Articles

LucasArts' Secret History #7: Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis History and Myth: X Marks the Spot

History and Myth

What amazes me about the Atlantis story is that so many people seem to take it as literally true. In The Republic, Plato relates his vision of a perfect city-state in an attempt to describe what justice is. One part of this society is the inclusion of a myth that would be told to the city’s people until they really believed it – that everyone was grown in the earth, but were created out of different metals. Some were bronze, who would accept their place as the workers; others silver, who would be the law-enforcement; and a few were gold, who would become the ruling philosopher class of Guardians. "Obviously its pure moon-shine," says Socrates to Glaucon, "but it should serve to increase people’s loyalty to the state and to each other."

Though Plato (via Socrates) bans all types of art from his perfect state, on the charge that they distract people from pure, solid truth (such as philosophy and mathematics), he's not against using myth to make a point himself. The myth of the metals is such a useful myth; so too is Atlantis. What point Plato wanted to make with Atlantis has since been lost, but it’s unlikely that he was merely telling a good story; even more unlikely that he was basing it on fact. Plato was a philosopher, not a historian. He pursued truth and not fact.

Atlantis nevertheless captures, binds and blindfolds the imagination. Atlantis is the hottest date you will ever have. Atlantis is the creak of the cupboard hinge as you reach in for another jar of honey. The idea of a lost civilisation is as old as Hal Barwood (approximately 21,000 years old), but Plato gives the most detailed and well written version. And The Fate of Atlantis is, I think, the best story based on this story. Plato would have banned it from his Republic, no doubt, but he would have done so with a rueful sigh.

The following article was written by Chris Ratcliff from LucasFiction, and gives more detail to everything I just farted out above.

- "Gabez"

The Lost Dialogue of Plato

Yes, Plato really did invent the story of Atlantis. Certainly, it is in his philosophical writings that Atlantis first appears. In one of his Socratic dialogues, Socrates has gathered with three fellow Greeks (Timaeus, Critias and Hermocrates) to discuss philosophy.

(In a side note, seemingly all of these are real people - Socrates was Plato's mentor, Critias Plato's maternal great-grandfather and Hermocrates a Syracusan statesman and soldier. There is no historical record for Timaeus, but he seems to have been based on Archytas of Tarentum, a philosopher and statesman whom Plato once met.)

Socrates is troubled. In previous dialogues he has described a perfect Society. But he feels his descriptions lack reality, a reality he has called upon his friends to provide. In particular, Socrates is troubled by the theoretical nature of his society, and would like to see it in action.

So Critias tells a story. It is a story he heard from Solon, his great-grandfather. Solon went to Egypt, where a very old priest tells him a story now old and barely remembered. Nine thousand years ago, there WAS a perfect society. "For before the greatest of all destructions by water, the city that was now Athens was preeminent in war and conspicuously the best governed in every way, its achievements and constitution being the finest of any in the world of which we have heard tell."

Yes, Athens was once perfect, and the Egyptian priest goes on to give a brief outline of the laws and regulations of that ancient city. Under these laws, the people of Athens "excelled all men in every kind of accomplishment." But one accomplishment rated above all else, truly confirming the greatness of Athens: says the old priest, "Our records tell how your city checked a great power which arrogantly advanced from its base in the Atlantic to attack the cities of Europe and Asia." What was this power? "On this island of Atlantis had arisen a powerful and remarkable dynasty of kings." This dynasty of kings ruled "the whole island, and many over islands as well and parts of the continent; in addition it controlled, within the state, Libya up to the borders of Egypt and Europe as far as Tyrrhenia (ie Italy)." Being a warmongering nation, Atlantis attacked Athens. And the true majesty of the Grecian capital was at last revealed: "Her bravery and military skill were outstanding... forced to fight alone, after running into direst peril, she overcame the invaders and celebrated a victory." But more was to come. Following the rout of the Atlanteans, "there were earthquakes and floods of extraordinary violence, and in a single dreadful day and night all your fighting men were swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis was similarly swallowed up by the sea and vanished." Atlantis was no more.

