of good old boys led by the scenery-chewing Boyd Holbrook and the gigantic Olivier Richters, a double-act variation on the old Pat Roach heavies), leading into another lively set piece amidst the ongoing parade that gallops through the streets, and then the subways, of Manhattan. (Among the lunar-themed floats is one hauling a boulder-like papier-mâché moon, and you almost wish Mangold showed a little less judgment and took the bait.) Some dead bodies along the way fit Indy for a murder frame, pulling him into the mess and one last adventure. Straddling between observer and participant in this mayhem is Agent Mason (Shaunette Renée Wilson), a CIA operative indulging Voller’s shenanigans who serves the minimal but pointed function as a kind of avatar for a country easily misled in its opportunism -- the movie argues that Indy’s disillusionment isn’t wholly unearned. The particulars of the story past the first act are best left to experience as intended, but know that the Zelda-like quest for the missing half of the Antikythera (with plenty more hot potato played with the one already in the mix) leaves the U.S. in short order, taking Indy and the signature red line to the streets of Tangier, the harbors of Athens, the bottom of the Aegean, the ruins of Syracuse, the secret chambers of treacherous caverns, and some destinations altogether more…exotic.

Indy movies don’t usually wear much in the way of baggage handed to them by their predecessors, and anyway for all its weaknesses Skull didn’t saddle a follow-up with onerous details to address: In the final tally, Indy got married to Marion (Karen Allen) and was presented with the son (Shia LaBeouf) they had together. In Dial, the wedding ring remains on Indy’s finger – how Marion might figure into the story beyond that shouldn’t come from me – while Mutt’s absence is explained away with a line of dialog. (Considering that audience favorite Henry Sr. was written out last time with a production photograph of Sean Connery on Indy’s desk, I have a hard time believing anyone will object to Mutt being dispensed with in this no-less-perfunctory manner.) While this light housekeeping frees Dial to be a fairly self-contained installment from a story perspective, there’s an understandable degree of vocal awareness of the previous movies given its position as a finale (making it the second film, after Crusade, to be designed as such).

While Skull’s attempts to balance the old and the new just come off as hedging, Dial finds more success by looking at the challenges inherent to a story about an elderly Indy as opportunities to seize and relish rather than business it’s obligated to transact. Skull may not have retreated from Indy’s age, but neither did it do much to embrace it. Like most of its ideas (the villain’s psychic capacities, the Red Scare backdrop, the cheap inclination to merge all the protagonists’ backstories), it was flirtation without follow through.

When “surface-level” is used as an accusation against movies like these, it is understood that we’re speaking in relative terms. Even within a series where stopping for a breath is treated as a borderline impropriety, the self-disinterest on display last time around was truly exceptional. The entire supporting cast was reduced to functionaries, assassinating any capacity for pathos -- How can we share Mutt’s weepy reactions to his father figure’s mental state when we never knew the guy when he was sane? How can we be affected by Mac’s treachery when it’s the only attribute of him that’s ever defined? How meaningful can Marion’s return be to us when the entire wad the movie has to blow on the character is her reveal? -- while Dial finds reward in mining the potentialities of its own ideas past lip service. As with the trilogy, Dial manages moments of poignancy, and though the movie isn’t totally above pandering (Indy gets a pep talk from Sallah in a welcome cameo), those indulgences aren’t used as substitutions. As for going back to the Nazi well: It’s at least a new angle on it, and it might feel lazier if it didn’t also feel uncomfortably current.