This is the story briefly outlined by Critias, and his intentions are pretty clear - going through the story in greater detail, we will get a chance to see Socrates' ideal society (Athens) in action, in peacetime and in war. But before Critias can expand on it, Socrates sets Timaeus a task - a full scientific explanation of the origin and evolution of the universe and man. Not surprisingly, this takes a while, and so the book in which we first encounter Atlantis is called Timaeus. For Plato structured his dialogue into three books, each identified by their keynote speaker - first Timaeus, then Critias, and finally Hermocrates.

Eventually Timaeus finishes his account, and Critias takes up the challenge, tracing the course of a mighty war between Athens and Atlantis. In those days, "Atlantis was an island larger than Libya and Asia put together".

Critias starts with a description of historical Athens. It is indeed a pre-scientific paradise. He moves to an account of the origin of Atlantis, and it becomes clear we are dealing with a myth of the Fall.

In the beginning, Atlantis was an island populated by gods and divine beings, and watched over by Poseidon. A dynasty of kings was established, and all seemed to be well. Atlantis had many precious metals, wealth beyond compare, plentiful supply of timber, and many animals, among them "numerous elephants." At first look, Atlantis seems to be an even better place than Athens.

After describing the origin of Atlantis, Critias moves to a description of the main city. It has a circular layout, divided into three sections by wide canals that ring the city. If that sounds similar to the Atlantis in Fate of Atlantis, well that's not coincidental. The basic design of the city fleshed out by Hal Barwood and Noah Falstein is given here, by Critias.

Now Critias tells us about the remainder of the island. This section, and much of what follows, didn't make it into Fate of Atlantis. Critias describes the military structure, politics and legal authority of Atlantis.

There follows a section called 'Degeneration and Punishment', and it is easily the most fascinating part of Critias. For many generations following the creation of Atlantis, all was well. The Atlanteans "retained a certain greatness of mind... and did not let their high standard of living intoxicate them or make them lose self control."

It didn't last. As Critias recounts, "the divine element in them became weakened by frequent admixture with mortal stock, and their human traits became predominant." The Atlanteans became human, and humans are fallible.

The Atlanteans themselves didn't notice anything wrong. "...they seemed, in their pursuit of unbridled ambition and power, to be at the height of their fame and fortune." The Gods, however, saw things differently. Zeus "decided to punish them and reduce them to order by discipline." He summoned all the gods together, "and when they had assembled addressed them as follows..."

But there Critias falls silent, his dialogue forever half finished. There is no more, and of Hermocrates there is no record at all. Nevertheless, the general outline of the myth is clear, and it is a most potent one. (For a modern retelling, see J.R.R. Tolkien's myth of Númenor, which contains a surprising number of parallels). It is these few paragraphs that have remained in the popular imagination, the Fall of the Atlanteans an Icaruslike case of flying too high, or delving too deep, awakening the Balrog. But in actual fact we don't know what Zeus's punishment was to be. It might have been the earthquake that sunk Atlantis, but there's no record of the time. Indeed the whole account seems to have taken place before Atlantis ever went to war with Athens.

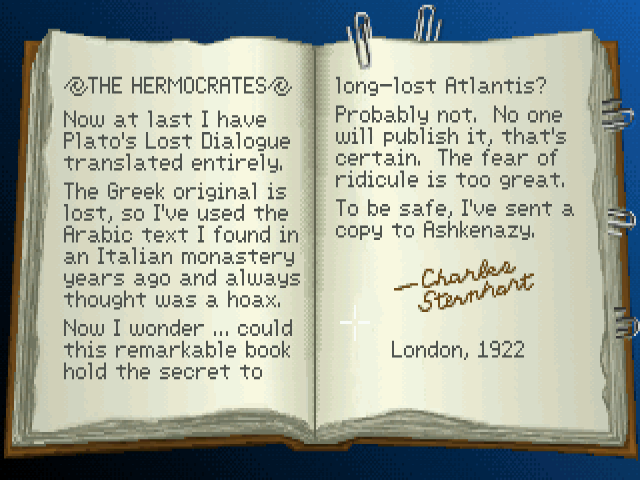

Which leaves us with just one question: what was Hermocrates going to talk about? Plato leaves us no clue, beyond Critias looking forward to Hermocrates' talk later that night. Here, at last, we have it: the Hermocrates is the Lost Dialogue of Plato. There's no evidence Plato ever wrote the book (in fact, there's some evidence to the contrary), but, muse Barwood and Falstein, what if he did?

The thought is probably not new to them. Atlantis is a popular subject. Thousands (or even tens of thousands) of books have been written about Atlantis. Most of those have probably noted the non-existence of Hermocrates; some may have found this mysterious; and a few would have speculated on its existence. Thus a new myth was born, springing from the old myth: the Lost Dialogue of Plato. When Indy snorts, "Another fine myth. That book is a legendary hoax," he's probably not wrong.

(As another side note, one of the game's puzzles involves finding out the title of the Lost Dialogue. This makes sense for your average lounge lizard, but Indiana Jones and Sophia Hapgood are supposed to be top-notch archaeologists, and would certainly know the names of the three books. Even if Indy didn't know it, Sophia definitely would).

Interestingly, the manual for Fate of Atlantis comes with its own bibliography. In addition to Plato, Falstein and Barwood list these sources:

De Camp, L. Sprague. <em>Lost Continents</em><br />

Donnelly, Ignatius. <em>Atlantis: the Antediluvian World</em><br />

Muck, Otto. <em>The Secret of Atlantis</em><br />

Grunwald, Henry Anatole. <em>Mystic Places</em><br />

Pellegrino, Charles. <em>Unearthing Atlantis: an Archaeological Odyssey</em><br />Vitaliano, Dorothy B. <em>Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins</em>

Of these, the Donnelly is probably the most infamous. First published in 1882, it pretty much takes as fact Plato's account. End side note.)

Back to the Lost Dialogue. Falstein and Barwood use it intelligently to set a structure to Indy's quest, forcing him to find Sunstones, Moonstones and Worldstones, plus a short retelling of the Fall of Atlantis. The text is certainly an invention of theirs, but it does mention specific objects that have been drawn from wider sources. For example:

The Tenfold Error

Hermocrates starts by correcting an error of Critias: apparently when translating from the Egyptian, a tenfold error was introduced. But Hermocrates isn't sure which way. Either Atlantis held sway 100,000 years ago, or 1000. At first glance this seems to be an invention of Falstein and Barwood, a neat way of allowing Atlantis to be put in the Mediterranean, instead of the Atlantic. But in fact the tenfold error idea has cropped up in learned journals. Apparently Plato had little idea of time and dating, and a misunderstand of the original figures might well have led to multiplication by ten, as the Lost Dialogue states.

Colonies and Outposts

Next, Hermocrates tells how Atlantis founded two colonies, a Lesser and a Greater, and how entrance these colonies and Atlantis proper required three circular stones: a Sunstone, Moonstone and Worldstone. This idea is probably an invention of Barwood and Falstein (but having not read each and every Atlantis book ever printed, it's impossible to be sure).

The idea of Atlantis establishing colonies, however, is a staple in the genre. After all, Atlantis was a mighty empire, conquering lands far and wide. How are you going to rule over distant countries? By establishing Atlantean colonies. Thus Iceland, South America, North America, Africa, Egypt, and in fact just about anywhere is a candidate for an Atlantean colony. Interestingly, one of the colonies you get to visit in Fate of Atlantis is in Algeria, which Plato tells us Atlantis definitely conquered at one stage. We'll return to the idea of colonies later.

Orichalcum

It really exists. That is, Plato wrote of a metal, orichalc, "in those days the most valuable metal except gold." Beyond that, Plato ascribes no properties to the metal. It certainly didn't animate machines or move mountains, as later happens in Fate of Atlantis. Incidentally, the term is not an invention of Plato: other Greek authors of the period used it. It is not known for sure what the original meaning was, although the most common conclusion is that it refers to a gold-copper alloy.