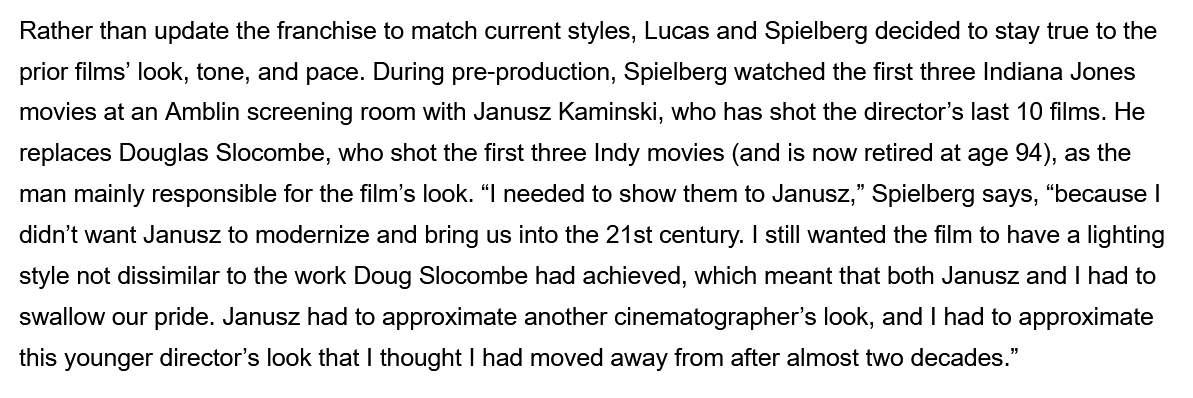

Film stock having long been abandoned by mainstream productions except those under directors in a privileged enough position (Scorsese, Tarantino, PTA, Nolan, Gerwig) to flaunt vanity-based expenses, Dial of Destiny is the first Indy movie to be shot digitally - set photos suggest an Arri Alexa LF - but the results prove that the tastes of the cinematographer (Phedon Papamichael, a veteran Mangold accomplice) are far more influential to the final aesthetic than the acquisition medium. Spielberg shot Crystal Skull on 35mm, but this did nothing to make it look “old school” or even vaguely kindred to the trilogy that Douglas Slocombe set the style for. Whether the reasons were ego (Janusz Kaminski’s usual filtration, aggressively unmotivated lighting, and decidedly un-vibrant (Footnote: Being the only part that was adjustable, the color grading did receive a beneficial de-chlorination when Crystal Skull was remastered for 4K, but the elementally smeary, Sky Captain-like vision was attained on set and cannot be redeemed with knob-turning.) palette preferences feel fatally self-conscious in an Indy context), a genuine misapprehension of the objective, second-hand consequences of the sheer volume of the CGI sprung for, or some combination of the three doesn’t much matter; if the intention was to honor the look of the earlier films, it was an unqualified failure, no matter how oblivious the perpetrators might have somehow been to that:

Don’t get me wrong: Dial very much looks like a 2023 release, and to be sure digital augmentation abounds. Much could be observed about the ways it too stands apart from the 80s pictures. But gone is the distancing, jeopardy-banishing pane of halo’d gauziness that the last outing encased itself behind. “Realistic” is the wrong word for what the Indiana Jones movies looked like as lensed by Slocombe, but they certainly had a tactile, earthy, three-dimensional quality which depicted a world in which gravity could be said to exist. On the other hand, if you told me that Skull was shot exclusively in front of green screens during a solar flare, I would have no follow-up questions. Dial didn’t need to invest in some monkish commitment to looking and feeling like a throwback movie in order to correct that error, which had nothing to do with “modernity” and was just distractingly off-point, full stop.