Colossus

Now this is interesting. According to Hermocrates, "As the waters rose around their city, the Kings of Atlantis... sought to hold off fate. Knowing mortal men would never rule the sea, they planned a huge Colossus... which would make them like the Gods themselves." Having gone over the original myth ourselves, the question is: why bother? The Atlanteans were divine beings, ie gods, to begin with. True, they had degenerated into mortal beings, but as we've seen above the Atlanteans themselves didn't know anything was amiss.

Then again, we don't know what Zeus' punishment was to be. Maybe after the punishment the Atlanteans realised their true condition, and resolved to return themselves to godhood. More importantly, Barwood and Falstein are playing on the popular misconception of the Atlantis myth.

There is a conception among people that there are, or should be, limits to knowledge. That some things are better left unknown. This antiscientific, obscurantist view has come to be identified with a version of the Atlantis myth. Here are a group of people, we see, who seem to have reached the pinnacle of civilisation. Bright, wealthy, knowledgeable, wise and generally brilliant. But they flew too high, delved too deep, built the tower of Babel, dared to become gods. And were destroyed for their arrogance. The moral of this story seems to be that we should be glad there are limits to human power, because we're not responsible enough to be entrusted with the keys to the universe, so to speak. We are as babes, stumbling about in a hostile universe.

The colossus is thus an invention of Barwood and Falstein, serving both as a demonstration of the Atlanteans' hubris and later, in Atlantis, to give a more direct demonstration of their corruption, via the horribly mutilated skeletons of the "many freaks of nature."

Iceland

The former site of the Jastro expedition, a Bjorn Heimdall is now manning the site, looking for evidence of... well, something. In truth, there's not much linking Iceland to Atlantis. Possibly some authors have nominated it as a colony. In a more general new-age interconnectedness sense, the Greeks sailed to Iceland and called it Hyperborea (while never putting foot to shore - mysterious), while the tale of Atlantis was told by Plato, a Greek, which is just too much of a coincidence to be a coincidence.

Also, Iceland is often mentioned in connection with aliens, and it's an article of faith amongst your Atlantis believer that aliens are involved somewhere in the tale of the lost city, so... it's easy enough to tease out a connection if you want to. Bjorn Heimdall certainly wants to. He's a good satire of your average Atlantis crackpot: "They were stopped by a force field! Put here by beings not of this earth!", and Indy's reaction is pretty appropriate: "Hmmm... that's fascinating, doctor..." Now isn't it time for your nap?

Tikal

To start with, Tikal is a real place. It's one of a number of abandoned Mayan cities, such as Palenque, Uxmal, Chichén Itzá, and Mayapan, and perhaps the most famous. When European explorers arrived in Central America in the early 16th century, they found many such cities abandoned or sparsely populated. Warfare and famine had taken their toll, and Tikal in particular had been empty for half a millennium.

The Atlantis connection isn't hard to find. For example, Mayans = Aliens = Atlantis. More seriously, Central America is one of those areas routinely considered to have held Atlantean outposts. Mitchell-Hedges, a turn of the century archaeologist, thought there was a likely outpost of Atlantis in the Bay Islands, off the coast of Honduras. Mitchell-Hedges is probably more famous, however, for a crystal skull his daughter claimed to have discovered in British Honduras in the mid 1920's. And no, you’re not hallucinating, there was something about a crystal skull in the latest Indiana Jones movie. See, everything connects!

You don't meet Mitchell-Hedges in Fate of Atlantis. Rather, Tikal is watched over by Professor Charles Sternhart, who is possibly based on Mitchell-Hedges. Sternhart is convinced the Tikal temple was built by Atlanteans.

He also introduces us to another idea that's familiar currency amongst the Atlantis writers: there are two kinds of colonies. One, the colonies established by Atlantis when it was a mighty power. Two, the colonies established by Atlanteans fleeing the destruction of their land. Tikal, says Sternhart, is one of the latter.

Later on you get to go inside the temple, where you find an elephant statue, the tomb of an Atlantean King, and a bead of orichalcum. All of these are drawn from Plato, although the idea of orichalcum being dispensed in tiny circular beads is probably an invention of Barwood and Falstein.