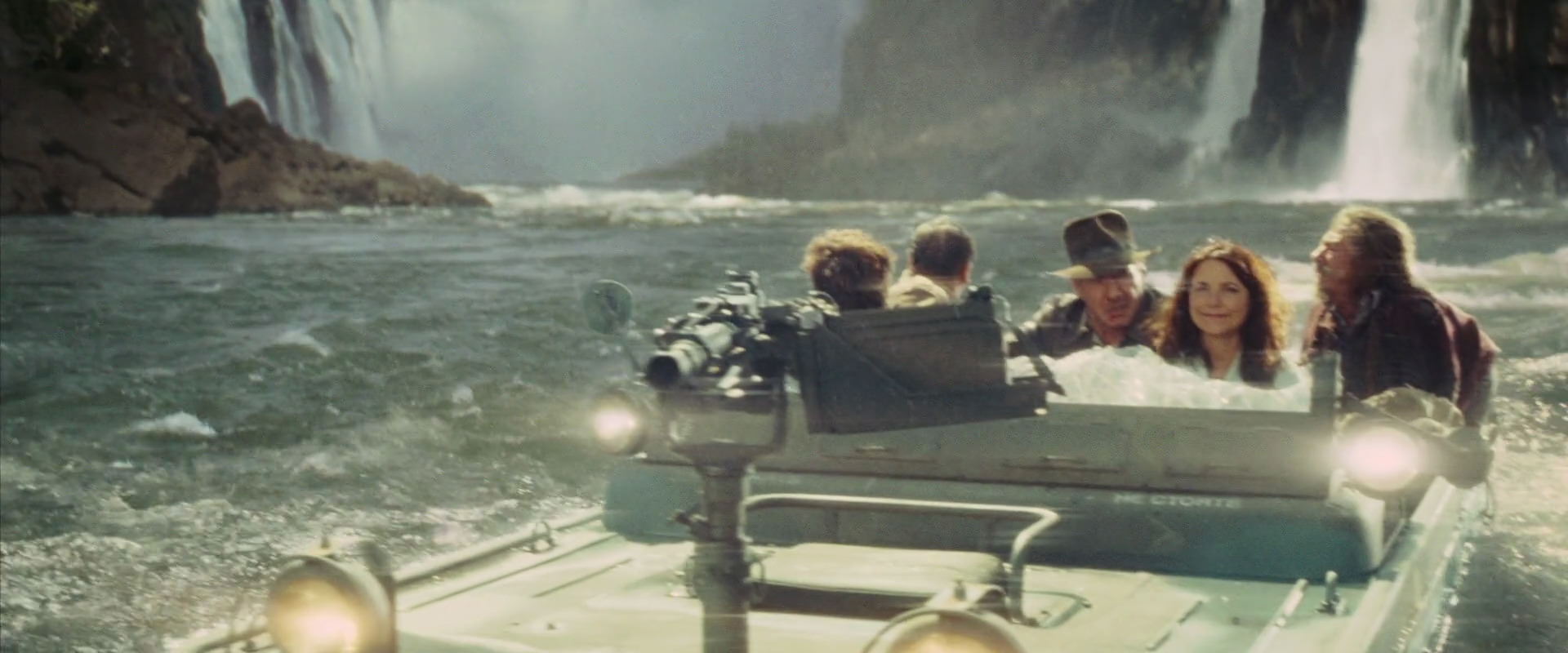

Supporting Papamichael’s work is a return to appreciable location shooting and a continued value placed on physical sets. (The production designer, Adam Stockhausen, happens to have recent Spielberg credits – he worked on Ready Player One and West Side Story.) While Skull’s sets (Guy Hendrix Dyas) were outstanding, they weren’t done the justice of being properly supplemented. Principal photography never ventured beyond the United States, leaving the entirety of the movie’s vision of South America to be simulated by Hollywood carpenters and ILM – and that’s for damned sure what it looked like, too. Even when the production made an effort to do stuff for real (the rainforest chase was shot on private land in Hawaii, with oodles of traditional stunt and vehicle work involved), every measure possible was taken to visually compromise the sense of tangibility all that sweat is meant to earn. If the whole thing ends up looking like a cutscene, does it even matter that there’s a bunch of practical work hypothetically drowning somewhere beneath the pixels, arbitrary diffusion, fabricated smoke, habitual lens flares and blown highlights? Whether at the outset or along the way, the point got lost -- Spielberg may not have shot Crystal Skull on a virtual stage, but much like his decision not to abandon Kodak, the aggregate result of all the choices he made or approved was that he might as well have.

Pictured above: A movie shot on motion picture film. To what end, exactly? (Source)

In contrast with the U.S.-based Skull, Dial’s production headquartered itself in the UK (like the first three movies), with its stage work being done at Pinewood Studios. More to the point, the first unit didn’t sequester themselves there, traveling to the likes of Scotland, Italy and Morocco for important exteriors -- the sort of continent-spanning that is supposed to go without saying for any large-scale, period adventure piece. One of the basic come-ons of the Indiana Jones movies is their globe-trotting promise, and what audiences got for their admission last time was rendered foliage and background plates; the most effective location work in Skull was a train platform in Essex, Connecticut. Here again, Dial is a rebound, proving that being the product of a digital era was no excuse for the 2008 release to sacrifice a principle as elemental as it was implicit. Shot during a period of COVID restrictions, it couldn’t have been an inexpensive principle for Dial to reclaim, but the justification is on the screen.

It’s to be stressed that these efforts aren’t nice-to-haves or mere scorekeeping bona fides. The stage-bound, heavy-handed artificiality of Skull had casualties beyond neutered visual appeal. It meant that the movie was denied its best weapon for living up to the sense of grandeur that the earlier entries, for all their theme park ride priorities, possessed at least in moments. Raiders had it in some of the David Lean-ian iconography of its desert scenes, and in the general sense of awe it was able to whip up around the Ark of the Covenant; Temple had it in the trekking footage shot in Sri Lanka; Crusade had it when the heroes arrived at Petra, drafted to serve as the Grail Temple exterior. These are small moments, but those are the ones that sell illusions.

Its storyline certainly offered Skull the opportunity to follow suit, but we never get a sense of Peru that transcends interpretation by backlot and hard drive. The opening images of the theatrical trailer establish the Amazon more evocatively than anything in the actual movie. (It turns out that footage was just part of a second unit harvest to feed all the digital collaging later; the story’s principal setting was cheerfully deferred to post.) For Skull’s devoutly incurious purposes, the Nazca Lines are just another set extension, the discovery of a lost city another call time at Downey Studios, communicating zilch of the eerie splendor it should have been lousy with. It’s one thing to have Tunisia standing in for Egypt; it’s another to have Los Angeles standing in for everything. Like so many elements (imagine the possibilities of that jungle cutter or the uncontacted tribe, conceived merely as “trailer moments”), this drag’n drop South America is an unseemly waste that’s all the more distracting because we can easily guess at how Spielberg, who once authored the standard for this stuff, might have approached the opportunity in a hungrier frame of mind. A nuttily-bad Indiana Jones movie may be less objectionable than an indifferent one. What Skull leaves on the table creates the deflating impression that, had the director shot Raiders in the 21st century, he’d have just blown up the Flying Wing before doing anything in particular with it.

Any single frame of Aguirre, the Wrath of God ($370,000) depicts an Amazon that is more filmic, perilous, believable, evocative, and immediate than Crystal Skull’s ($185,000,000) shiny parody of it, one stitched together in post from composited elements and seemingly filmed through cheese cloth in what the radically charitable will call “stylization” and what others may speculate is what the Nazis saw when they peered into the ark. (Sources: Image One, Image Two)

Since Spielberg can shoot a movie in his sleep and has access to all the toys, Crystal Skull is still a clinic in surehanded composition and slick camerawork, but its effectiveness outside of academic appreciation is where it falls short, and Indy movies are not meant to be academic pleasures, but actual ones. The staging in Skull is so perfectly, damningly competent (well, the demise of Ray Winstone notwithstanding), with a cherished reprisal of comprehensible geography in the action sequences and a willingness to let things play out in a master (traditions long dispensed with even by 2008), but without any of the zip, crackle and involvement we associate with these movies. There’s a floaty, detached, inconsequential quality to the whole thing, like the director is fulfilling a prescription, and the phony vistas working in sabotaging tandem with the focus-buzzed photography hardly counteract the manufactured feeling. Again, the script isn’t of any particular help here – with its pacing issues, intolerance for buildup and lack even of decent transitions, scenes just sort of lawfully follow one after another – but Spielberg doesn’t show any availability for compensating, and anyway it’s inappropriate to treat his role as independent of the writing process.