Crete

What has Atlantis got to do with Crete? Not much, at least with the tale told by Plato. Atlantis may have controlled land up to Italy and Egypt, but whether it ever conquered Crete is not told. Given the location of Crete (due south of Athens) it doesn't seem likely.

In fact there is plenty to connect Crete with Atlantis, via a historical explanation of the myth. Indeed, Crete may well be Atlantis. But we'll get to that later.

For now, if Crete doesn't feature much in the tale of Atlantis, it is an enormous presence in Greek mythology. From an intriguing blend of myth and fact, Barwood and Falstein draw together a large part of the game.

The tale begins (where else?) with Zeus, ruler of the pantheon of Greek Gods. One day Zeus spied a young girl called Europa, gathering flowers by the seashore. Europa was the daughter of a Phoenician king, and Zeus instantly fell in love with her. He appeared to her as a beautiful chestnut-colored bull, and enticed Europa to climb on his back. He then sped away to the island of Crete. There, Europa bore him three sons: Minos, Rhadamanthus and Sarpedon; and each of them became kings.

King Minos, in particular, was a just and powerful king, dwelling in a palace built near the city of Knossos. There seems to be some historical basis for the tales around King Minos: there is certainly a historical basis to the account of the splendour of Crete. In those days (the second millennium BC), Knossos was the centre of the highly developed Minoan culture, as named after King Minos.

Most of what we know about Knossos comes from the work of British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans. Starting in 1900, Evans unearthed the Palace of Knossos, which he associated with King Minos. He and later archaeologists determined that the original palace was destroyed sometime in 1700 BC, before being rebuilt to a far more elaborate scale. The final destruction came at the hands of the Mycenaeans, who overran Knossos and Minoan Crete around 1400 BC.

Work continued at the site for a long time, finally concluding in early 1935. Discovered during this period were three thousand stone tablets, containing scripts of two languages dubbed Linear A and Linear B. Linear A has since been deciphered; Linear B is still a mystery.

But note the date: early 1935. Fate of Atlantis takes place after Indy finds the Holy Grail, and the manual dates the adventure to 1939. When Indy arrives in Crete his first task is to search an old dig site for the Moonstone. It seems clear, and it becomes clear when you compare the artwork with actual photographs of the Palace, that Indy is searching through Evans' dig site. Thus there is historical plausibility: it is entirely possible, in the time period set by the game, that someone (Indy, perhaps?) could have searched the ruins of Knossos for a stone disc.

Eventually Indy finds the disc, and the next section of the game opens up: exploring the Labyrinth. Now this is clearly myth, but it's not made up by Barwood and Falstein: according to Greek legend, there really was a labyrinth under the city of Knossos. The legend also stated that the layout of the Labyrinth was based on a mural on the floor of the Palace. The mural has been found; the Labyrinth has not.

Perhaps we should not expect to find the Labyrinth: after all, it is the home of the Minotaur, a creature of pure myth. One day Poseidon, Greek God of the sea and Zeus' brother, decided to send a snow-white bull to King Minos. However Minos refused to sacrifice the beast, angering Poseidon. In revenge, Poseidon made Pasiphaë (Minos' wife) fall in love with the bull (this all sounds like a cheesy soap opera, I know). There was nothing Minos could do, and soon Pasiphaë gave birth to the Minotaur, a grotesque beast with the body of a man and the head of a bull. Seeing the Minotaur, Minos ordered the architect and inventor Daedalus to build a labyrinth so intricate that escape from it would be impossible. Here the Minotaur was confined and fed young human victims Minos forced Athens to send to him. This slaughter was eventually ended thanks to the efforts of the Athenian hero Theseus, but it's a long story.

It's this labyrinth that Indy and Sophia find themselves exploring. Later on they even encounter a huge stone statue with the body of a man and the head of a bull. "For all I know it's the original Minotaur," Indy says.

Thera

Nowadays, a popular historical explanation of the story of Atlantis is that it was derived, in a roundabout fashion, from the fall of Minoan Crete. This possibility was first suggested by K.T. Frost in 1913, in an article titled 'Critias and Minoan Crete.' If we start by assuming the Solon story to be true (that is, an Egyptian priest did tell a relative of Plato the tale, or a similar tale to, Atlantis), then what possible powerful island civilisation and its destruction could the Egyptians have been referring to? Crete, perhaps: certainly there was contact between Egypt and Crete at the time of the fall of Minoan Crete. Of course, Plato did not have Crete in mind when he wrote the legend of Atlantis, and any search for correspondence between the and the land around Knossos is futile. It was just a convenient story that he latched onto for his own purposes.

The theory has some slight problems. For one, Crete is to the south of Greece, not the west. But to the Egyptians Crete was in the northwest, and the Greeks regarded the west as a place of fable and mystery, and this probably accounts for the displacement.

But a natural disaster overwhelmed Atlantis. What natural disaster struck Crete? At the time of Frost's writings, no such disaster was known to historians.

The final piece of the puzzle was supplied by Professor Marinatos. In 1939 (again, note that date!) he drew attention to a volcanic explosion which overwhelmed the island of Santorini, or Thera as it was known in antiquity. This was a big explosion. The largest eruption of modern times is usually given as Krakatoa, which was heard over three thousand miles away. But the crater at Thera is four times as big. And Knossos is less than eighty miles south of Thera, directly visible over the sea.

The modern picture is this: following several years of intense earthquakes (large eruptions are usually preceded by numerous tremors), Thera detonated, the greater part of the island being blown into the sea. Massive tidal waves arose, speeding south to Knossos where they crashed against the shore, causing widespread destruction. After the water came the ash, falling in enormous quantities, covering the ground in layers thicker than 20cm. There is actual evidence for such a fall, most of which would have been concentrated on Crete by the prevailing winds of the area. Such a fall would destroy vegetation and make the land uninhabitable for decades. Following such a knockout punch, it's not much of a surprise that Knossos later fell to the Mycenaeans.

It's here that things get really interesting. In the course of his work on Santorini during the 1930’s, a Professor Marinatos uncovered clear evidence of Minoan settlement. Now, in Fate of Atlantis, you don't get to visit Thera at all if you play through on the Team path. If you take the Fists path, you visit Thera and there encounter a shady seaboat captain. And if you take the Wits path, you come across a less-than-helpful port authority. Despite a slightly crusty nature, he seems to know a lot about Thera. When Indy tells him this is a nice island, he says, "The famous old volcano; the awful explosion; the end of civilisation... yes, very nice indeed."

Later on a puzzle forces you to find an artefact to interest the port authority. Indy comes across a carved stone sign, covered in ancient markings. He takes it to the port authority, and lo and behold, the sign is covered in Minoan hieroglyphics, and the port authority is completely fluent.

Just where did Professor Marinatos uncover the evidence of Minoan settlement, evidence he published in 1939? And who helped him? A certain fedora-hat-wearing stranger, perhaps?

Atlantis

So the modern theory, as outlined above, is that the explosion on Thera decimated Minoan Crete, the Egyptians knew about this, and the tale filtered via Solon to the ears of Plato. This also explains why the tale of Atlantis isn't known to any other Greek writers of the time.

There are just a few loose ends left to tie up, relating to the design Barwood and Falstein drew up for Atlantis itself. The basic structure is that outlined by Plato himself - concentric circles separated by canals. More interesting is the Atlantean artwork, which has clearly been influenced by the dominant presence of the bull in both Atlantean and Greek mythology. A couple of elephant statues turn up, which is derived from Plato (the Atlanteans apparently had many elephants). Crabs: the city Indy and Sophia explore is full of them, but no specific reference turns up in Plato, although he does note there was plenty of food for "all creatures whose habitat is marsh, swamp and river, mountain or plain." Most of the Atlantis design seems to have been dictated by the story developed by Barwood and Falstein, and so the rooms are muddy and decayed, everything feels wrong, and ancient, wrecked skeletons litter the floor.

"This isn't exactly how I imagined the splendour of the Lost City," says Sophia uncertainly, and it's exactly that effect that Fate of Atlantis succeeds in evoking, at the same time being truer to the real myth than thousands of books have gotten.