And so it always comes back to that. The cast and crew are all showing up for work in Crystal Skull; the people who played hooky were the ones who were supposed to deliver ahead of the start date, and because that work is foundational, any compromises it’s greenlit with come out in the wash. The upshot for Skull was a bafflingly subdued energy, an inability to ever quite break out of first gear, and that’s lethal for a high adventure movie, which should at least have the ambition to astonish. Serving as a comeback on all fronts, Dial has fire in its belly and a sense of momentum, and you can surmise it’s for the simple reason that it was designed by people who were pumped up by the possibilities, and the prospect of sharing them. We’re not talking about splitting the atom here, but a basic ability to make good. I’ll put it this way: it was a moment of note when Indy fired his gun, because we’ve fallen to the point where that was in question. It seems that as an impressionist, Mangold does a more convincing Steven Spielberg than Steven Spielberg does.

John Williams joins Harrison Ford as the only other key player to show up for all five movies (Michael Kahn and Ben Burtt didn’t rate a phone call?), and he too goes the whole distance. While his score for Skull was perhaps overlooked, the bits of unjustified recycling were an unfortunate contributor to the general impression of a revival that couldn’t entirely be bothered. (The music heard during the obelisk scene is indistinguishable from the cue in War of the Worlds when the tripods emerge, while the composer’s reprise of the Grail Theme during the movie’s regrettable “What have we learned?” wrap-up was typical of a sequel far too prepared to outsource to your fond memories what it couldn’t arrange itself.) Here Williams is an extension of Dial’s return to form -- the story goes that the composer’s original plan to develop a few themes before passing the baton to someone else fell by the wayside once he got into it. Like everyone else, he vibed with what he was seeing, was excited to be there. Because the project had the goods at its core, everything was lifted around it.

I haven’t touched on Harrison Ford’s performance, because it was one of the few things I didn’t go in doubting. I’ve always felt that an Old Indy story could work marvelously, but like audiences, the actor had to wait for filmmakers who were up to the task of cracking it. Ford’s public indifference is legendary, but the affection he has for this particular character is obvious; if in the end he was the major force among the original team who pushed for this project in the face of all that impassivity, he was a good steward. And yes, he’s engaged on screen as well, where he also remains in great physical form, somehow. His commitment is total, the punches still thrown vigorously (and not without expensive consequences), the double-takes as gargantuan as ever. He sells everything he’s handed, and he’s occasionally handed some sensitive stuff -- whatever cheerleading the orchestra might be doing behind it, the power of the movie’s emotional crescendo is at bottom a solo assignment, and it underlines an inseparability between this actor and this character. Whether Disney will suffer to learn that lesson is a question for the future. Send me a postcard.

There will always be those who contend that the characters riding off into the sunset at the end of Last Crusade was the perfect conclusion to what will remain a trilogy in their minds. But whatever one’s thoughts on Skull, which was in the end simply a bummer of wasted potential rather than anything meriting the kind of rancor the web is apparently designed to channel, it was definitely not a closing chapter. There was room for a more conscious finale, and what we’ve got on our hands is proof that Ford was right to be stubborn in pursuit of it, and that those surrounding him were right to go along. If Skull was a gutter ball, Dial picks up the spare, and you’ll be glad they took the (after all, low-risk) gamble of trying to retrieve a fitting send-off. “Fly yes, land no” may describe a deficiency of Indiana Jones, but fortunately no longer of Indiana Jones.

Five is a good number for the series, and even though integrity probably has little to do with why that’s the grand total that forty-two years have racked up, there’s something to the idea, in a time where gross overinflation of franchises is standard procedure, that Indiana Jones remains a little more special for having been so bogglingly underprinted. And though Lucas and Spielberg sidelined themselves for the closing entry, they still appear as Executive Producers (as an advisor to Mangold, Spielberg’s title was a little more than sinecure, while Lucas asked to have his name included after being screened a cut), joining Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy in the credits, preserving a continuity reaching all the way back to Raiders. So in a sense, Dial of Destiny does represent the original team rounding off what they birthed, and fedoras are off to them for it being brought off as well as this, whether by their own hands or hands to which they wisely deferred. It was indeed a long way to Delhi, but a way was found of hanging up the bullwhip that leaves Dr. Jones with dignity and his audience with satisfaction.

Reviewed by Jason, whose first draft is currently being used to flatten steel.